References

The application of occlusion in clinical practice part 3: practical application of the essential concepts in clinical occlusion

From Volume 46, Issue 2, February 2019 | Pages 100-112

Article

Having carried out a clinical assessment of a patient's occlusal scheme and, where indicated, attained the appropriate occlusal records to permit further evaluations to take place (as discussed in Parts 1 and 2), the next stage would logically involve the application of any information gathered to attain a desirable functional (as well as aesthetic) outcome with the proposed treatment plan.

A firm understating of the basic concepts in clinical occlusion (largely based on the guidelines for good occlusal practice)1 inclusive of the concept of the ‘ideal occlusal scheme’,2, 3 as well as acquiring the skills to attain the relevant occlusal records and use of associated apparatus, is important to achieve an optimal outcome during the occlusal rehabilitation of the patient.

Part 3 of this series will aim to appraise the circumstances when it may be appropriate to conform to the patient's existing occlusal scheme as well to consider when a re-organizational approach towards occlusal rehabilitation may be more suitable.

This article will also explore the aspect of patient ‘adaptability’ to occlusal changes. The cumulative gathering of knowledge surrounding this aspect is indeed challenging some of the traditionally maintained concepts in clinical occlusion.

How and when to take the conformative approach to restorative rehabilitation

The conformative approach to the restorative rehabilitation of a dentition would involve the provision of restorations to any of the affected teeth at the ‘pre-existing occlusal scheme, without incurring a change in the occlusal vertical dimension (OVD) and in the existing intercuspal position (ICP)’.4 Within the framework of the primary care setting, it is likely that the majority of the routine restorative treatment being provided will involve taking the conformative approach.5 There are, however, some circumstances where the conformative approach would generally not be indicated. Such circumstances may involve and/or include:3, 6

Most experienced practitioners will be all too aware of the consequences of failing to conform to the pre-existing occlusal scheme effectively, which may cumulate in possible deleterious longer-term consequences,5 that are often noticed in hindsight.

The conformative approach with direct (chairside) restorative materials

From a practical perspective, when a conformative approach is to be taken, it is imperative to leave sufficient reference points to make sure that the new restorations do indeed conform to the existing occlusal scheme.3

Accordingly, when planning the making of a direct restoration for a tooth that is not involved with the provision of guidance to the mandible during any dynamic movements, it is appropriate to mark up the pre-operative centric stops in the intercuspal position (ICP) using articulating paper (as described in Part 2). The application of a thin layer of copal varnish prior to the actual process of marking the occlusal contacts with articulating paper will not only help to transfer marks from the paper, but also help to retain their presence for the duration of the procedure.7 Photographic records, video records to observe the dynamic relationship, as well as written records may also prove helpful. Pre-operative stops may be marked up in one colour; upon completion of the restoration, a different colour of articulating paper may be used − the presence of co-incidence between the two sets of markings together with evidence of patent Shimstock foil holding contacts in the intercuspal position (that may be heavier in the case of the posterior dentition), would be supportive of having effectively conformed to the pre-operative occlusal scheme.

In the event of the centric stops being positioned on the restorative material, it is imperative to ensure that an adequate thickness of material is present at the aforementioned location so as to avoid premature failure. Furthermore, the occlusal contacts formed on the restoration should be of the pin-point variety as opposed to the broad-rubbing form, which may otherwise inadvertently serve to provide occlusal contact during excursive movements of the mandible. As part of the final verification of the completed restoration, the absence of any occlusal interference should also be ascertained.

