Article

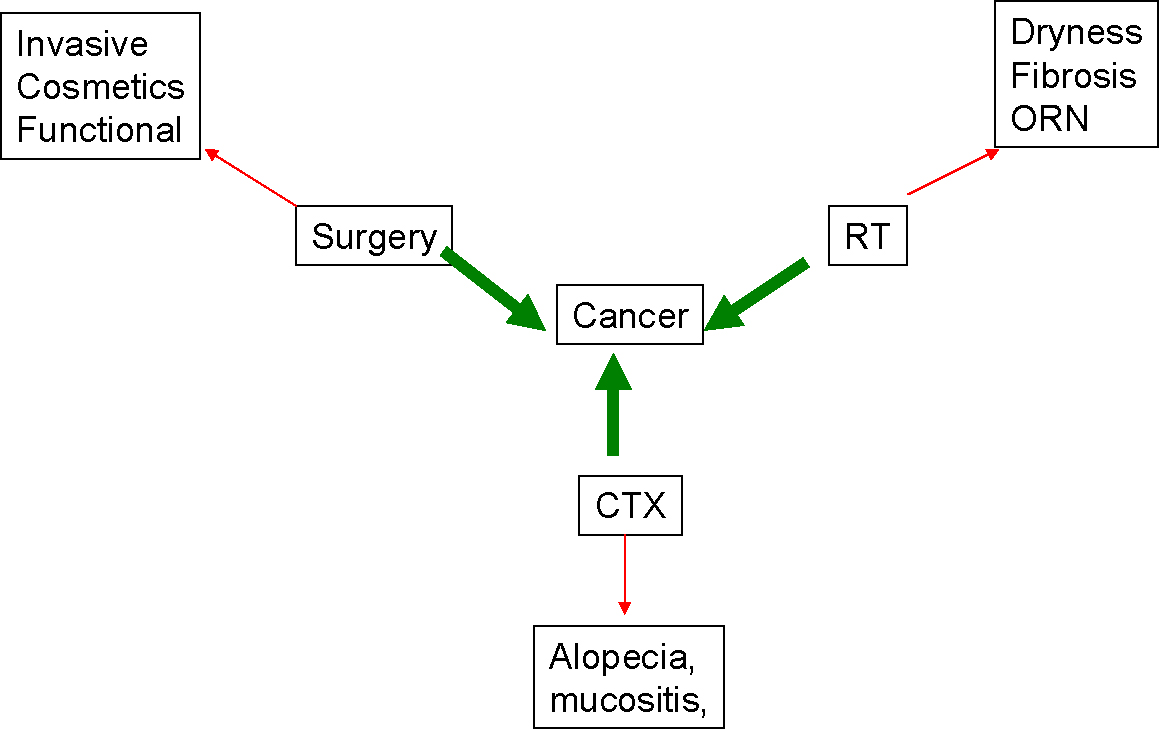

Oral cancer and its management are associated with tremendous physical, emotional and psychosocial disruption, as discussed in Article 8. This affects patients' ‘quality of life’ (QoL) and impacts not only on them but also their family, carers and others. Thus, while the aims of cancer treatment must ideally be to remove or destroy the tumour entirely, the outcome is a balance between positive results (eg survival; freedom from tumour) and adverse effects (eg psychological sequelae; treatment side-effects) (Figure 1). Survival rates are improving so more patients are having to live with the adverse effects of having cancer and its treatment.

Cure means there is no evidence of cancer following treatment, but since in some cases cancer recurs later, ‘remission’ is a more appropriate term. In some cases, treatment aims rather to control the cancer so that it progresses less rapidly. In other cases, where the cancer is far advanced or the patient has such co-morbidities that treatment is limited, it may be palliative, aiming to ease symptoms only – for example, reducing tumour size (debulking) to ease pain or difficulty swallowing.

Thus, as well as the conventional cancer quality outcomes assessments of survival, morbidity and years free of disease, QoL assessment is considered an essential component of modern healthcare for the oral cancer patient.

Definitions of quality of life

The term quality of life (QoL) is used in a wide range of contexts, and should not be confused with the concept of standard of living, which is based primarily on income or wealth. QoL is a broad concept encompassing many aspects, not only wealth, employment and housing, but also physical and mental health, recreation, leisure and social belonging. WHO has defined QoL as ‘Individuals’ perceptions of their position in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns’.

