References

Principles of orthognathic management of dentofacial discrepancies

From Volume 45, Issue 11, December 2018 | Pages 1048-1056

Article

Individuals with severe dentofacial discrepancies, beyond the scope of conventional orthodontic treatment (ie orthodontic camouflage), will often require a joint orthodontic-surgical approach to managing their malocclusion.1 This treatment approach, involving a combination of orthodontic treatment with orthognathic surgery, is used to manage severe underlying skeletal and dental discrepancies in the anterior-posterior (AP) (such as severe Class II or Class III malocclusions), vertical (such as anterior open bites and deep overbites) and transverse dimensions (usually involving facial asymmetries and severe crossbites/scissors bites).1 Treatment of this nature is usually started when facial growth has slowed, and timed such that the pre-surgical orthodontics have been completed and patients are ready for surgery, when their growth is significantly reduced or stopped, usually at about 17−18 years in females and over 18−19 years in males.2 However, it is prudent for orthodontists to assess each patient individually, sometimes with growth charts, as growth patterns vary and these timings may not be correct for all patients.2

Indications for orthognathic treatment

As orthognathic surgery is largely an elective process, it is imperative to determine the patients' presenting concerns, their motivation towards seeking treatment, and the realism of their expectations from treatment. These usually fall into the categories mentioned below.3 In addition, the recent introduction of the Index of Orthognathic Functional Treatment Need (IOFTN) has been shown to be a useful tool to help assess and prioritize treatment to patients requiring orthognathic treatment including:4

Psychological influences

Several studies5, 6 have demonstrated that facial anomalies, including those that are minor, can result in negative public responses, which may include bullying, teasing and reduced social acceptance. Such an impact can often result in a severe social handicap, inhibiting an individual's normal functioning within society.3, 7 In addition, in modern society it is generally observed that dentofacial aesthetics play an important role in personal, work and social situations.3, 7 Therefore, improvement in dentofacial aesthetics is an important motivating factor for many patients seeking orthognathic treatment. There are, however, situations where underlying psychopathologies, such as dysmorphophobias (eg Body Dysmorphic Disorder), are a driving factor in patients seeking aesthetic or cosmetic treatment. Care must be taken to identify such patients and appropriate psychiatric referrals should be made as surgical treatment is unlikely to result in patient satisfaction.8

Masticatory and other functional problems

Patients with facial deformities exhibit varying degrees of masticatory efficiency which differ from the normal population.9 These differences may present as difficulty with incising food and/or difficulty with mastication as a result of a limited number of occlusal contacts or interferences.9 In contrast, some individuals may have gingival or palatal soft tissue trauma due to a deep overbite or excessive tooth attrition. These are some of the factors that motivate patients to seek orthognathic treatment. Some patients may seek treatment as a result of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction and/or speech problems. However, there is little and mostly weak evidence to show that this type of treatment may alleviate TMJ problems.10, 11 In fact, it is important to note that orthognathic surgery can have adverse effects on the TMJ in previously asymptomatic patients, with the prevalence varying from 4%−12%.10 The evidence for speech is more controversial,12 though clinical evidence may suggest that, in some patients, their speech may improve following orthognathic treatment. If speech improvement is sought by patients, it is important that they are assessed by a speech and language therapist to determine the likelihood that speech may improve following correction of the malocclusion. In some cases, orthognathic surgery may help to expand the airway and help relieve obstructive sleep apnoea. It is important that patients undergo a sleep study and are seen by a respiratory sleep physician to determine the possible benefits of surgery at the planning stages.

Factors to consider prior to embarking on orthognathic surgery

In addition to the orthodontic considerations and the extent of the facial deformity, other factors also need to be considered when treatment planning and assessing the feasibility of treatment. These include factors such as:

Dental health

It is imperative that patients have good periodontal health prior to embarking on any treatment. Fixed appliances may act as stagnation points, making oral care very difficult. Therefore, patients must have immaculate oral hygiene prior to and during orthodontic treatment. In addition, the patients' predisposition to periodontal problems (eg ‘periodontal biotype’) should be assessed. Thin tissue periodontal biotypes are delicate and respond differently to inflammation and trauma compared to thick tissue biotypes, as the underlying labial bone tends to be thin.13 Therefore, careful consideration with orthodontic mechanics should be made when assessing the periodontal tissues, especially with thin tissue biotypes. Any active periodontal disease must be resolved as it is likely to worsen during treatment. Finally, the dentition must be caries free. Any potential carious lesions must be investigated and restored by the GDP.