Where the affected tooth is involved with the provision of mandibular guidance and the use of a plastic restorative material has been selected to restore the occluding aspect of the tooth that provides this function, the situation is somewhat more complicated. With the use of plastic based materials, it may be acceptable to retain this feature amongst anterior teeth, as the level of occlusal loading is likely to be significantly lower than with the case further posteriorly in the oral cavity (assuming that an appropriate dimension of restorative material can be placed in the areas of functional loading).8 Indeed, there is good evidence to support the role of direct resin composite restoration for the functional-aesthetic rehabilitation of anterior teeth that have been significantly affected by the condition of tooth wear (TW), where guiding contacts will likely be provided by the restorative material (inclusive of cases treated by placing the restorative material in a supra-occlusal location); however, minor failures are to be expected.9, 10, 11

Further caution should be applied in the case of a posterior tooth, as the occlusal loading will be higher, with the heightened risk of fracture or premature wear. Most experienced practitioners will of course be aware of the relatively lower tensile strength offered by silver amalgam, as well as the risk of bulk fracture as a common cause of failure of direct posterior resin composite restorations, especially associated amongst patients who may display a tendency towards parafunctional jaw clenching and grinding habits and where micro-filled type materials may have been prescribed to fabricate the restorations.12, 13, 14 A choice therefore needs to be made in relation to the retention of this feature in the post-treatment scenario.

If the decision has been taken to retain the role of the occluding surface with guidance, pre-operative centric stops together with the dynamic occlusal contacts should be identified and marked up using articulating paper, as described in Part 2 of this series. A pre-operative silicone index/key can be prepared of the occluding surface of the tooth either prior to carrying out any tooth preparation, or following a mock-up protocol (as described below in relation to the canine rise restoration − where the patient's jaw crudely serves as a form of articulator in trialling differing occlusal prescriptions) or from a diagnostic wax-up. The information provided by the silicone key can be used to help guide the application of resin composite in a manner that will aid the transfer of the occlusal prescription and thus copy the occlusal anatomy into the definitive restoration. Final adjustments may be made intra-orally to ensure that the correct functional form is ultimately attained. Patients should, however, be advised of the heightened risks of mechanical failure, as considerable stresses will be incurred by the dental material in this location. The use of a silicone key fabricated prior to the removal of a large discoloured, with perhaps some marginal leakage yet functionally sound, anterior composite restoration may be useful to copy the functional prescription in the replacement restoration and therefore conforming to the existing occlusal scheme.

In some cases, the decision may be taken to lower the mechanical burden on the material by eliminating the role of the occluding surface in providing mandibular guidance (maintaining the centric stop only). This must, however, be undertaken with caution as it may result in the tooth being visibly shorter in height than from its pre-operative status. The latter may not only have possible aesthetic implications, but also include the prospect of transferring the guiding contact onto another surface in the patient's oral cavity, which may prove less favourable. The actual effect of adjusting away the guiding contact can be determined using a set of diagnostic casts mounted in centric relation (as discussed in Part 2), whereby selective grinding can be performed on a set of dental casts.

Should the above circumstances prove unacceptable, a decision may be taken to prescribe an indirect dental material/restoration that offers superior mechanical properties (ensuring that valid informed consent is attained), or to consider the addition of dental material (circumstances permitting) at another location in the patient's mouth, so as effectively to ‘lift’ the affected tooth out of providing mandibular guidance. In doing so, this would aim to shift this burden of responsibility to another tooth (Figures 1 and 2).

Indeed, the approach of providing a ‘canine rise/Stuart lift restoration’15, 16 is one frequently prescribed by the authors and can prove very helpful in dealing with patients who present with recurrently failing class IV restorations at their central maxillary incisor teeth, where the loss of canine guidance as a result of tooth wear may have culminated in the former teeth becoming involved as a working side or non-working side interference, and has been described in further detail below, as well as for the overall management of patients presenting with TW.15

The canine rise restoration

This form of restoration acts by altering the cuspal incline of the canine teeth so as to provide a canine-guided occlusion, whilst retaining the occlusal vertical dimension constant. ‘The prescription of a riser restoration is however, not advocated for use on teeth that do not display signs of wear’.