In healthcare, QoL is often seen in terms of how it is negatively affected, on an individual level, in a debilitating illness.

Health-related quality of life

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a subset of QoL, involving:

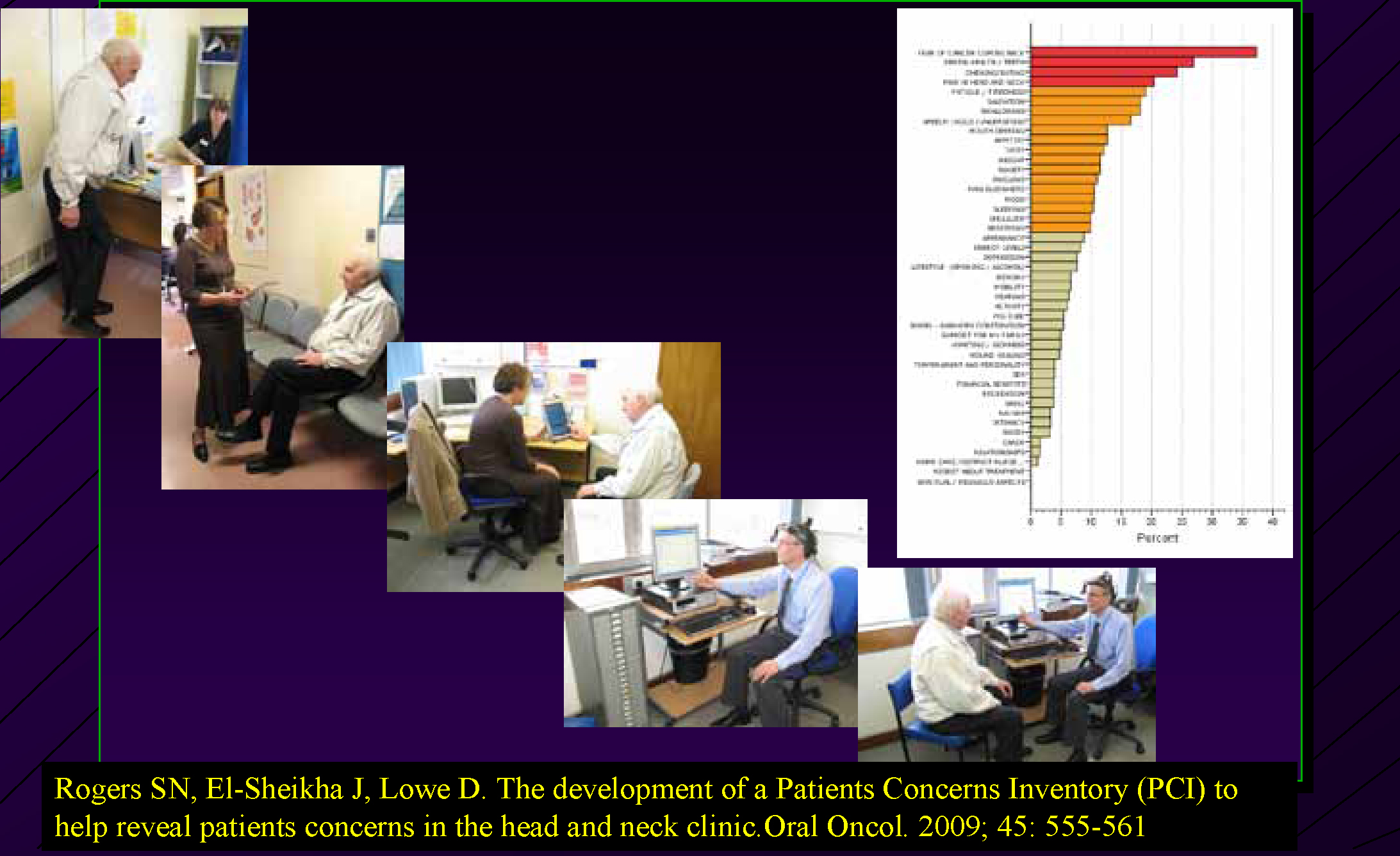

HRQoL can be assessed by interview or patient-completed questionnaires. HRQoL questionnaires are available on computer systems, have been validated, and can be used not only to record outcomes, but also to inform the treatment decision process, help change and shape clinical practice, and for screening and intervention following treatment. The development of a Patients Concerns Inventory (PCI) has enhanced HCPs’ ability to recognize unmet needs and concerns.

