Article

The management of tooth wear (TW) may often present a dilemma to the clinician. The clinical decision-making process between monitoring and active management can be difficult. Thorough history-taking and clinical assessment are essential parts of gathering sufficient information to allow the clinician and the patient to make these treatment decisions.

Uncontrolled tooth wear can lead to poor aesthetics, dentine hypersensitivity and functional problems, ultimately resulting in a reduced quality of life. Significant tooth structure loss can also lead to difficulties with any potential rehabilitation.1 Patients often only become aware of their TW when the appearance of their teeth begins to deteriorate or they become symptomatic. Enamel may appear thin or discoloured, begin to fracture and the teeth may appear shorter.2 Exposure of dentine can lead to transient pain in response to chemical, thermal, tactile or osmotic stimuli. This is commonly known as dentine hypersensitivity and may occur following loss of enamel with dentinal exposure secondary to tooth wear.3 This pain can often be unsettling for the patient and may lead to limitation of the types of food or beverage ingested.

Loss of tooth structure can have many restorative implications. The need to conserve tooth structure, in particular enamel, remains vital to the predictability of adhesive restorations which are indicated, where possible, to avoid removal of more tooth structure, as is required with conventional crown and bridge work.4 Further restorative difficulties can be encountered as TW causes loss of interocclusal space, thereby leaving limited space for the restorative material.

Uncontrolled tooth wear may ultimately result in decreased quality of life, affecting patients' satisfaction with their dentition, in particular; aesthetics, oral comfort and/or mastication.5 Correct diagnosis is therefore critical for successful management of TW. The predominant aetiology should be determined and the patient concerns identified.6 Although the rehabilitation of worn teeth is common clinical practice, there appears to be a stark absence of documented outcomes.

It has been identified in numerous reviews that there is no strong published evidence on management strategies.6,7 To date, most recommendations are based on published, evidence-based, expert opinion or observational studies, with a lack of high quality research supporting individual restorative measures for the replacement of tooth tissue.7

The decision to treat arises when the patient's needs, severity of the wear and potential for progression are of concern. There is a lack of evidence to suggest merely the presence of TW will predictably lead to severe wear.6 In the absence of aesthetic or functional issues, monitoring of the TW and preventive advice, including diet counselling, may be preferable.8,9

The preservation of tooth structure is critical. In cases of intrinsic erosion, prevention of further exposure to the damaging gastric contents is of paramount importance.10 The management strategy should be centred around medical management, and psychiatric evaluation if eating disorders are suspected.11 Parafunctional habits may exert highly destructive forces and are difficult to prevent in comparison to erosive wear.12 Despite prevention being the foundation for successful management, there is a lack of high quality evidence about the clinical effectiveness of most preventive measures.13

Indications for fixed management of tooth wear

Generalized/localized tooth wear in dentate patients with associated:

Contra-indications for fixed management of tooth wear

Contra-indications include:

Aims of fixed management of tooth wear

Restorative management of tooth wear may be necessary in order to achieve the aims of restoring the appearance, function and/or speech of patients with worn dentitions, conserving remaining tooth structure and reducing sensitivity or pain associated with worn teeth. This may be by means of fixed, removable or a combined fixed and removable restorative approach. Disadvantages of restorative treatment revolve around the patient entering the restorative maintenance cycle, thus rendering both the restorations and the teeth susceptible to fracture or even failure. The consequences of failures and their subsequent management must all be taken into consideration prior to embarking on a restorative management strategy.

Whenever prosthodontic rehabilitation is considered, the main determinants of successful treatment planning are restorative material properties, biomechanical factors and biological factors.

Preliminary investigations

The initial investigations should involve thorough assessment of the patient in order to identify the cause of wear and comprehensively assess the current clinical dilemma resulting from such wear. The relevant aesthetic, restorative, periodontal and endodontic examinations should be carried out along with any necessary radiographic investigations. This should be accompanied with a set of mounted study casts.

On conclusion of the assessments, the clinician will be able to draw conclusions on the overall state of the dentition, the complexity of the problem, individual and general prognosis and potential treatment options available.

Diagnostic phase

Mounted study casts

A set of articulated study casts can be used to assess the overall dentition, occlusal relationship, contacts and interferences, and restorative space available. The mounted casts can also be used to assess the effect of changing occlusal contacts (trial equilibration), diagnostic repositioning of teeth14 and to create a diagnostic preview.