As part of the process of providing a canine-rise restoration, a complete occlusal assessment, as described in Part 1 of this series, should be carried out. The placement of the riser restoration will result in an alteration to the aesthetic zone. Thus, in order to help gain informed consent, a mock-up of the riser restoration should be undertaken, achieved by simply drying the canine tooth and placing resin composite (without any bonding) on the canine, thereby allowing the patient to visualize the aesthetic outcome.

The technique described here relates to the placement of resin composite in a direct manner to restore a worn maxillary canine. Resin composite has the merits of being aesthetic, as well as allowing for contingency planning, should the patient be unable to tolerate the restoration. Adjustments can also be made readily, or the restoration removed with no significant harm being incurred. Resin composite is also a relatively inexpensive material. If the patient can tolerate the restoration, a more robust restorative material in the longer term can be considered.4, 15

The appropriate shade of resin composite is then chosen. The centric stop on the canine tooth should be identified and marked using articulating paper. Following isolation, the enamel tissues should be cleaned using air abrasion or a slurry of oil-free pumice and the tooth prepared to receive a resin-bonded restoration. For a severely worn canine tooth, a dentine shade of resin composite may be required along with the enamel shade, taking great care only to add material superior (incisal) to the marked centric stop. The inadvertent placement of composite resin on or inferior (gingival) to the centric stop will culminate in an increase in the patient's occlusal vertical dimension.

The efficacy of the completed restoration placed should be carefully evaluated; ideally it should provide canine guidance, which can be verified by asking the patient to demonstrate a lateral excursive movement. The centric stop should be coincident to the one pre-operatively, with no change in the OVD. The guidance should result in disclusion on both the working and non-working side. Articulating paper can be used to aid the verification process. The ramp provided should harmonize with the residual occlusion, otherwise displacement and/or mobility of the canine teeth may result.

The conformative approach with indirect restorative techniques

This occurs when providing indirect restorations affecting the occlusal surfaces that will be designed to conform to the existing occlusal scheme. Also, in the case of a single unit posterior crown/onlay, where the affected tooth is neither involved in providing any form of mandibular guidance during any lateral excursive or protrusive movements and does not carry the first point of contact in centric relation (CR) − the retruded contact position (RCP). Also, following the process of completing the tooth preparation, the use of hand-held casts to fabricate the restoration would be deemed sufficient; in this case, an intercuspal (ICP) record may be taken (if required), as discussed in Part 2.5 Upon the process of try- in and fitting of the definitive restoration, it is important to verify that the centric stops pre-and post-cementation are co-incident, with the presence of patent holding contacts elucidated, using a section of appropriately supported Shimstock foil (analogous to the processes as described above for a direct restoration).

In the case of providing a limited number of multiple posterior restorations (three units or less − inclusive of dental bridgework) where the teeth will not be involved in providing mandibular guidance (such as for a patient displaying a canine-guided occlusal scheme), it would be sensible to attain a facebow record as well as an ICP record so as to enable the use of either an average value articulator5 or a semi-adjustable articulator, where average values may be applied to programme the device, as described in Part 2. This will hopefully provide the dental technician with further information on how best to develop the anatomical form of the restorations in relation to features such as the; cusp height, cusp angles and the placement of the cusp tips and grooves, as described in Part 1.

When preparing multiple teeth (three or less), in order to maintain reference points it may be sensible to prepare a single tooth and obtain an ICP record immediately following the preparation, by interposing a dimensionally stable registration medium (as an appropriate form of PVS bite registration material or a cold-cured acrylic) between the opposing occluding surfaces in the intercuspal position. As the subsequent teeth are prepared, the first record is positioned and the recording process is repeated. Following the final preparation, the individual records are positioned and can be incorporated in an overall ICP registration. Confirmatory Shimstock holds can also be recorded from the other teeth. These records can then be used to mount the working cast against the opposing pre-mounted study cast. In the case of a single unit anterior crown that will not be involved in providing mandibular guidance during any dynamic movements, and/or in the case of the guidance being readily established from the adjacent teeth, the protocol as for a single unit crown as described above would be applicable.