Psychosocial aspects

In addition to the psychological issues mentioned above, it is important to consider the psychosocial aspects of a patient with facial deformity. The patients' ‘external motivation’, ie motives based on the perception of others through social or professional interactions on their image and identity, is important to understand.14, 15 This cohort of patients will require more psychological support and exploration of their concerns prior to embarking on any intervention.14 In contrast, patients that have internal motivations, ie those not influenced by their peers, are more suitable for intervention.14, 15 Some patients are able to cope with a change in their appearance post-surgery, whereas a small cohort may not and it is this group that must be recognized in order to provide adequate support post-treatment.

Anatomical considerations

This is especially important when considering orthognathic surgery in patients with cleft lip and palate and some with true craniofacial deformities. In the case of maxillary advancement, there is a risk that this could increase the nasopharyngeal space, impairing the velopharyngeal mechanism, resulting in velophayngeal insufficiency.16 This can result in worsening of hypernasality of speech. Careful planning and assessment by the speech and language team is necessary prior to considering this treatment.17

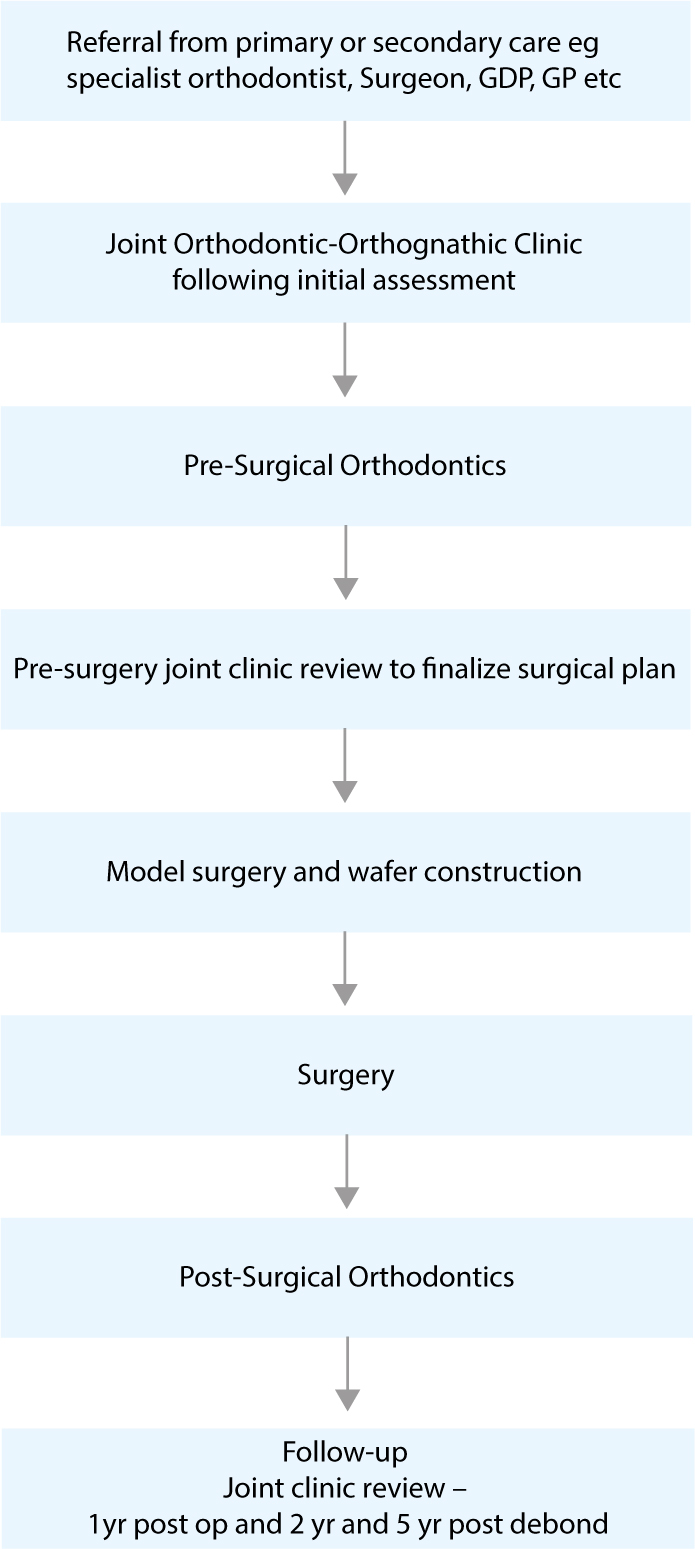

Joint orthodontic-orthognathic treatment pathway

A collaborative approach, which is usually in the form of a multidisciplinary team (MDT), is required to ensure effective treatment planning and execution, in order to have successful outcomes when managing patients undergoing orthognathic treatment.18 The MDT clinic will include the orthodontist, the oral and maxillofacial surgeon, ideally a clinical psychologist/liaison psychiatrist and a clinical nurse co-ordinator.1 The expertise of the GDP may be required to manage caries, periodontal disease, tooth wear and missing teeth. For patients with more complex craniofacial deformities, input from other specialties, such a craniofacial surgeon and ear, nose and throat surgeon, may also be required in some situations.1 This MDT team approach ensures that the patient receives the correct treatment options, with discussion of all the risks and benefits, so that treatment is delivered with a systematic approach and there is a seamless transition of care between clinicians (Figure 1).

Multidisciplinary Team (MDT) Clinic

