References

An audit on the professional intervention of smoking

From Volume 44, Issue 8, September 2017 | Pages 781-786

Article

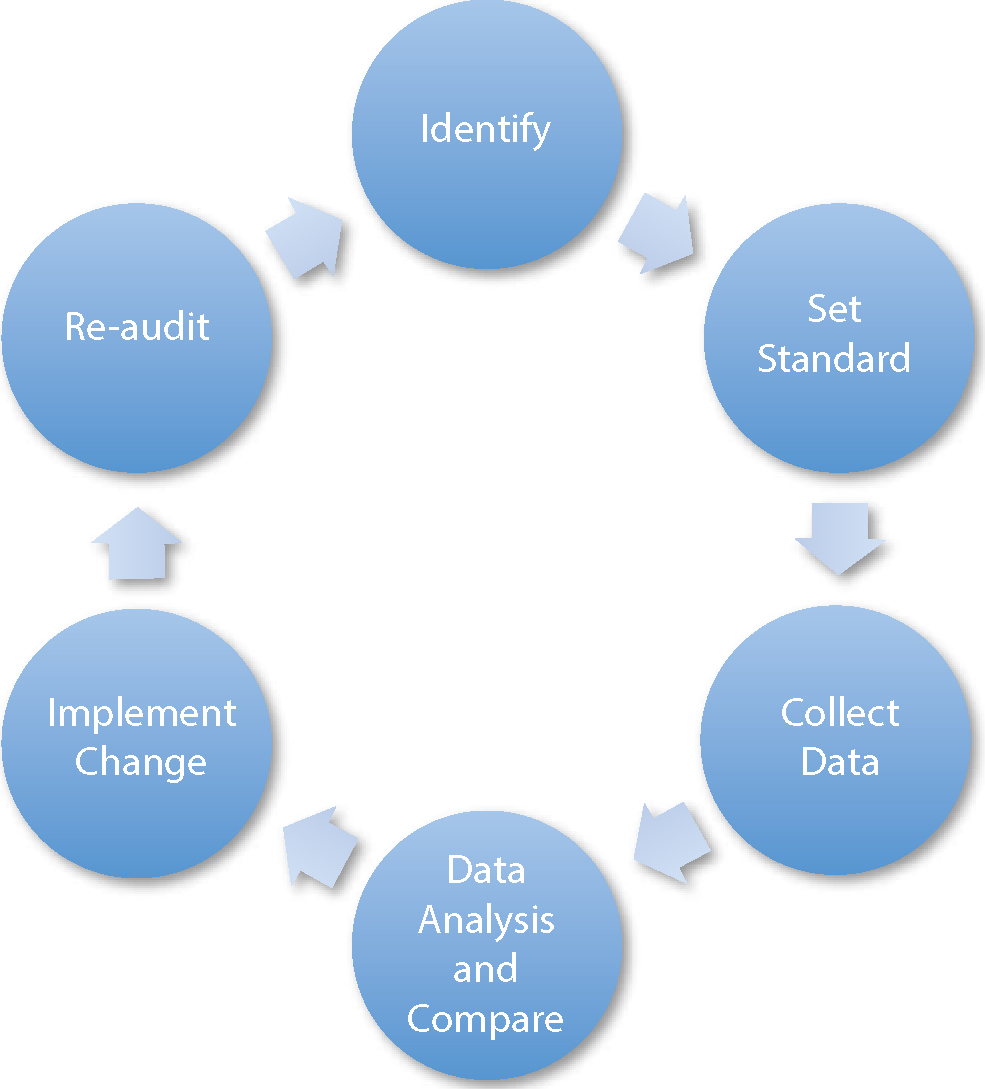

The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence defines a clinical audit as a quality improvement process that seeks to improve patient care and outcomes through systematic review of care and the implementation of change.

The different steps that make up the audit cycle are outlined in Figure 1.