However, were it established that the given anterior tooth does indeed have a critical role in providing guidance, and there is the desire to preserve/‘copy’ this function into the definitive indirect restoration then, accordingly, a set of accurate pre-operative study casts should be fabricated, a facebow record taken and, if necessary, a record of the intercuspal position also attained.

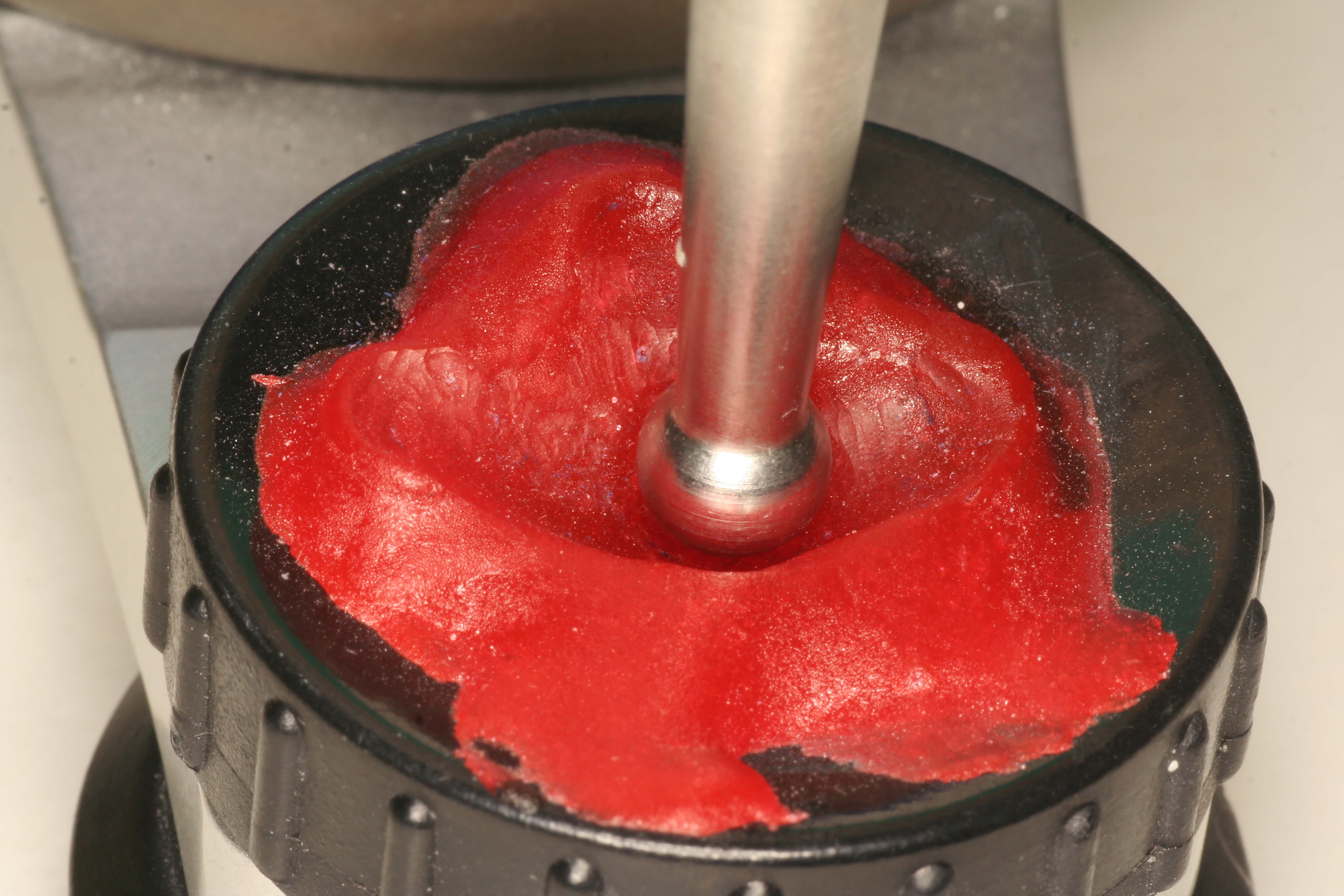

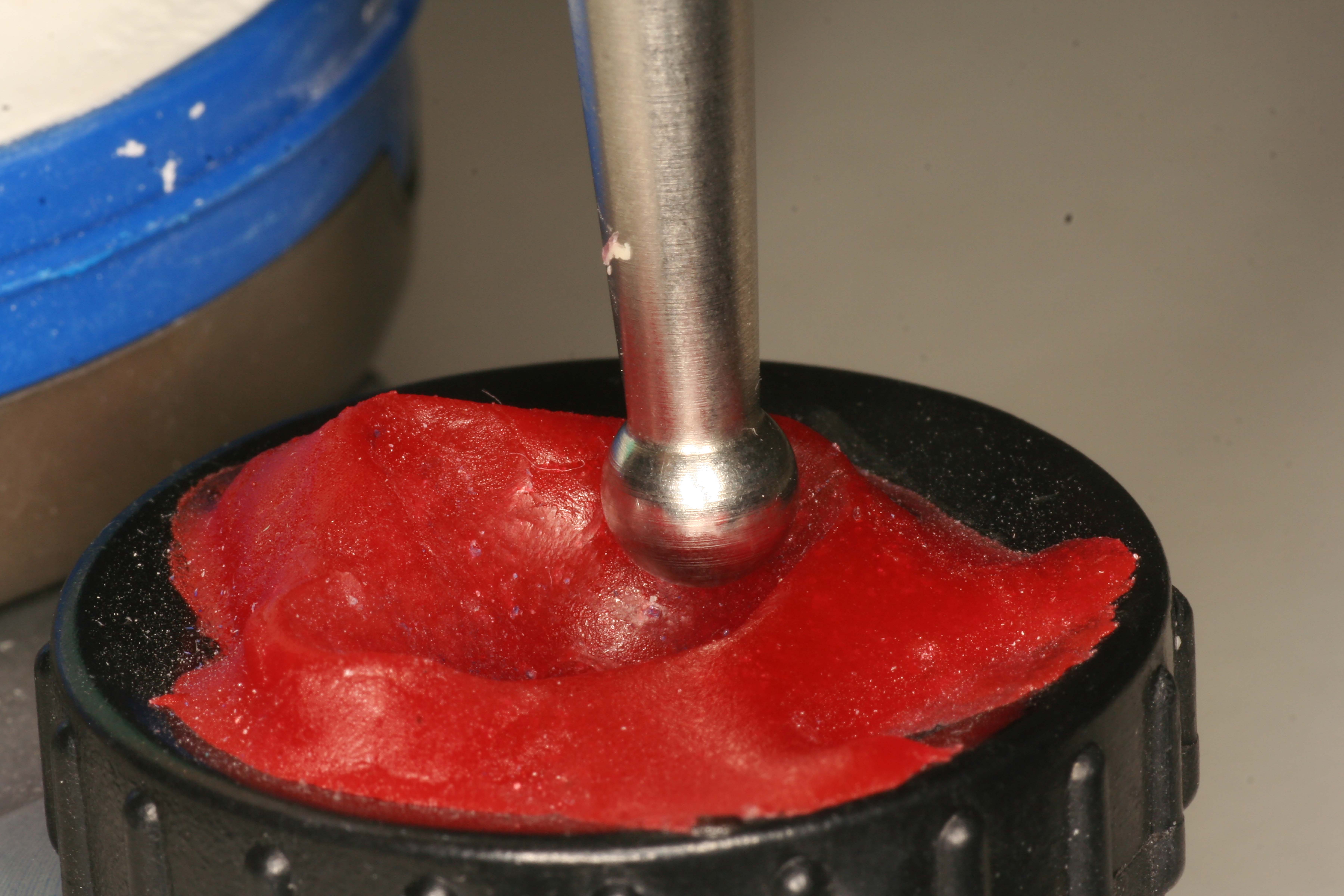

Using the above records, the diagnostic/pre-definitive restoration casts can be suitably mounted on a semi-adjustable articulator in the intercuspal position. A customized incisal guidance table (also sometimes referred to as an anterior guidance table, or incisal bite table) should then be fabricated.3 The latter has been defined as a device ‘used for transferring to an articulator the contacts of anterior teeth when determining their influence on border movements of the mandible’, and can be used to copy the occlusal prescription and features of the guiding surfaces, thereby preserving the desired dynamic occlusal scheme.17 The technical stages involved with the fabrication of the latter device in summary (Figures 3, 4, 5 and 6) include:3

Following the fabrication of a guidance table, the diagnostic cast is replaced with the working cast and the ICP mounting is confirmed. The guidance table now enables the technician to replicate the functional aspects to be replicated into the new restorations.