The MDT clinic is one of the most important stages of the orthognathic pathway. It is where all the experts within their respective field meet and devise a holistic plan/approach to manage patient needs and help ensure a seamless flow of patient care between specialties. The patients' psychological factors and presenting concerns motivating treatment should be identified at this clinic.1 An informed discussion of the potential treatment options and the feasibility of this treatment addressing, in particular, patient concerns, can then be discussed in principle. This is important in managing patients' expectations, and an assessment by the liaison psychiatrist can be planned at this visit should there be concerns about managing unrealistic expectations from treatment and to deal with the facial changes that can occur. The patient should also be counselled on the sequence of treatment, both orthodontic and surgical, duration of treatment and alteration to lifestyle immediately post-treatment until full recovery.18 Finally, changes in mood post-surgery, which can include a feeling of ‘being low’ and depression, should also be discussed at length.18 This typically lasts a few days post-operatively, however, in some cases where there is difficulty in acceptance of changes to facial appearance, the importance of providing adequate support during this period by family, friends and clinicians should be highlighted.18 Further professional psychological support should be arranged for this cohort of patients.18 Once the patient concerns have been identified, a clear and concise plan should be devised to address these. In addition, further investigations, such as CBCT scans to assess skeletal asymmetries, or occasionally isotope scans, can also be useful for comprehensive assessment.

Computerized prediction software can be used to illustrate the potential facial changes in profile, which may be helpful in allowing the patient to visualize the proposed plan. The software generally uses a mathematical algorithm, based upon average data, to predict soft tissue changes following hard tissue movement.19 Because of potential errors, such software should be used with care and patients should be made aware of the limitations of predictions based upon average data.1, 19

Treatment prior to commencement of orthodontic treatment for stabilization of dental health is where the GDP can play a vital role. Regular dental review by the GDP and hygienist throughout the treatment pathway is essential to maintain dental and periodontal health. On occasions, patients may seek the advice of the GDP about whether or not they should embark upon treatment.

