References

An update on discoloured teeth and bleaching part 1: the aetiology and diagnosis of discoloured teeth

From Volume 45, Issue 7, July 2018 | Pages 601-608

Article

In a modern society which celebrates beauty and perfection the demand for an idealized appearance has never been greater. This need for perfection has been driven as much by societal expectations as it has by the media. Age is no longer a barrier to patients' quests for improved appearance, however, greater dissatisfaction regarding dental appearance has been reported in younger age groups.1 The dental industry has considerable responsibility and a versatile armamentarium to drive improvements in appearance, and it is not unusual for patients to approach dentists and allied oral healthcare professionals for advice regarding improving dental appearance as well as facial aesthetics. Visible caries has been reported to lead to more negative judgements regarding social competence, intellectual ability, psychological adjustment and relationship satisfaction.2 Tooth colour has been found to exert an influence on social perceptions2 and, as such, can have an adverse influence on individuals' psychosocial health and quality of life.3 Self-assessed perceptions of tooth discoloration can be very critical. In a self-assessment based national study of 3215 subjects, 50% of respondents reported dissatisfaction with their tooth colour.4 With such high levels of dissatisfaction with tooth colour it is unsurprising that the demand for procedures to improve tooth colour have increased significantly, and there is evidence that this can have a considerable impact on patients' self-esteem.5

Dental aesthetic improvements which a patient may desire can revolve around a number of factors such as; shade, morphology, size, alignment, symmetry and the extent to which the teeth harmonize with a patient's face as a whole. Patients can be very aware of the limitations of their dental appearance, and tooth shade is a commonly cited complaint. In a survey on tooth whitening by the American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry (2012), the single most common factor which respondents reported that they would like to improve about their smile is the ‘whiteness and brightness’ of their teeth.6

Teeth may become discoloured for a number of different reasons, and a thorough history and examination will give clues as to the aetiology of the discoloration, and thus the treatment which is most likely to be effective. It is imperative that the aetiology is ascertained prior to proposing a particular treatment approach.

Aetiology and classification of dental discoloration

Generally speaking, discoloration of teeth may be either intrinsic or extrinsic, and may present in isolation or affect the dentition generally. Tooth discoloration may also be classified as pre-eruptive or post-eruptive in nature. Commonly cited causes of extrinsic and intrinsic discoloration are noted in Table 1.

| Pre-Eruptive Causes of Discoloration | Post-Eruptive Causes of Discoloration | |

|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic |

|

|

| Extrinsic | nil |

|

Extrinsic staining

Extrinsic stains tend to be as a result of molecules bound to the surface of a tooth by either weak chemical or mechanical means (Figure 1). There is no incorporation of the staining molecule into the structure of the tooth. In light of this, techniques which mechanically dislodge or separate the stained molecules from the tooth surface are effective, and these can be minimally interventive. Such techniques include the use of hand and ultrasonic scalers, delivery of an abrasive slurry or powder in jet form and polishing with prophylaxis pastes. This is usually sufficient to remove extrinsic stains. If such measures are not effective, it may be necessary to revisit the diagnosis as the stain may be intrinsic in nature.

In mentioning abrasive and mechanical means of stain removal, it is worthy of note that some toothpastes can be particularly abrasive, and can, when regularly used, increase the surface roughness of teeth. This can, in turn, increase the propensity of the rougher tooth surfaces to pick up stains at a greater rate and magnitude. If such preparations are used for long enough, thinning of the translucent overlaying enamel can result in more of the dentine shining through, exacerbating the poor appearance of the teeth. It is wise to advise patients against the use of such preparations, as the probability of surface enamel abrasion, sensitivity and further deterioration in shade is high. Some smokers' toothpastes and whitening dentifrices are renowned for this.