Finally, when planning the making of multiple indirect posterior teeth restorations, which may also be involved in providing mandibular guidance (with group function), it would be appropriate to attain a facebow record, a record of the ICP following the process to completing the preparations, as well as lateral and protrusive records (as described in Part 2), to permit the setting of the location of the superior and medial walls of the articulator crudely to simulate the fossa anatomy, as per the records attained. However, concerns with the accuracy of the taking of lateral and protrusive records have been expressed in the literature, with one study reporting duplicity at the level of the articulator to occur amongst approximately 73% of intra-oral protrusive and 81% of intra-oral laterotrusive articulator contacts for up to 4 mm of movement, with another study documenting concerns with the limits to the ability of the articulator to reproduce excursive tooth contacts.18, 19

Indeed, the risk of further errors and inconsistences likely to be introduced, during the process of the mounting of dental cast and the programming of the articulator, has resulted in some debate concerning the actual merits of using a sophisticated adjustable articulator over that of a more simplistic design (in relation to the final clinical/functional outcome).20

The management of a posterior tooth carrying the first point of contact in CR − the RCP

When the mandible is closed in the retruded arc of closure the first point of tooth contact is referred to as the Retruded Contact Position (RCP). A clinical decision will have to be made as to whether to replicate this contact on the indirect restoration. Consideration needs to be given to the material choice in these circumstances so as to optimize the load-bearing capacity of the material if this contact was to be replicated. If it has been decided