Key HRQoL concerns

Not surprisingly, most of the concerns of patients with oral cancer relate to orofacial issues. Many complaints from patients who have cancer elsewhere in the head and neck also relate to oral problems.

A diagnosis of oral cancer, like any cancer diagnosis, is almost invariably accompanied by uncertainty, trepidation and fear. From the outset, patients may be aware that they almost certainly face at least some difficulties in eating, chewing, drinking, breathing, speaking, as well as possible changes in appearance. Few patients can completely conceal the effects of treatment because of the obviously visible nature of their condition and treatment outcomes, especially obvious functional difficulties affecting speech and mastication. Head and neck cancer is probably more emotionally traumatic than any other cancer, with very specific and vast needs beyond those of most other cancer victims. Psychosocial dysfunction is thus virtually invariably to be anticipated, and interventions needed (Article 8).

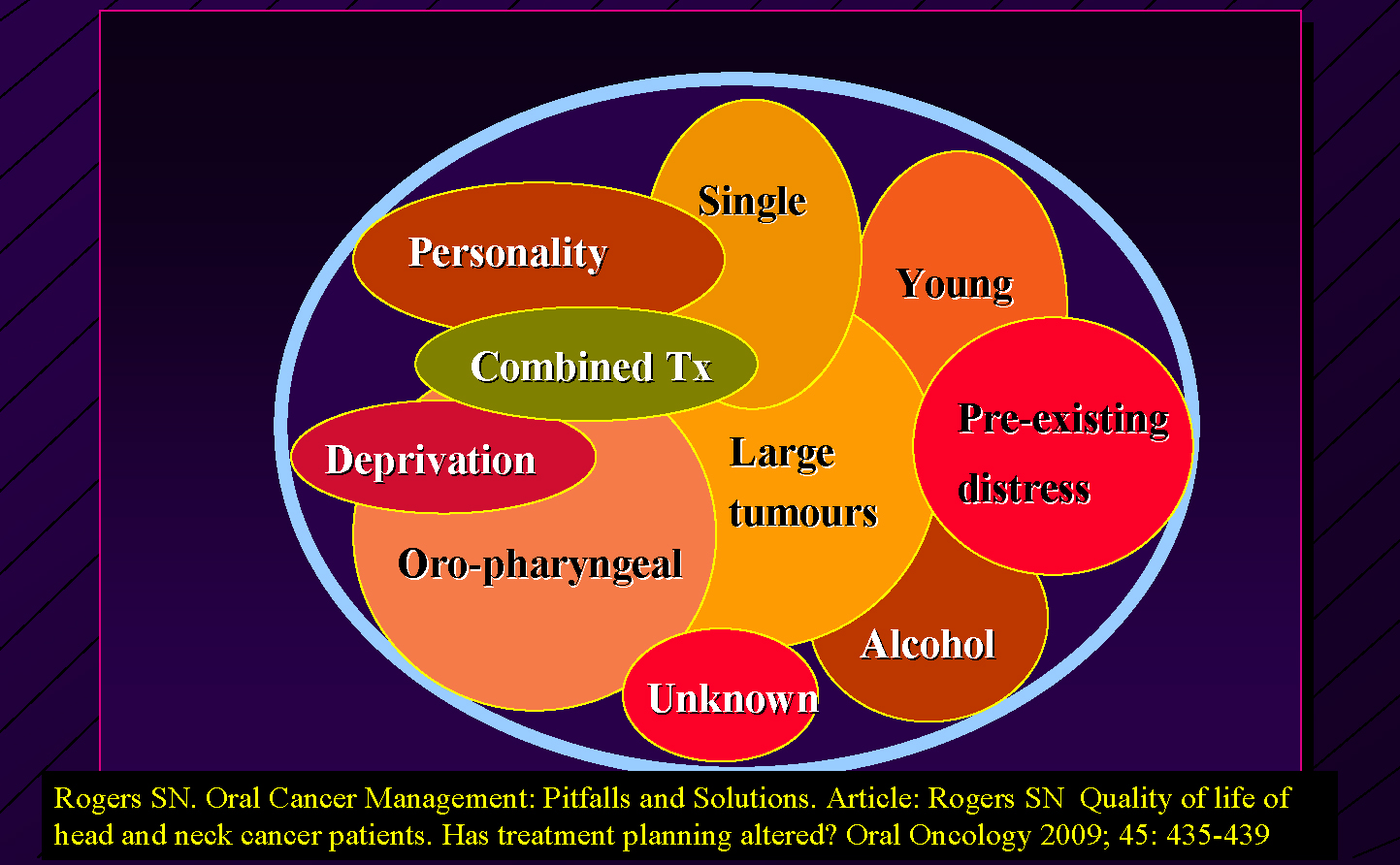

Socio-economic factors and cancer stage are especially important factors behind patients' concerns. Patients of older age, lower annual family income, more advanced cancer stage and flap reconstruction tend to have significantly worse physical concerns, and those with lower annual family income, unemployment and more advanced cancer stage often report significantly worse mental concerns.

The main concerns include carer burden and support, coping, dental status, disfigurement, emotional aspects, fear of recurrence, finance, function, information, intimacy, oral rehabilitation, PEG (per-endoscopic gastrostomy) feeding, personality, sociodemographic, speech, swallowing, shoulder movement, trismus, and xerostomia. In HRQol evaluation, researchers have found that four items are usually found to be the most important to patients;

Early identification and referral are essential for improved QoL. The main factors affecting HRQoL are radiotherapy, advanced clinical stage, socioeconomic status, and patient age (Figure 2).

In the management of oral cancer, HRQoL outcomes seem most favourable after surgical treatment of oral cancer. At one year after surgery for tongue cancer, the appearance, activity, speech, swallowing, shoulder function, salivary, and taste domain scores tend to have fallen from pre-operative scores, but the pain, anxiety, and mood scores are usually significantly better by one year after surgery. The overall QoL also increases greatly by 1 year after surgery but does not reach pretreatment levels. Nevertheless, at 1 year following primary surgery for oral cancer, HRQoL is generally good, very good, or outstanding and tends to be maintained long-term.