Intrinsic staining

In contrast to extrinsic staining, most intrinsic stains stem from one of three causes:

A good diagnosis for a good outcome

A systematic approach and accurate diagnosis of the aetiology of discoloration is imperative in achieving a more predictable and effective outcome. Bleaching techniques should not be employed without a thorough history, appropriate examination and special investigations, which may include radiographs and sensibility testing. A thorough history and focused exploration of the nature of the staining will help to identify the cause of the staining and thus the most appropriate treatment. Diagnostic criteria can include:7

Number and distribution of teeth affected

The number and distribution of affected teeth can give an indication of whether the discoloration is due to an individual event, or a more generalized aetiology. Individually stained teeth may result from loss of vitality, previous endodontic treatment, discoloured restorations or a malaligned or in-standing tooth which is more susceptible to staining. If a small number of adjacent teeth are affected, there may be some habit which is predisposing the patient to the staining, such as holding a cigarette adjacent to a particular group of teeth repeatedly. If symmetry is evident in the affected teeth, and they may or may not be adjacent, there may have been some factor such as a childhood infection, pyrexia or a metabolic disturbance which affected the development of a particular group of teeth at a particular time.

Generalized staining can be indicative of either a habit or behaviour which the patient partakes in which affects all of the teeth. This can include the use of mouthwashes with a tendency to stain the teeth, drinking black coffee or tea or similar causes. These stains are likely to be extrinsic in nature. There may also be factors which have affected the whole dentition which are intrinsic in nature. These would include developmental defects such as amelogenesis imperfecta and dentinogenesis imperfecta, or the incorporation of other molecules into the tooth structure at the time of development such as tetracycline staining or fluorosis.

Duration of staining

Stains which have not been present since eruption are likely to be associated with some individual event, action or behaviour. This may be following trauma or treatment, or may be associated with a causative factor such as tobacco use, tea, coffee or a similarly staining agent. Discoloration which has been evident since eruption of the teeth is likely to be as a result of a developmental aetiology, or due to a systemic cause which has resulted in an alteration or incorporation into the crystalline structure of the teeth when they were developing. Tetracycline staining or fluorosis would be an example of this.

Progression in the intensity/darkness of the stain

Discoloration of teeth which is developmental in nature is likely to be stable. Deterioration may occur if, in the case of, for example, amelogenesis imperfecta, the teeth begin to wear and chip, and areas may stain faster due to the rougher and more irregular remaining tooth surfaces. In the case of progressive staining, the history should explore the presence of ongoing aetiological factors such as tobacco use, tea, coffee, and other chromogen heavy activities.

Habits such as smoking, red wine, chromogenic foods and drinks or use of chlorhexidine-containing agents

A thorough history of the discoloration in conjunction with the clinical examination should aid in highlighting any obvious aetiological factors, which should lead to appropriate management, and prevention as necessary.

Colour

An exploration of the colour of the discoloured tooth or teeth can be of considerable diagnostic value. While not definitively diagnostic, in conjunction with a thorough history, this can help to confirm a suspected diagnosis.

Fluorotic teeth may be mottled, speckled, smooth and, in severe cases, can be brown and pitted. In contrast to this, tetracycline-stained teeth can be blue-grey to orange-brown in colour, often with striated horizontal banding present. Dentinogenesis imperfecta can present with a bluish translucent hue, while a traumatized tooth which is non-vital may present with a grey discoloration. A pink tooth may be indicative of internal resorption or of a breakdown in tooth structure, allowing proliferation of periodontal soft tissue into the internal tooth space, which shines through the shell of the tooth.

History of trauma

Single anterior discoloured teeth, particularly if grey or dark in nature, should lead a clinician to enquire if any previous dental trauma has occurred. This discoloration may indicate that the tooth has become non-vital, or has previously been endodontically treated and requires further intervention to improve its appearance. Following trauma, pulp necrosis may lead to blood breakdown products, in particular iron sulphide, which can pass down dentinal tubules and cause a dark grey discoloration. Such colour changes can take many months to develop.