This article will discuss an audit regarding the provision of professional intervention for smoking by dental practitioners outlining each of these steps.

Identification

As well as general health complications, risks of smoking to oral health are vast, including periodontal disease, poor post-operative wound healing, effect on dental implants, discoloration of teeth and restorations and halitosis.1 Perhaps the most significant and dangerous risk is oral cancer, where smokers are ten times more likely to suffer from oral cancer than people who have never smoked.2 It is important that the general dental practitioner is delivering information regarding smoking cessation as required and recommended.

This audit aimed to:

Setting standards

Guidance is provided and can be seen in ‘Delivering Better Oral Health (DBOH)’ by Public Health England.3 It is important to note that the guidance is based on a strong level of evidence. In summary, it recommends that ‘very brief advice’ (VBA) is given to patients. This consists of three elements:

It is significant to note that DBOH recommends that all patients should be asked about their smoking status at least once a year and all smokers should receive advice about the value of attending their local stop smoking services for specialized help. Those who are interested and motivated to stop should receive information about these services.

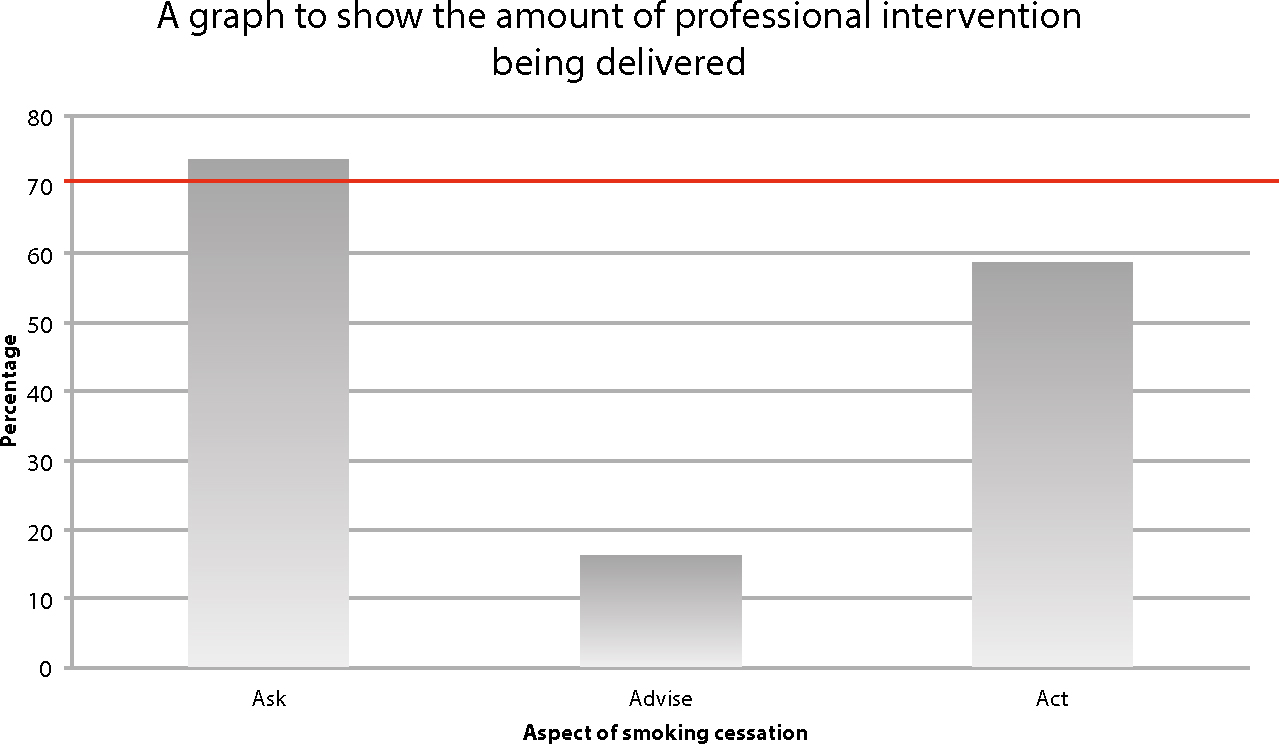

Taking into account that some patients have shorter recall intervals than a year for their oral health assessments and the reliability of data collection method (as explained later), the standard set for providing professional intervention was 70% for the first cycle. This was deemed to be realistic and appropriate.