If it is determined that reconstruction is required, treatment should aim to restore the worn dentition to a determined occlusal vertical dimension needed to create space for restoration of lost tooth tissue, avoiding sound tooth destruction, whilst ensuring acceptable function and aesthetics. In most patients who are fully or mostly dentate, where restorations will be tooth borne, such changes are well tolerated. The occlusal vertical dimension should ideally be captured with a jaw registration at or close to the desired vertical dimension, which is then used to mount the casts. A diagnostic wax-up can be carried out at the desired vertical dimension. This diagnostic preview forms the foundation for future treatment and can be transferred to the patient in order to assess proposed vertical dimension whilst assessing aesthetics and function.

Occlusal splints

A hard heat-cured full coverage acrylic splint can be used in the diagnostic phase. The ideal splint should provide even contact along the retruded arc of closure, with anterior guidance on anterior teeth with posterior disclusion and canine guidance in lateral excursions with no interferences from the posterior dentition.15 They can provide the following benefits:

This is probably unnecessary, since proprioception makes tolerance highly likely when occlusal loads are directed through the periodontal ligament (PDL), as with fixed restorations;

Partial coverage splints should be avoided due to potential selective intrusion and extrusion of teeth. The resulting malocclusion can be difficult to correct and a potential source of medicolegal litigation.

Planning strategies

Management strategies will be influenced by the following factors that should all be considered during the planning phase:

Aetiology and pattern of tooth wear

The aetiology of tooth wear and wear resistance of restored and natural teeth should be considered. Although some aetiologies can be controlled, some may be beyond the control of the patient or the clinician. It is essential to establish whether the restored dentition is likely to be exposed to such causes of wear prior to making material choices. Behaviour under normal and excessive loads will have an influence on decision-making, especially in parafunctional patients. Given the complex nature of the oral environment, both mechanical and biological failures are possible. Biological failures have been shown to be primary or secondary (often following a mechanical failure), and are more probable.21 Laboratory-based trials have shown the wear resistance of gold and ceramic materials to be similar, whereas resin-based materials have demonstrated three to four times more material wear than gold or ceramics. In cases of high load conditions, traditionally, metal or metal-ceramic restorations have been recommended as the material of choice,6 however, under extreme conditions there is no material that is likely to last. Nevertheless, survival of the restorative material is of far less importance by way of comparison to survival of the tooth and the dentino-pulpal complex.13

Modern resin-based restorative materials have risen in popularity due to their use being less destructive to the remaining tooth tissue whilst serving the functional requirements, bringing into question traditional fixed prosthodontic approaches.9

Localized tooth wear

The vast majority of studies are centred around management of localized tooth wear. Huge variations in outcomes exist in the reported success and survival of direct and indirect restorations. There has been a gradual evolution in restorative methods when it comes to the management of TW. Traditional methods revolved around full coverage cast restorations. Rochette's introduction of a method for cementation of metal alloy castings to enamel without relying primarily on macromechanical resistance and retention resulted in significant advances within restorative dentistry.22 The adhesive techniques proposed allowed for a more conservative approach to be adopted, whereby individual cast-metal veneers cemented to the palatal surfaces of anterior maxillary teeth. Further advances in the physical properties of resin-based restorations have resulted in a further development of management techniques involving the sole use of composite resin-based restorations.