Following luxation injuries, the coronal portion of a tooth may become red in appearance. This can occur due to the venous drainage of the tooth being severed, while the arteriolar supply is maintained. This red colour is indicative of the coronal portion of the tooth being engorged with blood. Over time the discoloration can change to a darker hue as iron sulphide again passes into the dentinal tubules.

As previously mentioned, a pink appearance to an individual tooth may be indicative of internal resorption. In such cases, resorption of the dentine occurs and this is replaced by vascular and hyperplastic soft tissue. As this tissue approaches the surface of the tooth the pink vascular tissue shines through the tooth.

In the case of previously traumatized teeth, a tooth may become yellow and lack lustre. This may be indicative of sclerosis of the root canal, or the impact of a restorative material within the coronal portion of the tooth. The exact aetiology will be confirmed by a thorough examination and appropriate radiographs.

Previous treatment of affected teeth

An exploration of any previous treatment of the affected tooth or teeth is necessary. It is likely that teeth in isolation will present in this manner, and discoloration may be as a result of an increased surface roughness, or due to deterioration of a restorative material over time. If a particular material has been used in a number of teeth, and the age of the material is comparable, more affected teeth will be evident, although the discoloured restoration should be well demarcated and the stain may not affect the tooth structure itself, indicating polishing or refreshing of the restorative material.

Commonly, previous endodontic treatment or teeth which have lost vitality can present with a grey discoloration, and appropriate investigation and management should be instigated. In certain circumstances, endodontic obturation materials which have been used overseas may result in alternative discolorations. An example of this is the endodontic obturation material ‘Resorcinol-formaldehyde resin’, more commonly known as ‘Russian Red’, and is recognizable from the change towards a red hue of the tooth. Mineral trixoxide aggregate is also known to result in a greying of tooth structure when used as an obturation material (Figure 2).

Familial considerations

An exploration of any family members being affected by similar discoloration to the patient is useful as part of the history when generalized discoloration of the dentition is evident. This is particularly pertinent in cases of amelogenesis and dentinogenesis imperfecta, as both can run in families. Amelogenesis imperfecta can have different inheritance patterns depending on which gene is affected and, as a result, it is difficult to predict if a person will be affected or not. The most common mutation affects the ENAM8 gene, and these mutations are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, meaning that only one copy of the affected gene is sufficient to cause manifestation of the disease. This disorder can also be caused by mutations of the MMP20,9 KLK4,10 FAM83H,11 C4orf2612 or SLC24A413,14 genes.

It is worthy of note that children who present with fluorosis may also have siblings with similar discoloration and, far from being hereditary in nature, mindfulness and adjustment in fluoride exposure can help in preventing this in younger siblings.

Associated syndromes and diseases

A number of diseases and syndromes have been reported which can affect the colour of teeth. These tend to have a metabolic underpinning which results in changes in the appearance due to developmental alterations. Examples of these are listed in Table 2.

| Disorder | Discoloration | Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Alkaptonuria | Brown discoloration | Inborn error of metabolism which leads to a build-up of homogentisic acid, ultimately affecting the permanent dentition. |

| Congenital erythropoietic porphyria (Gunther disease) | Red or brown discoloured teeth | Congenital disorder, with likely metabolic impact of disorder at time of development. |

| Hyperbilirubinemia during the years of tooth formation | Yellow-green or blue-green discoloration | Incorporation of bilirubin into the dental hard tissues |

| Thalassaemia | Blue, green or brown tooth discoloration | Metabolic impact of disorder at time of development |

| Sickle Cell Anaemia | Blue, green or brown tooth discoloration | Metabolic impact of disorder at time of development |

| Cystic fibrosis | A variety of discoloration | May be due to common prescription of tetracycline during tooth development, or due to defective cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator, which is known to be involved in enamel formation |

