Article

Current thinking on cavity design revolves around an increased understanding of the need for extremely conservative cavity preparations that are determined mainly by the extent of the caries at the enameldentine junction, rather than upon preconceived ideas embraced by the term ‘outline form’.1

However, considerations of the whole basis of restorative dentistry as a method of managing caries and its sequelae are even more important. It is all too easy to assume that restorations are the perfect and ultimate way of managing caries, but restorative dentistry has many shortcomings and it is necessary to bring these into focus before making any predictions as to prospects for the future. This article looks briefly at some of these shortcomings and forecasts the way in which many of them will have been overcome by the year 2000.

Shortcomings of restorative dentistry

Restorations do not cure caries

Restorative dentistry is based upon the concept that the surgical excision of carious tissue followed by the restoration of the tooth is the treatment of choice for caries. These procedures in themselves, of course, do not cure the disease; rather, the cause remains and lesions may therefore progress elsewhere in the mouth or, subsequently, occur as secondary caries near the original sites. A true cure for this disease only occurs when the iconic balance between the loss and uptake of calcium and phosphate ions from the lesion can be made to swing in the overall direction of remineralization. The implementation of appropriate preventive measures, such as dietary control, frequent fluoride applications and plaque control, are the main established ways of engendering this.

Caries is difficult to diagnose

Although dentists are the experts at diagnosing caries, it should not be taken for granted that they are infallible. Dental epidemiologists have battled with the issue for years and they have found it necessary to institute comprehensive training programmes for their examiners. In the treatment setting, the size of the problem was demonstrated by Rytomaa, Jarvinen and Jarvinen,2 who reported wide variation in the diagnoses made by 12 dental school teachers who examined the same group of 10 patients. The problem exists in relation to the secondary caries as well as to primary caries, as demonstrated in a simulated clinical study where more than a five-fold variation was found among nine dentists as to which teeth were thought to have caries among a set of 228 extracted restored teeth.3 The dentists cannot all have been correct in their diagnoses, therefore some must have been wrong. There was also considerable lack of correspondence between the teeth the dentists had considered had caries and those found, after sectioning, to have caries.

Treatment decisions are inconsistent

Differences in treatment decisions made by staff and students, or between the two members of staff, are well known to those who work in dental schools. Yet, it is all too easy to feel confident in planning routine restorative treatment and for practitioners to consider their prescribing patterns to be entirely justified. However, surprisingly little is known of the natural history of caries and the extent of variation in this natural history for different individuals and different communities. It is therefore not suprising that the criteria indicating the appropriateness of operative intervention in its management are open to considerable debate; certainly, there is no universal agreement within the profession as to what these criteria should be, though attempts at defining them have been made.4

This lack of accepted criteria at a time of markedly reducing caries in prevalence in the developed countries, partly explains why, in a longitudinal study of treatment based upon the UK 1978 Adult Dental Health Survey, the fillings placed by practitioners in the GDS bore little relationship to those predicted on the basis of the survey findings.5 Indeed, it was found that almost twice as many tooth surfaces had been filled in the first year following the survey than had been predicted on the basis of survey examinations, but that only one quarter of the tooth surfaces classified in the survey as carious or with failed restorations were among these. It follows that seven eighths of the surfaces that received fillings had not been identified in the survey as being in need of restoring.

To examine the matter further, a study was set up to examine the extent of variation among treatment plans formulated under as near to normal working conditions as possible.6 When 15 dentists each examined and planned treatment for a group of 18 young adults, the number of positive treatment decisions made by the different dentists ranged from 20 to 153. The inescapable conclusion is that many restorative decisions must be incorrect.