that this contact will be replicated in the restoration then, prior to the reduction of the tooth, the upper and lower dental casts for the patient are mounted onto a semi-adjustable articulator using a facebow and retruded (CR) arc of closure records. The pin of the articulator is loosened and the RCP is identified. Starting from this position, an anterior guidance table is fabricated as described earlier. The teeth are brought forward into contact in the intercuspal position, and then the lateral movements are made in order to fabricate the guidance table. Once this has been achieved, the working cast can be mounted onto the articulator and the indirect cast restoration fabricated using the prescription as outlined by the customized guidance table.

How and when to adopt a re-organized approach towards restorative rehabilitation

According to Eliyas and Martin, a re-organized approach ‘requires the restoration of worn teeth in centric relation (CR) with an increase in OVD’.4 The re-organized approach to the restorative rehabilitation is therefore most likely to be prescribed for patients:

Whilst the second approach may permit the application of a conformative protocol, in general it is not advocated as the initial mode of treatment,22 especially given the recent advances in adhesive dentistry, clinical occlusion, available dental materials and, of course, the established biological consequences of undertaking invasive tooth preparations (especially amongst teeth that have sustained, in some cases, severe loss of tooth tissue). A conformative approach is therefore unlikely to be taken in the case of undertaking restorative rehabilitation of a worn dentition unless:

