Article

Most practising clinicians have had patients phone the practice saying, ‘My crown has come off’, only to find that, when they attend, it's not just the crown but the entire crown, core and sometimes tooth substance too. Therefore, what for the patient seems like a simple matter of ‘Can you stick it back in?’, turns into, ‘I am afraid it's not quite so simple’. Once patients have viewed an intra-oral photograph or radiograph of the affected tooth, it may be hoped that most will become more aware of this (difficult) clinical situation.

So what are the options?

Conventionally, a new core and, more often than not, a new crown could be considered, given that it is common in situations like this that there are marginal issues which would preclude from recementing the same crown.

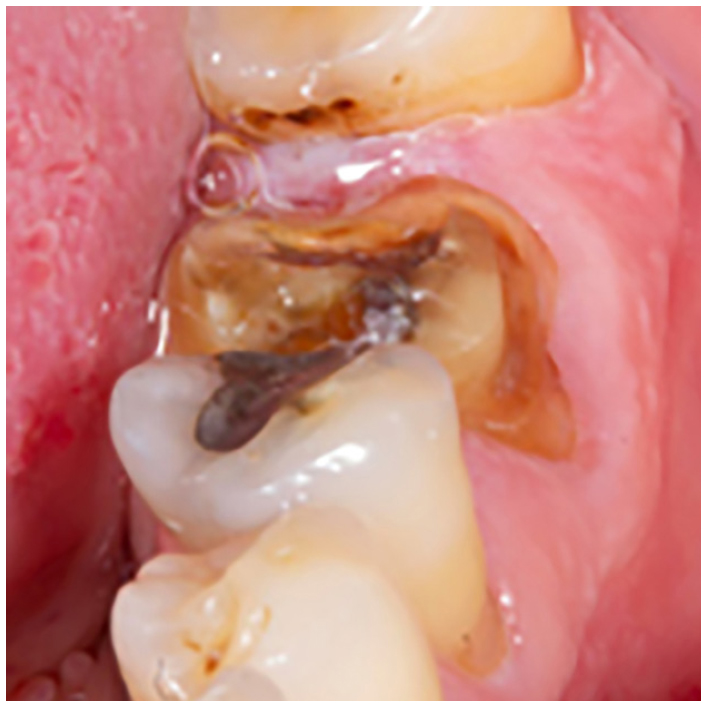

This is such a situation. The patient was a fit and well middle-aged professional man who had lost a crown and core from his LL6. In this case, there was little caries but the original crown was ill-fitting and it was deemed that a new restoration was warranted (Figure 1).

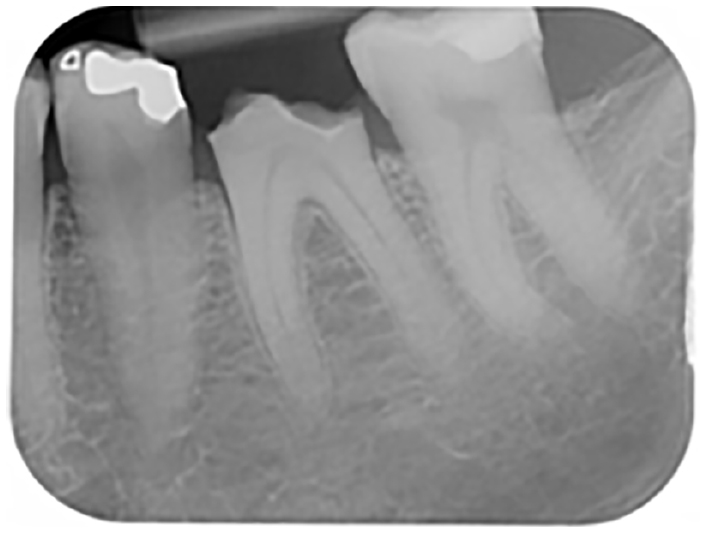

The tooth was unresponsive to cold and the peri-apical (PA) X-ray was unremarkable insofar that there was little to suggest any apical or peri-radicular pathology other than some minor widening of the periodontal ligament space on the mesial root (Figure 2). The lamina dura appeared intact. Indeed, the radiograph did indicate a good dentine bridge which had developed over the distal pulp horn. However, to be realistic, the patient would have to be advised that there was still a likelihood of the tooth requiring endodontic treatment at some point in the future.