Radiotherapy (RT) is indicated in specific situations, but it can be difficult on an individual patient basis to decide on the benefit adjuvant radiotherapy might give in improving survival. What is clear is that patients who have RT generally have a significantly worse HRQoL outcome (mainly due to post-radiation dry mouth and trismus). Among cancer patients receiving RT, HRQoL tends to decrease over time, and oral symptoms increase. For patients receiving chemotherapy, QoL tends not to change during the chemotherapy cycle.

Despite encouraging treatment outcomes, a very common concern is fear of the cancer returning.

The dental multidisciplinary team

Specialists at the regional cancer centre (tertiary healthcare) have a key role in decision-making, delivery of primary treatment, and management of further disease, but primary healthcare professionals (HCPs) have a crucial role in long-term care and support (including psychological).

Access to dental care can be problematic and it is important for a cancer patient to be able to be able to access an urgent appointment if required. Patients should have had a dental assessment at the time of their treatment planning. Teeth of dubious prognosis should have been extracted before RT, since patients requiring extractions are at risk of developing osteoradionecrosis (Article 17). If an extraction is required following radiotherapy, it is best to consult the regional cancer centre. Regular dental reviews close to the patient's home afford opportunities for screening and reinforcing lifestyle issues (smoking cessation and alcohol reduction) and reduce the inconvenience of travel to the regional cancer centre. Dental and oral health must be maintained at a high level. Chewing is a key concern to patients and the dentition is also important for appearance, self-esteem and psychosocial well-being. Oral rehabilitation needs to be in keeping with the patient's motivation and needs. If an extraction is required, it is best to consult the regional cancer centre. Guidance concerning dietary intake and caries is important, as is regular use of fluoride preparations, mouth wetting agents (saliva substitutes) for those patients with a dry mouth and care by the dental hygienist (Figure 3).

Patients surviving oral cancer have many different individual needs to be met, to ensure quality of life and this is achieved by a holistic multidisciplinary approach.