Indeed, given the scale of TW affecting western populations, 23 it is worthwhile considering the protocol for undertaking the re-organized approach for the restorative rehabilitation of a patient with TW. This protocol can be equally well applied to other circumstances where an analogous approach is advocated. In general, the process would involve (Figures 7–11):

In summary, the above protocol would aim to achieve an outcome whereby RCP and ICP would be co-incident. Hopefully, it will now also be apparent that, in essence, the only clear difference between the conformative approach and the re-organized approach (from the point of technical execution) is that the latter requires some additional stages of planning and design before providing the definitive restorations, by using techniques to conform to the newly prescribed occlusal scheme that would have been determined by the careful use of techniques that permit adjustment by relative ease.3

In relation to the re-organized occlusal scheme, it is worthwhile noting the observations of Celenza, where it has been shown that, with time, the slide from ICP to RCP will re-establish with a period of 2−12 years (possibly due to the effect of condylar remodelling, neuromuscular adaptation as well as the progressive wear of the restorative materials).29 This may perhaps challenge the need to be ‘absolute’ when trying to restore to a precise mandibular position − hence that of CR. The latter is perhaps further supported by the plethora of possible errors that may occur when trying to locate and record CR accurately (inclusive of impression-taking, casting, taking occlusal records, during the process of mounting the casts as per the records attained and by the limitations of the design of articulator used), whereby the perceived location of CR may in fact be inaccurate.20 Indeed, the capacity of the patient to adapt to the changes implemented perhaps has a very important role24 which, as discussed below, may to some extent challenge many of the traditionally held concepts in relation to clinical occlusion.

The placement of dental restorations in ‘supra-occlusion’: the ‘Dahl Concept’

As discussed above, for the majority of patients, tooth wear is accompanied by dento-alveolar compensation.21 The latter is a form of physiological compensatory mechanism that allows occlusal contacts to be maintained despite the process of tooth tissue loss in order to attempt to preserve the efficacy of the masticatory system. It is probable that adaptation at the neuro-muscular level will also allow patients to accept their ‘new’ intercuspal positions.

The process of dento-alveolar compensation does, however, lead to the loss of the inter-occlusal space (that would otherwise exist due to the loss of tooth tissue), and thereby present a technical challenge from a restorative perspective in relation to the provision of space to accommodate the chosen restorative material.

Historically, prosthodontic protocols for the restorative management of TW would have involved the need to undertake irreversible tooth reduction in order to create the space required to accommodate conventionally retained crown and onlay restorations/restorative materials. However, it has been well documented that the preparation of teeth to receive full coverage indirect restoration may culminate in not only the irreversible loss of pulp vitality, but also the marked loss of coronal volume.30, 31

Whilst, in some cases of TW, the required inter-occlusal clearance can be attained by adopting a re-organized approach toward the rehabilitative process (by utilizing the discrepancy between RCP and ICP as discussed above), this approach may, unfortunately, culminate in several teeth (often teeth unaffected/relatively unaffected by TW) being in need of restorations in order to maintain occlusal stability. It will also increase the overall level of complexity of care, as well as the longer-term maintenance requirements and treatment cost. Under such circumstances, where there is a need to avoid subtractive tooth preparations, one possible option can be the placement of restorations in a supra-occlusal position; a concept commonly referred to as the Dahl Concept/Dahl Phenomenon and is now commonly utilized for the restoration of patients presenting with localized TW (Figures 14−18).32, 33

It has been reported that, in most cases, following the process of placing a supra-occlusal restoration, re-establishment of occlusal contacts usually occurs within 4−6 months. However, it may sometimes take up to a period of 18−24 months.34