Conventionally, it may have been possible to place pins into the remainder of the tooth and build up a core restoration in either amalgam or composite before providing another crown. However, clinicians will be aware that dentine pins not only lead to microcracks in the dentine, but there is also a risk that the pin(s) may be misdirected into the periodontal ligament and/or pulp.1, 2 It is also known, from Saunders and Saunders, that a significant proportion of crowned teeth will become non-vital within a relatively short period of time, even though they may remain asymptomatic.3 So, in this regard, there is a stressed tooth in this instance and, in reality, the last thing that should be contemplated is to stress it further.4 In addition, adhesive dentistry techniques and materials have improved reliability over the past two decades.

So, if it has been decided not to go down the ‘conventional route’, what are the options?:

In the end, and in consultation with the patient and technician, a decision was made to make a milled composite onlay which would be bonded directly to the remaining tooth tissue, with only minimal marginal preparation. A conventional impression was taken, although, had the use of an intra-oral scanner been possible, these are cases where the scanning is made easy as none of the margins, all supragingival, would be difficult to capture.

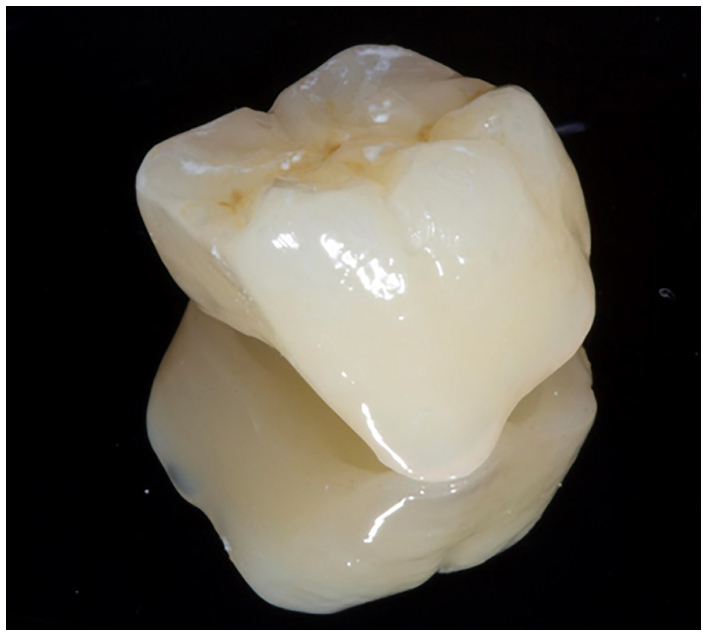

The impressions were taken and delivered to the laboratory. A putty impression had been taken of the failed crown which was temporarily placed back onto the tooth, from which a ProTemp™ onlay was made (Figure 3). With little or no resistance or retention form, polycarboxylate cement was used to cement the temporary restoration, as this has always worked well for the author, who initially had concerns about using a potentially adhesive cement but, over the years, has never found the polycarboxylate cement difficult to clean up using an intra-oral sandblaster. Also, it has never resulted in difficulty of seating the finished restoration.

The laboratory produced the die which was subsequently scanned and then a milled composite onlay was produced. The temporary onlay was removed, the tooth surface, mainly sclerotic dentine, was cleaned using an intra-oral sandblaster and CoJet™ (3M) sand (Figures 4 and 5). The fit surface of the composite onlay was sandblasted, and then the composite onlay was cemented using GC LinkForce™ composite luting agent. Contained within this system is a conditioner for both metal and ceramic, and G-Premio BOND (GC), a dentine adhesive containing the resin 10-MDP. Excess cement was cleaned up and margins were polished (Figures 6–8).

There are many ways to deal with situations like this, but it was considered that an aesthetic and functional restoration could be produced which would adhere well to the remaining tooth tissue and would be easier to cut through in the event that root canal treatment became necessary. Although there are, of course, no randomized controlled trials which back up the treatment plan, the adhesive techniques used are tried and tested, making this a minimally invasive, pragmatic way of restoring a potentially compromised tooth. In all such situations, it is always sensible to explain to the patient that such techniques are pushing the boundaries a little and give them the opportunity of a conventional restoration. In the author's experience, however, the less the handpiece is picked up, the happier the patients remain.