Collecting data

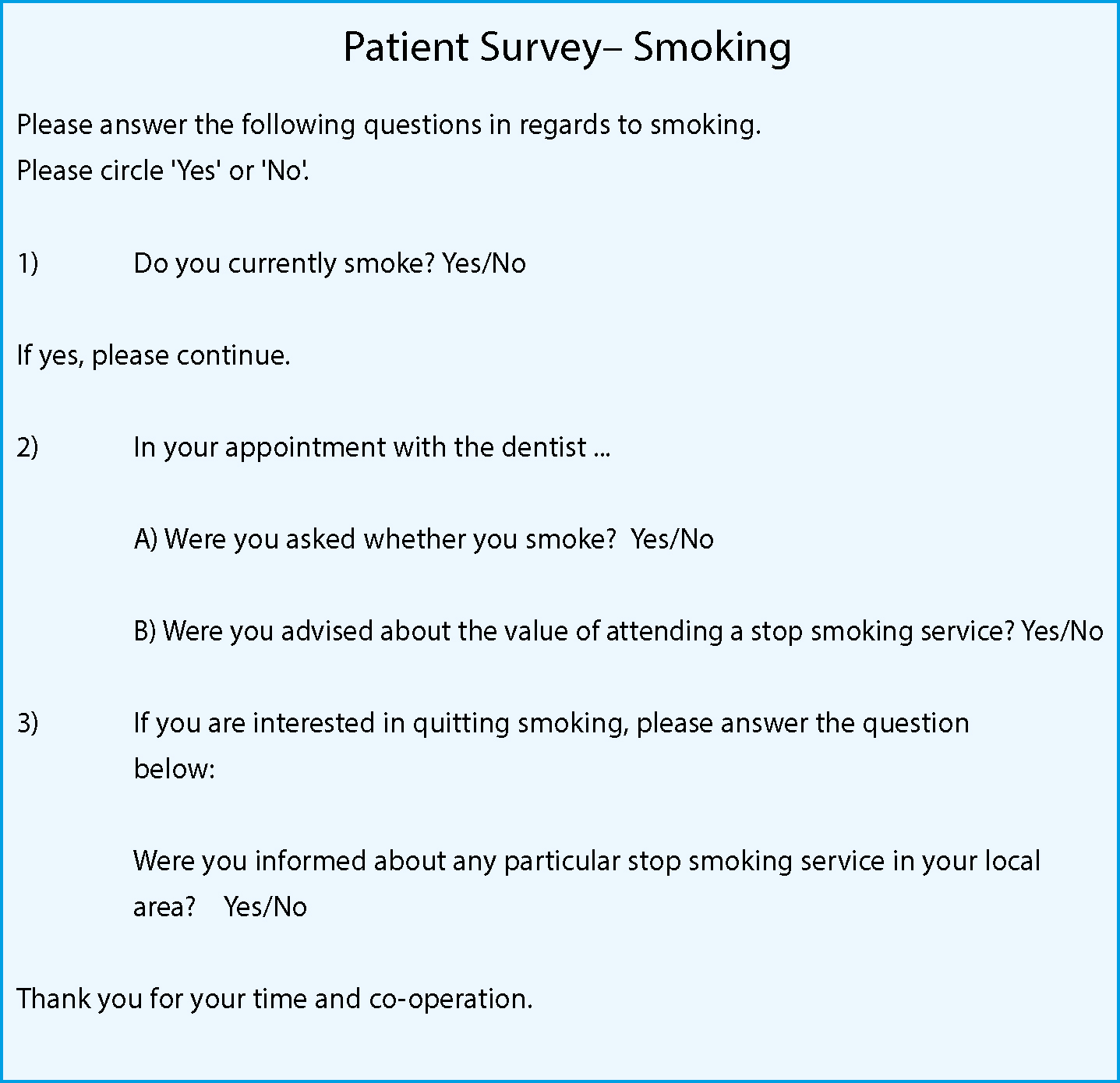

This was to be a prospective audit, meaning that the data collection technique could be specifically designed to meet the needs of the audit. The data capture sheet is shown in Figure 2.

The questionnaire was given to all new and current patients after examinations at reception. It measured the ‘Ask, Advise and Act’ as described before. It was made as clear and objective as possible, maintained confidentiality and smoking status was easily identifiable. Each dentist at the practice was allocated a number which the receptionist placed at the top of the sheet.

By asking the patient, it eliminated unreliability in dental records and ensured that it was only measuring intervention that had been delivered and recalled by the patient (so presumably of good quality). However, disadvantageously, patients may not have listened to the dentist or correctly completed the questionnaire.

The benefits of utilizing the receptionists to collect data were that there was minimal impact on clinical time and appropriate patients (ie those having an oral health assessment) could be identified.

Four dentists were being audited, with a sample of 20 patient questionnaires for each. Non-smokers were not included in this 20. The resulting 80 results were deemed enough data for a reliable conclusion.

The exclusion criteria for the audit was that only current smokers aged 18 or above that were examined by dentists were used and the focus was only on smoking and not other forms of carcinogens, eg chewing paan.

A one-month timeframe was sufficient to collect all the data, as there was a large frequency of occurrence. An initial pilot audit confirmed this timeframe and the questionnaire (in regards to clarity and ease of use) was adequate.