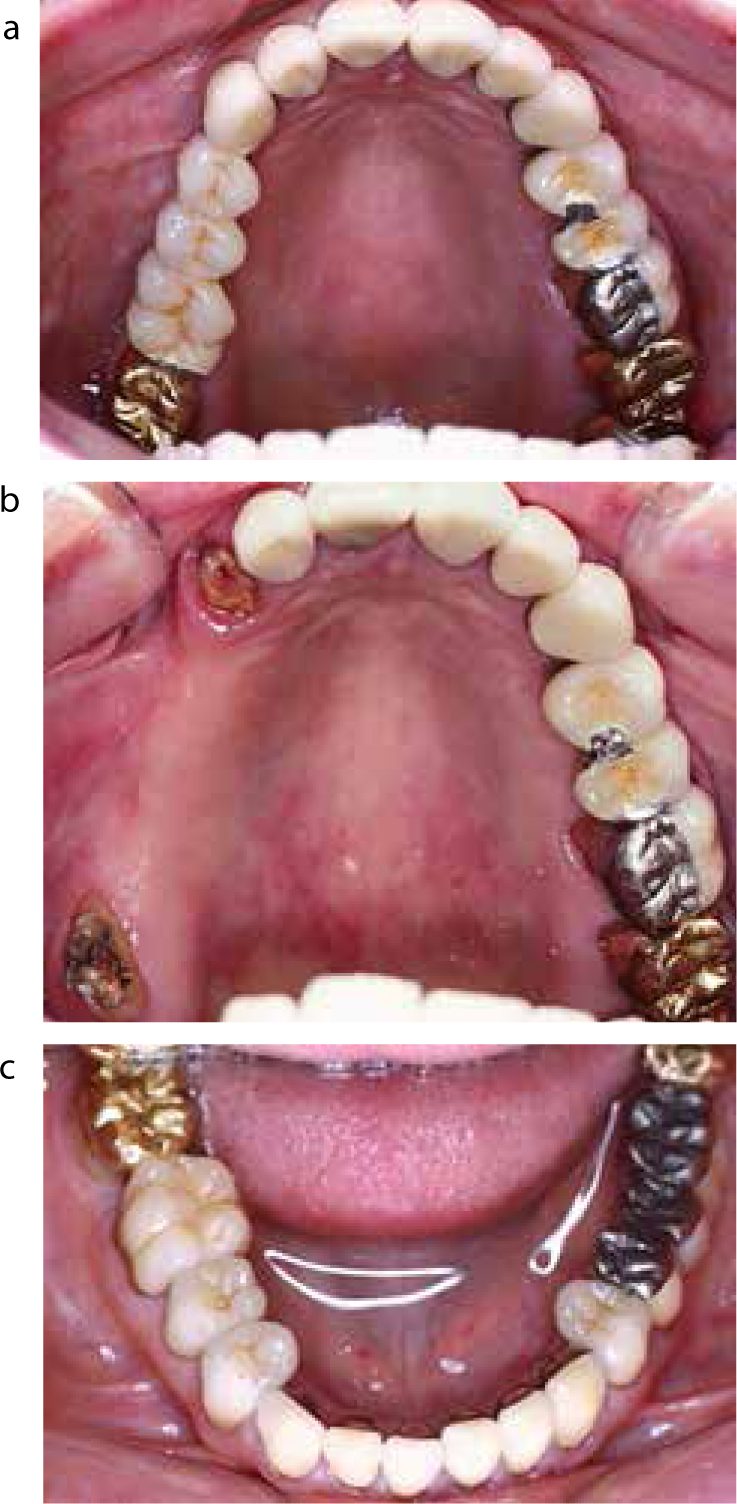

The success and survival rates of the newer adhesive techniques have gradually improved with the evolution of materials. Nohl et al reported an overall success rate of 89% in a retrospective survey of 48 patients treated with 210 metal palatal veneers for anterior palatal TW for periods of up to 5 years.23 They recommended the combination of metal palatal veneers with resin composite luting agent restoring the functional surfaces of maxillary anterior teeth affected by acid erosion (Figure 1).

Direct composite resin restorations have been extensively studied and vary significantly in annual failure rates from 0.7%24 to 26.3%.25 Variations in material properties have been suggested as contributory factors to this wide variation. Microhybrid composite resins have been shown to perform better than the older microfilled resins.

In a series of studies assessing direct and indirect composite resin restorations in predominantly erosive cases, Gow and Hemmings found an annual failure rate of 6.9% in a relatively short follow-up of two years for indirect palatal ceromer veneers.26 The indirect restorations did not offer any advantages over direct composites. Gulamali et al found a similar annual failure rate when assessing indirect and direct hybrid composites in the management of localized TW, with median survival times of 7 years for major failures and 5.8 years when assessing all failures.27 Despite more than 50% of all restorations suffering some form of failure, the authors concluded that composite resin restorations offer a viable medium-term management strategy for TW, in view of the fact that they are non-destructive of tooth tissue when compared with conventional indirect restorations. Despite the huge variation in clinical situations posed and the variety of approaches used to rehabilitate dentitions, which could limit the comparison among different studies, annual failure rates of composite resin restorations appear to be within an acceptable range.