Dental attendance and restorations

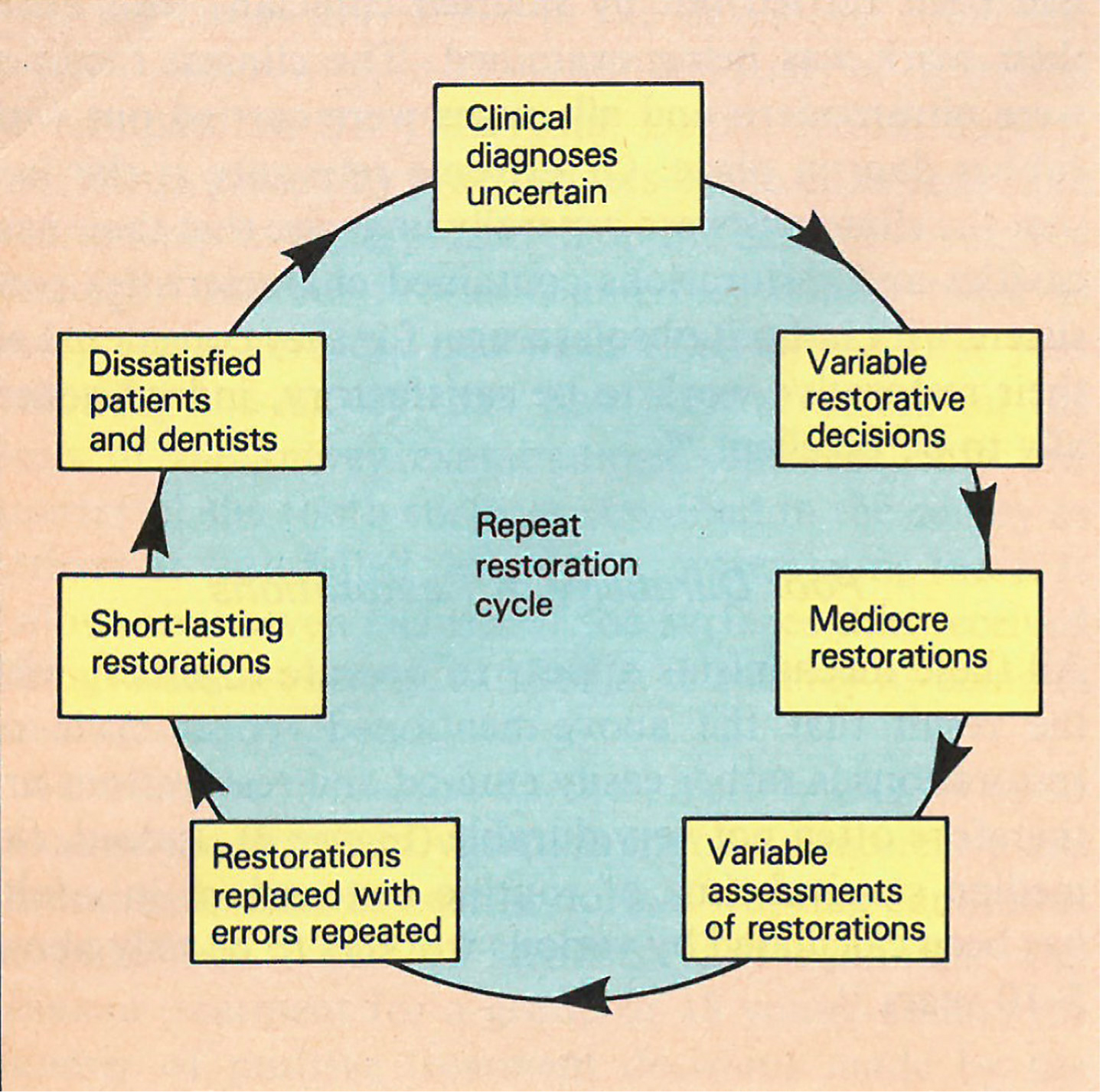

In a 5-year study of dental treatment provided for a random sample of dentate adults, it was revealed that the number of tooth surfaces restored over the period went up markedly as the number of courses of treatment rose.7 It was also noted that the more restorations a person had at the start of the study, the more he/she was likely to receive in the future, for a repeat restorative cycle becomes established. Further, it was found that 50% of the restorative treatment was directed at just 12% of the patients. These people were at a high risk group who were at particular risk of having their restorations replaced for, somewhat inevitably, the ratio of replacement restorations to first-time restorations in an individual was found to increase markedly as the overall amount of restorative treatment rose. Indeed, the ratio was over five times greater for patients who received a lot of restorative treatment compared with those who received little restorative treatment.

In a dental service based upon the restorative philosophy, it seems undisputed that frequent attendance with a dentist is linked with having more restorations. This observation should, of course, be balanced against the known fact that dental caries and restorations, through very prevalent, are themselves unevenly distributed. Further, it should be appreciated that those who attend a dentist relatively frequently do tend to achieve better dental health; they generally have several more teeth than infrequent attenders.8

Changing dentists

This 5-year study also revealed that, among frequently attending patients, those who changed their dentists at least once, received an average of 13.6 restorations over the period compared with 7.4 for those who stayed with the same dentist.9 It is clear that the restorative cycle is fuelled by a change of dentist.