The actual Dahl concept refers to the relative axial tooth movement that is observed to occur when a localized appliance or localized restoration(s) are placed in supra-occlusion and the occlusion re-establishes full arch contacts over a period of time. The concept is thought to occur through a process of controlled intrusion and extrusion of the dento-alveolar segments. Indeed, it was reported by Dahl and Krungstad33 that the inter-occlusal space created occurs through a process of combined intrusion (40%) and extrusion (60%). It has also been suggested by Hemmings et al that an element of mandibular repositioning involving the condyles may also be occurring concomitantly.35 Other phrases used to describe the latter concept include ‘minor axial tooth movement’, ‘fixed orthodontic intrusion’, ‘localized inter-occlusal space creation’ or ‘relative axial tooth movement’. The same principle may be extended to the controlled movement of posterior teeth to create space.34

According to a review by Poyser et al, when considering the studies that have assessed the efficacy of the Dahl concept, a success rate of between 94−100% has been reported; furthermore, the level of space creation appears to be consistent, irrespective of age and sex.34 However, it would appear as if careful case selection with the placement of restorations in the supra-occcusal position is of paramount importance when aiming for a successful outcome with the application of this concept.

Hemmings et al have reported that failures also occur in patients with gross Class III malocclusions, with mandibular facial asymmetry or with a lack of stable occlusal contacts in either ICP or CR.35 The lack of eruptive potential should also be given due consideration. Patients who may display reduced eruptive potential (and may not be suitable for this form of intervention), include those presenting with:

The application of the Dahl concept should also be undertaken with great caution amongst patients who may have/had:

Whilst there is little evidence in literature to suggest that the process of controlled intrusion and extrusion is associated with possible adverse effects, such as pulpal symptoms, periodontal problems, TMJ dysfunction symptoms and apical root resorption,34 the feature of compliance with removable appliances to achieve intra-occlusal clearance (as per the original appliances used) has been identified as a true concern. To overcome the issues related to patient compliance (as well as the aesthetic concerns of the removable prosthesis with visible clasp display), an alternative approach involving the provision of a fixed metal prosthesis cemented in supra-occlusion, with the same occlusal prescription as with the removable appliance, has been proposed.36 With the subsequent establishment of inter-occlusal clearance, the objective of the treatment plan was to replace the casting with conventional indirect castings.

The removal of the metallic backings may, however, occur at a risk of further compromising an already brittle, worn tooth. Furthermore, the preparation of such teeth to receive conventional restorations may have a negative impact on the pulpal status and the quantity of remaining dental hard tissue. However, as material technology has continued to evolve, it has now become acceptable to use tooth-coloured materials, such as resin composite, on the affected surfaces as a substitute for adhesively retained metal backings. Such composite restorations may be considered to be medium term restorations (particularly where the wear is largely from erosive causes), and may offer a suitable means of restoring (especially the worn anterior dentition) by minimal intervention, concomitantly offering a satisfactory aesthetic outcome with the scope of contingency planning.

In relation to occlusal planning, as discussed in Part 2, when attempting to treat a number of teeth (such as the anterior maxillary sextant) using the approach of placing restorations in the supra-occlusal position, it would be appropriate to mount a set of diagnostic casts in CR, and fabricate wax-ups to meet the aesthetic needs of the patient, as well as an occlusal end-point which should ideally conform to the mechanical ideal as discussed in Part 1.

The concept of placing restorations in supra-occlusion is not only limited to the management of the patient presenting with anterior tooth wear. The concept may be equally as well applied to the:

Summary and Conclusions

It is important for the dental practitioner to be aware of the traditional protocols that are recommended when undertaking restorative rehabilitation. When faced with more challenging situations, it is relevant for the clinician to be aware of the nature of the treatment likely to be required and, where this may be beyond the scope of their practice, to consider the option of referral to a colleague.

Whilst the advances in knowledge (especially in relation to the potential for adaptability in response to planned occlusal changes) are to some extent altering the way in which the subject of clinical occlusion may be pragmatically approached, it is important, when prescribing treatments that may involve the placement of restorations in the supra-occlusal position, that a careful patient assessment is carried out, valid informed consent is gained and the patient is closely monitored post-treatment.