Article

The transitory function of provisional crowns means that these restorations are frequently fabricated directly in the mouth using comparatively inexpensive procedures.1

Many operators will use an alginate or silicone impression of the tooth to be prepared to produce a provisional crown that duplicates the form of the existing tooth.2 This matrix technique has proved popular, especially when a silicone impression is taken. Such materials enable the operator to retain a dimensionally stable index of the prepared tooth form, during the inter-appointment period, in case of failures. However, some situations will require a modification of this approach. These are, inter alia:

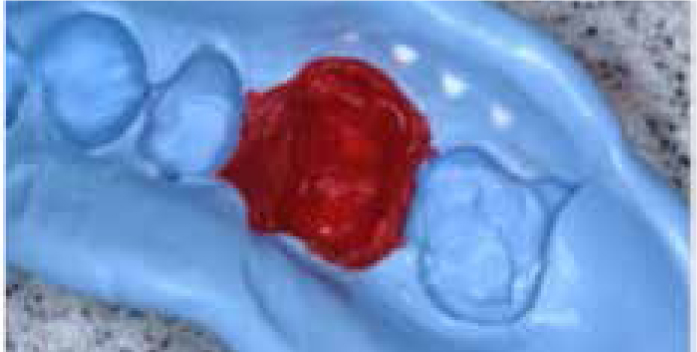

In such situations, the clinician has little to go on to help reproduce the external contours of the damaged tooth. Consequently, the shape of the tooth must first be improved before construction of a matrix (Figure 1).

We present a simple procedure that has proved satisfactory in overcoming some of the challenges presented.

This procedure requires no special equipment, is relatively simple and is particularly suited for the construction of provisionals when the pre-operative external contour of the tooth is unknown; due to lost restorations, loss of tooth structure, or when a pre-operative matrix is unavailable.

Discussion

Red ribbon wax was used in this technique tip, since it is easy to handle, inexpensive and widely available. This does not imply that other materials cannot be considered.

Resin composite and poly-ethyl acrylic are two such materials that can also be used to similar effect. While the former is surely available to almost all practitioners, the increased cost, together with the need to employ effective moisture control techniques, represent disadvantages when this material is compared to red ribbon wax.

Self-curing acrylics have a long track record for use as direct provisional restorations, however, their use has declined in recent years, owing to the popularity of alternatives such as Bis-acryl.1 Consequently, it seems reasonable to infer that not all practitioners will choose to stock self-cure acrylics in practice. As well as such issues with availability, poly-ethyl acrylics undergo an exothermic setting reaction and the potential trauma to the pulp cannot be ignored. A further disadvantage is that acrylic requires significant time to set fully as compared with the wax technique.