Poor quality restorations

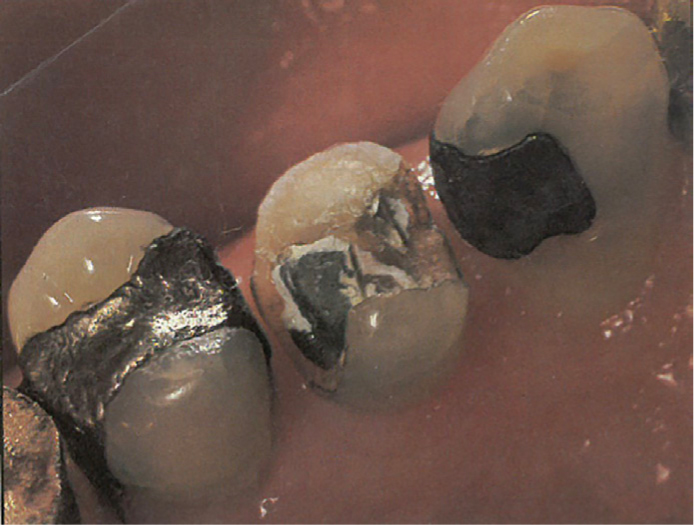

An objective study has demonstrated that clinicians often do not know what has caused restorations to fail.10 Indeed, when the clinicians in this study were asked to reappraise the same restorations several weeks later, they gave different reasons in 47% of instances. It is therefore inevitable that, when restorations are replaced, the errors are often not put right; indeed, frequently they are repeated, thereby adding further to the restorative cycle.10 With occlusal amalgam restorations in particular, the cavosurface angles are often too high, with the inevitable consequence that the all-critical amalgam margin angles are too low.1 Where this occurs, the new amalgam margin is often carved short of the cavity margin. This means that the marginal defect that forms as the amalgam margin breaks down, rapidly assumes large proportions at these sites (Figure 1). In other regions there is excess amalgam in the form of flash which is liable to break off, also causing a ditched appearance to the margin of the restoration (Figure 1).

These objective observations were made in spite of the fact that all the restorative procedures monitored had been carried out by salaried clinicians who knew their work was being examined. The clinical facilities were ultramodern and all stages were carried out with rubber dam in place. Of extreme relevance is the fact that clinicians were generally unaware that their new cavities and restorations contained characteristics consistent with in-built obsolescence, for they considered all their restorative work to be satisfactory, indeed generally to be excellent.10

Poor durability of restorations

All these mechanisms appear to operate together, with the result that the above-mentioned repeat cycle of restorations is rather easily entered and restorations are therefore often not very durable (Figure 2). Indeed, the median survival time of routine restorations in adults has been calculated by various workers to be only about 5–10 years.11

Consequences of poor durability

Restorations that are judged to have failed are usually replaced, in which case the cavities are invariably made substantially larger and the teeth weaker. It is clear that the restorative treatment becomes more complex as the replacement cycle progresses (Figures 3 and 4).

The response of patients

In spite of all these shortcomings of restorative dentistry, frequently attending patients often appear to accept repeat restorative treatment. This may be because of a lack of knowledge of any alternative, or perhaps through a lack of courage to challenge it. Certainly, it has been shown that the present restoratively orientated dental service is offering something that many people do not want and that it does not offer an acceptable way of meeting their needs.12

Prospects for the future

Patients will demand a preventive philosophy

The media is playing an increasing part in providing the public with information about the possibilites for prevention. It is therefore clear that the consumer will increasingly demand a dental service that makes sense to him and prevention makes good sense, especially in the context of increasing dental charges. The regular attender will become less ready to accept an apparently unending commitment to having his/her teeth restored repeatedly once he/she is aware of the preventitive option that modern dentistry can offer. In addition, many people who currently avoid dental treatment, as much as possible, will come to accept a care service with a predominantly preventive image.

Dentists will practise a preventive philosopy

By the year 2000, just as many consumers of the dental service will have made up their minds to demand a preventive approach to the management of caries and existing restorations, so also will large fractions of the dental profession who have come to realize fully the inappropriateness of restorative dentistry carried out with all the shortcomings described above. They will appreciate that a preventive philosophy of practice makes more sense, both to their patients and to themselves, and will have found that, into the bargain, their quality of life and incomes will have improved.