Data analysis and compare

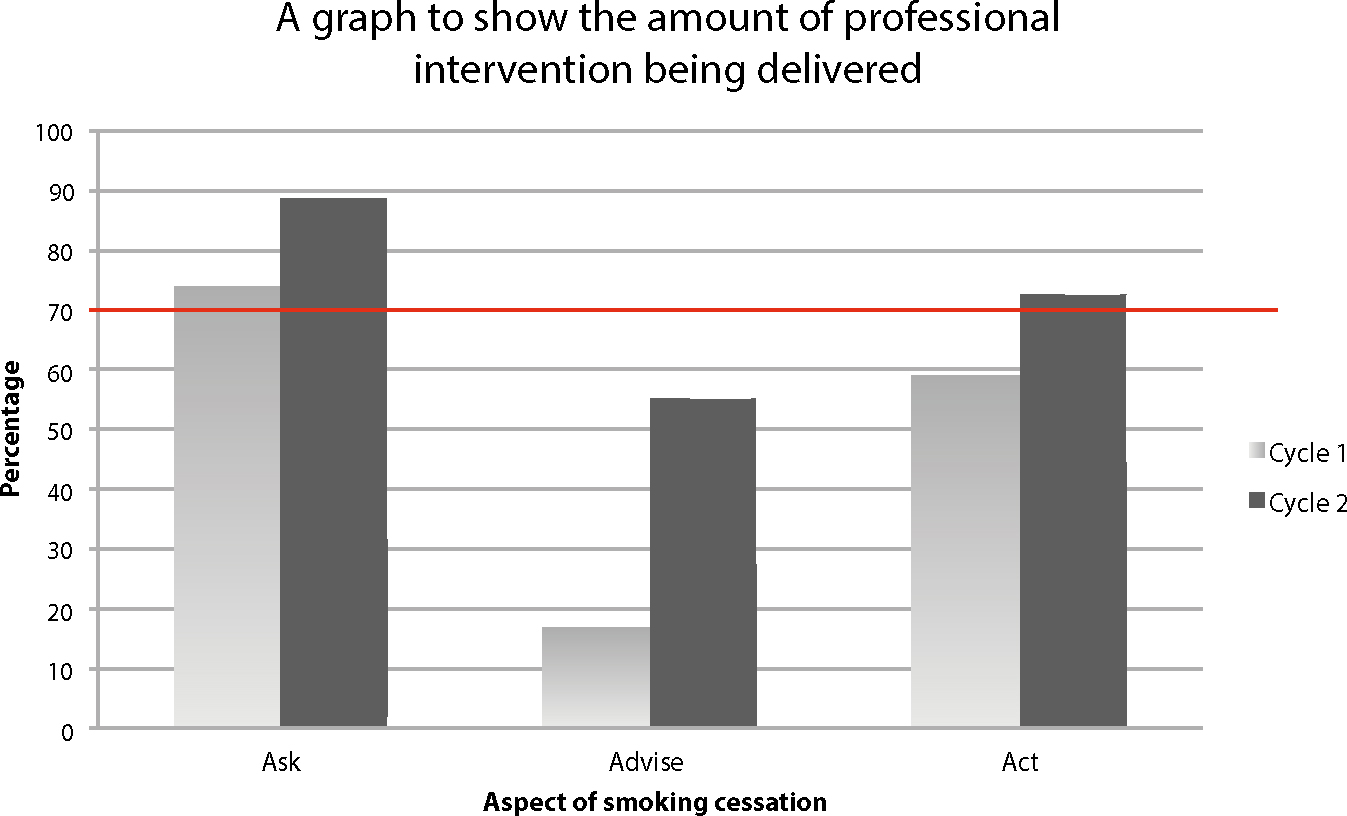

The results of cycle 1 are shown in Figure 3. The summary of the findings from cycle 1 was:

It is important to remember that for the ‘Act’ section, this was only taken into account if the patient was considering quitting smoking as otherwise it might not be necessary or appropriate to ‘act’, as explained before.

After a team meeting to discuss the findings and reasons for the shortcomings, it became apparent that further education regarding professional intervention for smoking and clarification of a specific smoking cessation service that patients could be signposted to was required.

Another patient questionnaire was also given to identify how patients would like to be informed about smoking cessation. The main requested ways were posters, written information, verbally and online.

Changes implemented

The main change was team education regarding DBOH, which took place at further team meetings. The whole dental team was encouraged to use the ‘VBA’ approach. A new partnership with a local pharmacy that provided smoking cessation services meant that the dentists felt comfortable in knowing where they could signpost patients.

In response to patient feedback, a take-away patient leaflet was made that included information about risks of smoking, information regarding the benefits of attending smoking cessation services, including the local pharmacy, and a link to the NHS online smoking cessation website. Posters were also placed in the waiting room.

Re-audit

To eliminate bias, the second cycle, like the first, was carried out without the dentists' knowledge. It was carried out a month after all changes were implemented in order to ensure sufficient delay to ascertain how the changes truly affected the dentists' daily behaviours.