Summary

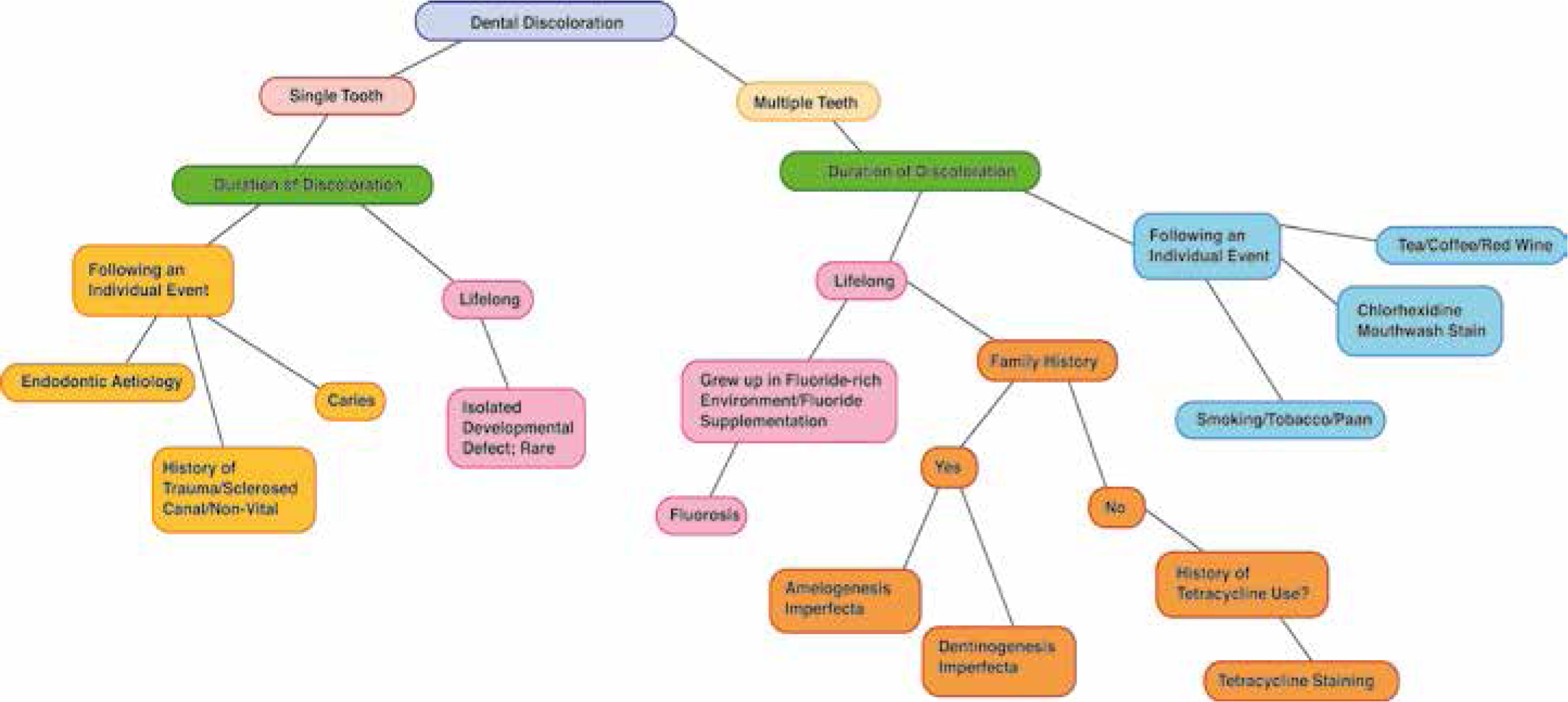

This article has aimed to deliver an overview of the classification and causes of dental discoloration. Figure 3 presents a mindmap showing a diagnostic tree which can aid in diagnosing causes of discoloration. There are a wide range of aetiological factors and clinical manifestations which are encompassed by the term discoloured teeth. Accurate diagnosis is pivotal in giving the clinician and thus patient an indication of the appropriate treatment modality and likely outcome.

A second part will review the mechanism of action and various clinical approaches using bleaching agents to manage discoloured teeth.