Generalized tooth wear

Traditional treatment methods for patients with severe generalized tooth wear involved full mouth rehabilitation with cast indirect restorations, However, there is a lack of well-designed clinical studies assessing performance and outcomes for this method.6,7 This, combined with high cost and an invasive technique, rendered this approach less favourable when compared to the newer more conservative treatment strategies. Despite rehabilitation of severely worn teeth being common practice, there appear to be deficiencies in the evidence in support of specific techniques or materials.28

The limited data show that rehabilitation of TW with direct composite resin can offer good clinical results, whilst being less invasive than preparations for an indirect approach. Direct hybrid composite restorations have been reported to perform well, even in larger posterior restorations. A number of studies have suggested that material properties may not be as relevant as originally thought when considering longevity of the restorations.29,30 A retrospective case series by Hamburger et al assessed the use of direct composite resin in the management of severe TW caused by erosion, bruxism or a combination of the two.12 A total of 332 restorations were placed in 18 patients over a period of 6 months to 12 years following completion of treatment. Findings were again descriptive, with a total of 23 failures, predominantly in the maxilla, 8 of which were major failures. The authors concluded that the direct hybrid composites offer good clinical performance in cases of severe TW.

In a prospective study assessing 1010 restorations in 164 patients, Milosevic and Burnside suggested that direct hybrid composite resin restorations offer a predictable option in the management of generalized TW, with relatively low failure rates.31 The study highlighted the detrimental impact of attrition and the lack of posterior support on survival outcomes.

Within the current literature, very few studies are available assessing the management of generalized TW, with even fewer comparing the use of direct and indirect restorative techniques.

Vailati assessed the management of severely eroded dentitions with a combination of indirect palatal composite restorations and labial porcelain veneers.32 The study concentrated upon observations on the restored anterior teeth, whilst the posterior teeth were restored but not assessed. The authors used USPHS assessment criteria, with most restorations receiving alpha or bravo scores, however, no statistical analysis of the results were carried out, with findings being purely descriptive. Despite positive findings in the use of ceramic in erosive cases, the risk of chipping under heavy load, coupled with difficulty in repairing ceramic restorations, may prove to be a significant deterrent for its use in wear cases when aetiology might involve some form of parafunction.33