To bring out this change, there will have been a major switch by dentists towards adopting a preventive approach to managing early carious lesions and mechanically imperfect restorations. This will blunt the adverse effects of variable clinical diagnoses and treatment decisions, making them less critical than in the earlier restorative era, and relieve the enormous burden with which many dentists currently feel saddled. Practitioners will be limiting clinical intervention to the absolute minimum and giving prevention the opportunity to work. Where there is, at present, adherence to the maxim ‘if in doubt, fill or refill’ dentists will take a pride in adopting the philosophy of ‘if in doubt, prevent, wait and reassess’. The danger of receiving more restorations as a result of regular visits to a dentist will be a thing of the past and patients will tend to stay with the same dentist.

Restorations in the year 2000

There will still be a need for restorations in the year 2000, but the number will gradually reduce to reach a level of about one quarter of that at present. It may be some years into the 21st century before this level is obtained, for it will be a while before the profession becomes fully confident in the criteria that indicate the need for operative intervention.

Highly quality restorations

When restorations are required, they will generally be of a higher quality than at present. Cavity designs will be much more refined and conservative and, for amalgam, they will be based upon those described in the previous article in this series.1 Thus, the extent of cavity preparations will be determined largely by the extent of the carious lesions and the term ‘outline form’ will have been eradicated from the dentist's vocabulary.

The achievement of high quality restorations with the least amount of in-built obsolescence will be a matter of pride and professionalism and patients will be aware of this quality. Rubber dam will be used much of the time for, by the year 2000, in the USA it will already have been deemed malpractice to undertake a restorative procedure without rubber dam in place The protection societies in the UK will become increasingly uneasy about defending a dentist when a restoration, placed without rubber dam, fails within a period of, say, five years.

Restorative materials

With the emphasis on high quality restorations, albeit fewer of them, the search for the best routine material will continue. Amalgam and composite will both be commonplace, though only a restricted list of well tested materials will be approved for clinical use. All the approved amalgam alloys will be of the high copper nongamma-2 type and only single-paste composite materials filled to at least 75% by volume will be acceptable. Much research will have been directed towards the development of biologically active restorative materials, including, intermediate enamel and dentine bonding materials which will have advanced immeasurably from those of today. Nevertheless, considerable doubt will have been expressed about the long-term, cavity-sealing properties of these materials. This, together with adverse publicity about the possible health hazards of new mercury, will have boosted the development of a new generation of glass-ionomer-based restorative materials which will be showing great promise at becoming the number one, general-purpose material for repairing teeth. Castable glass will have superseded porcelain.

Sealing over caries

Filled sealants will have been in widespread use for several years for the therapeutic treatment of questionable or early carious fissures, without the need for cavity preparation.13 In addition, laser technology will have been developed sufficiently to enable synthetic apatite to be used as a ‘solder’ that will fuse to the enamel surface across sound or slightly carious pits and fissures,14 rendering them permanently impervious to further caries. However, it is likely that practitioners would only be allowed to carry out this treatment subject to a special license issued after appropriate training in the method.

Filling over caries

The need to remove all the caries at the enamel-dentine junction when undertaking standard restorative procedures with materials that bond well to the dental tissues will have been subject to serious challenge. Indeed, the author predicts that the year 2000 will see the publication of a large, well-designed, 8-year study in which carious tissue is removed with excavators only and the residual lesions are impregnated with a polyantibiotics gel, which also serves as a bonding agent for the restorations. These so-called ‘impregnation restorations’ (Figure 5) will be shown to perform better than the control restorations for which all the caries is removed from the enamel-dentine junction.

Sealing deteriorating restorations

The impregnating agent will also be showing promise in a rather different role, one in which it is used as a sealant at the edges of deteriorating restorations wherever caries is not evident in the outer surface of the enamel. Under certain circumstances it will serve to arrest any secondary caries that may be present deeper down. Against the background of a more selective approach to replacing defective restorations and in response to a greater understanding of disadvantages of so doing, the impregnating agent will have the great additional psychological benefit to dentists of providing a sense of respectability about leaving imperfect restorations in situ.

A preventive dental service

The overall effect of all these mechanisms, together with changed philosophy of dental practice towards a truly preventive service, will be that the median life of ‘routine’ restorations provided by the GDS will be found to have doubled from the present time. Public knowledge of this, together with a general appreciation of the various minimally invasive of non-invasive techniques for managing caries and its sequelae, will be very influential in making dentistry more acceptable to those whose present habit is to keep away from dentists as much as possible. Having got their ‘product’ right, preventively-orientated dental practices will boom. A change in the objectives of the GDS from having a proclaimed aim of achieving ‘dental fitness’ to one of ‘preventing dental disease and achieving dental fitness’ will have had a profound effect in producing this metamorphosis.