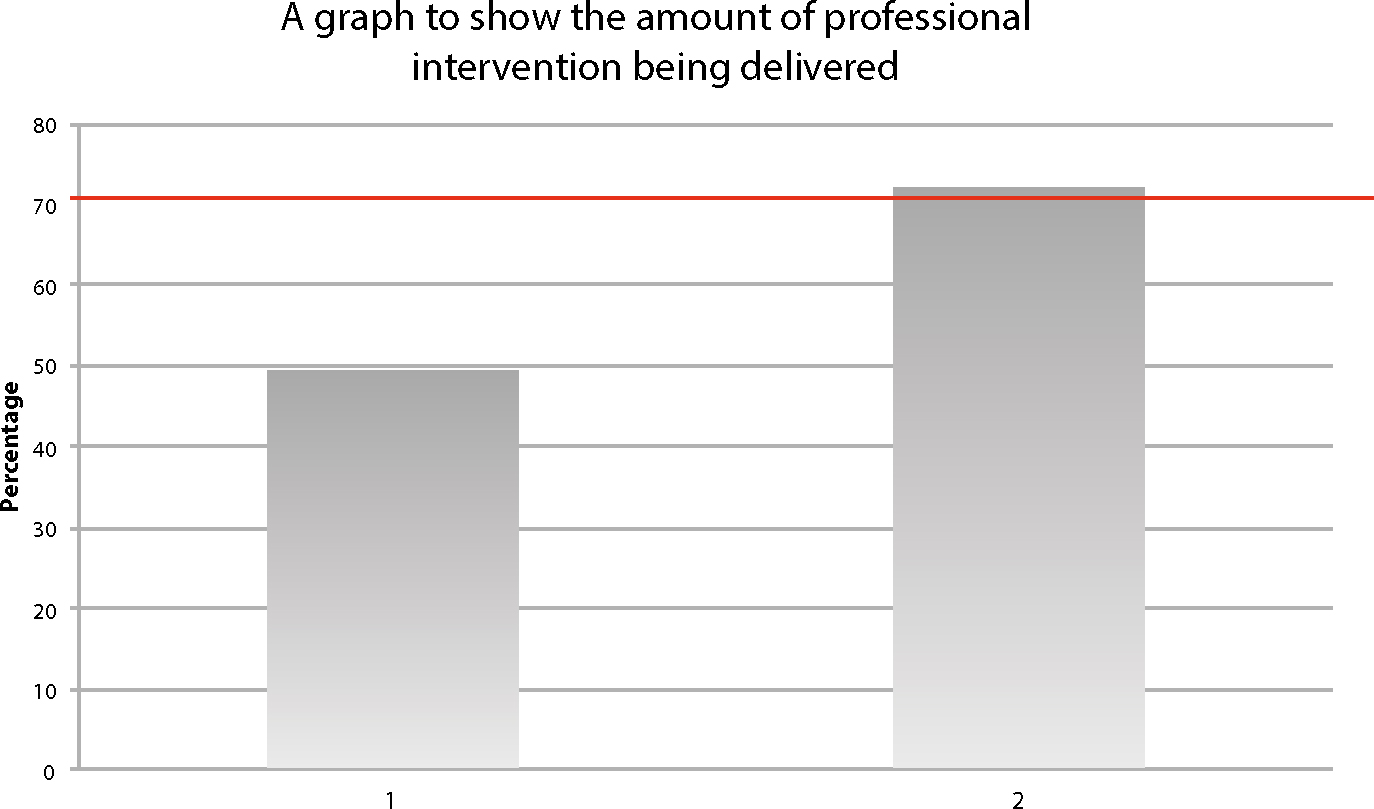

In the second cycle, a large increase of all the aspects of professional intervention, with an overall 23% improvement, was seen. The ‘advice’ was still below the set standard. These are shown in Figures 4 and 5.

Actions implemented after this cycle included further education of the dental team regarding the required intervention, and putting up ‘VBA’ posters as a reminder to dentists. A new practice policy was produced, providing information about the importance of smoking cessation, how to deliver it, where to signpost patients, where to get further information and the Smoking Cessation Lead. This was available for all to refer to and, most importantly, was to be included in the induction for all new staff; therefore, ensuring continual quality of care. For the next audit cycle, a standard of 80% was to be set.

Conclusion

This is a simple and effective audit that can easily be reproduced by dental practitioners. Changes include education of the dental team, putting up posters, giving patient leaflets, liaising with local smoking cessation services and introducing/updating the practice policy. There are many potential positive outcomes, including improved professional intervention delivery at the practice, higher standards of patient care and promoting prevention, higher standards of oral health, improved patient satisfaction, continual development of dental professionals, building partnerships with local smoking cessation services and highlighting the importance of auditing to the dental team.