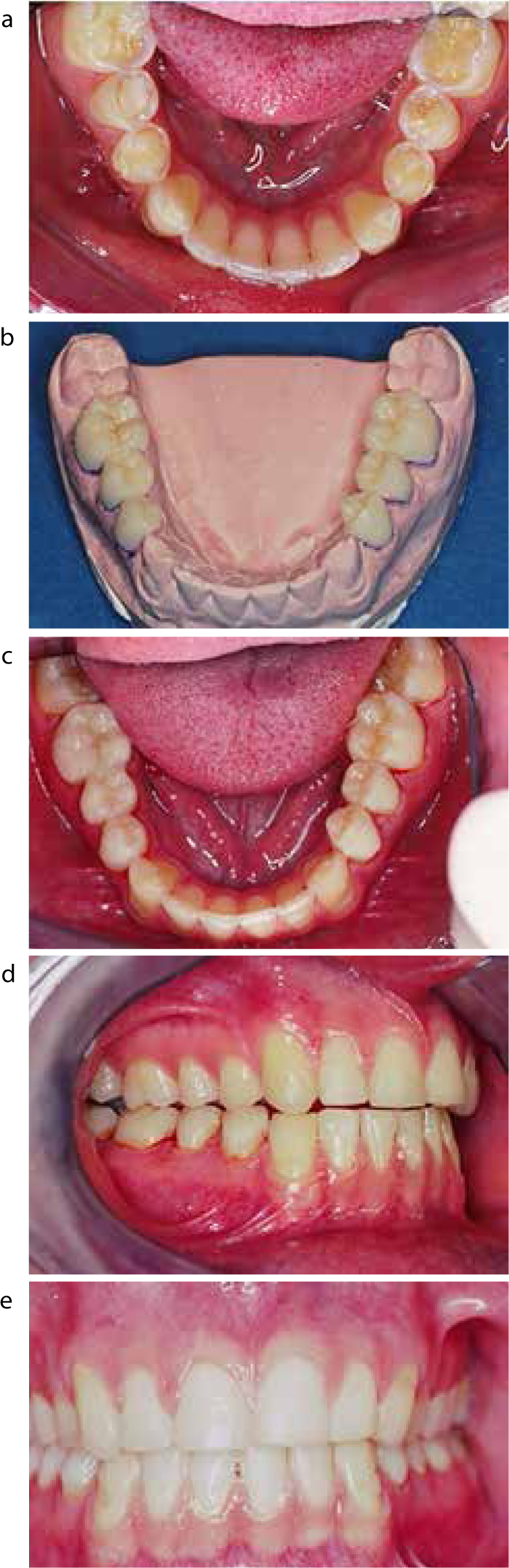

Only one study compared the use of composite resin restorations and traditional metal-ceramic and gold restorations in the severely worn dentitions.34 This study found cumulative survival estimates of 74.5% for indirect restorations and 62% for direct restorations, over 10 years. Over the study period the authors found a strong trend for lower survival of the composite resin restorations in comparison to the indirect restoration. However, these results were not statistically significant. The least failures were noticed with full gold crowns, whilst the metal-ceramic crowns experienced 25.2% failures. Modes of failure with indirect restorations were mostly biological complications. Composite resin restoration, in comparison, suffered more fractures, the management of which was identified as being straightforward (Figure 2).

The aetiology of wear can have a significant impact on the subsequent management. Incorrect diagnosis can prove to have a confounding effect on results. Parafunctional activity can result in devastating forces resulting in the increased risk of mechanical failure at both the restoration and tooth level. Numerous clinical studies on the management of severe TW exclude high risk subjects such as bruxists.28 As such, interpretations of these studies should be carried out with caution. Research into the use of composite resin in such cases have shown mixed results. A few studies have shown good outcomes supporting its use,31,34 however, these were over a relatively short observational period, whilst others have shown poorer outcomes.25,35 It is clear that further high-quality research is required to aid material choice in such cases.

Assessing the occlusal vertical dimension and available restorative space

In the absence of tooth wear the free-way space remains constant due to the continued growth and increase in anterior facial height into middle age.36,37 Localized TW often presents with the occlusal vertical dimension within normal limits.

Generalized tooth wear can often present one of two distinct outcomes:

The list below can be used in combination to determine the correct OVD:

Generally, dentate patients will be able to tolerate even significant changes in the occlusal vertical dimension. The ability of the dentate patient to adapt to changes in the vertical dimension is thought to be down to the the nature of the dento-alveolar structures and associated neuro-musculature proprioception through the supporting periodontal ligament.

The occlusal vertical dimension can theoretically be increased to anywhere along the retruded arc of closure in a dentate patient. Dahl et al41 used a removable appliance to increase the vertical dimension from 1.8 mm to 4.7 mm (mean of 2.84 mm). Hemmings et al25 and Gow and Hemmings26 placed anterior restorations at an increased vertical dimension allowing for separation of posterior teeth of up to 4 mm.

Assessing severely worn teeth for remaining available tooth tissue

Severely worn teeth can still be restored by means of traditional or adhesive techniques. The tooth must be assessed by the following normal parameters in order to determine its restorability. Additionally, the following factors have an impact on restorative material choice:

Space requirements of the proposed restorative materials

The survival and success of restorations is heavily influenced by the physical properties of what material the techniques use and the environment within which it is placed. Conventional cast metal ceramic restorations have the largest footprint, requiring up to 2mm occlusal reduction and can result in up to 72% loss of tooth tissue (by weight).46 All-ceramic crowns can be less destructive, whilst the reduction guides for newer full contour zirconia crowns are comparable to conventional full metal crown preparations. Space requirements for adhesive restorations vary depending on the material properties and function. Adhesive metal onlays require a minimum of 1 mm occlusal clearance, whilst adhesive metal palatal veneers require a minimum thickness of 0.7 mm. Composite resin restorations require a minimum thickness of 1–2 mm, depending on manufacturer guidelines and functional load.

Methods of achieving space for restorative materials

Material choice

Material options available:

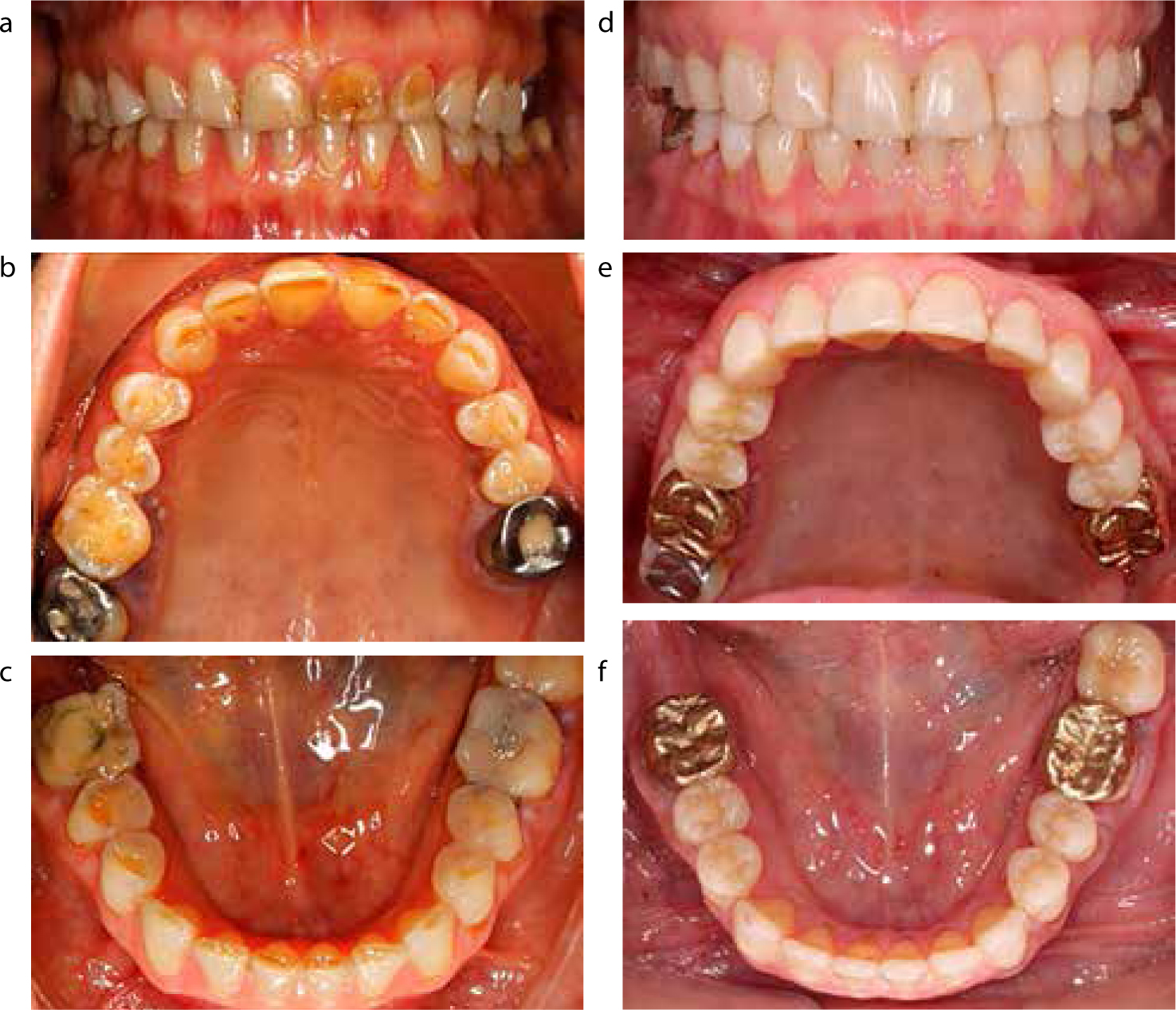

The choice of material to be used for the restoration is critical. Unfortunately, the vast majority of research on the physical properties of restorative materials are laboratory-based trials. Extrapolation of results to the variable clinical environment is fraught with difficulty.50 With such uncertainty concerning the likely prognosis of different treatment options, it is reasonable to delay treatment for as long as possible and provide a conservative approach initially. With careful planning following a ‘tooth by tooth’ assessment, a combination of technologies may provide an extensive but conservative treatment plan (Figure 8).

Managing patient expectations

It is important for patients to have realistic expectations of any future reconstruction. They must be informed of their limitations and potential clinical and financial implications of failure from the outset so that they do not attribute this to inadequate clinical work. The patient will need to be motivated and have a positive outlook if treatment is to provide a successful outcome.