Risks of surgery

Surgical complications are dependent upon the surgical procedure but normally include general anaesthesia risks, pain, oedema, bleeding, temporary or permanent neurosensory deficit of the lips, chin, cheeks, tongue, palate and gingivae. It has been reported that facial oedema can take at least six months to settle fully, so the final facial aesthetic outcome cannot be assessed until this has occurred.20 Neurosensory deficit can vary depending on the surgical site. With mandibular bilateral sagittal split osteotomy (BSSO) paraesthesia of the lower lip is the most common complication. The prevalence varies from 9%−85% and appears to be affected by age.21, 22 It has been reported that the prevalence of altered sensation between the ages of 18−31 years is approximately 17%, whereas patients greater than 31 years of age have the highest prevalence of altered sensation, of approximately 29%.21, 22 Furthermore, this complication also increases if a bilateral sagittal split osteotomy (BSSO) is carried out in combination with a genioplasty.21 The prevalence of plate infection following a Le Fort I osteotomy is uncommon, at approximately 1.4%.23 However, the prevalence of plate infection following a bilateral sagittal split osteotomy over two years is thought to be approximately 16%.24 If the latter complication occurs, the plate will often have to be removed under a short general anaesthetic.

Pre-surgical orthodontics

Pre-surgical orthodontic treatment usually takes approximately 9−24 months, whereas post-surgical orthodontics can vary between approximately 4−12 months.25, 26

Orthodontics plays an integral part in preparing the patient for orthognathic surgery. It is important to plan this treatment in all three planes of space; anteroposterior, vertical and transverse. Pre-surgical orthodontics essentially involves the following phases:

Relief of crowding and alignment

Relief of crowding can be carried out either by arch expansion, increasing the arch length, interproximal enamel reduction, or dental extractions. Carrying out a space analysis will help with determining the amount of space required to correct the crowding and for incisor decompensation. In surgical patients all of these factors must be carefully considered, depending on the type of malocclusion and the types of surgical moves required. These are usually planned when the patient attends the initial MDT clinic. In a Class III patient, for example, crowding in the lower arch, if mild, can be addressed by proclining the lower labial segment, thereby decompensating the incisors. In the maxillary arch, however, crowding can be addressed with either arch expansion, in the presence of mild crowding, or extractions, if the crowding is moderate to severe. Both will allow for retraction of the maxillary incisors, in turn decompensating them to their ideal position. This allows for maximal surgical moves to be achieved in correcting the malocclusion.

Decompensation

In the presence of a skeletal discrepancy, the incisors tend to compensate for the malocclusion by proclining or retroclining towards each other (dento-alveolar compensation), if the soft tissue environment is favourable and, in some cases, this can camouflage the extent of the malocclusion. For example, in a Class II patient the lower incisors may be proclined, whereas in a Class III skeletal relationship it is the converse, where the lower incisors are retroclined and the upper incisors are proclined to reduce the extent of the reverse overjet.1, 3 Incisor decompensation involves correcting the inclination of the incisors to their appropriate position in relation to their respective jaw. This will often result in the malocclusion looking worse before surgery, which must be explained to the patient as part of the informed consent process (Figure 2). In some cases, it may be that partial decompensation is appropriate, for example, if there is a risk to the gingival attachment or if the size of the surgical movements needs to be reduced.

Arch co-ordination

Most patients with anteroposterior discrepancies tend to have an associated transverse discrepancy, which is usually in the form of a narrow maxilla. To assess the extent of the transverse discrepancy, the study models can be articulated by hand into the approximate proposed post-surgical occlusion, which is usually a Class I incisor and canine relationship. This helps to quantify the amount of intermolar and intercanine expansion that is required to produce an ideal interarch relationship post-operatively. Depending on the amount of expansion required, several methods can be used for this, including expansion with archwires, a Quadhelix appliance, rapid maxillary expansion (RME) or, in some cases, with severe transverse discrepancy (>5 mm) a surgically assisted rapid maxillary/palatal expansion (SARPE) procedure may be required or, alternatively, segmental maxillary surgery can be used to expand the arch. In other severe cases it may be possible to accept a bilateral posterior crossbite at the completion of treatment, however, it is important to ensure that there is no associated mandibular displacement associated with this crossbite.27

In certain malocclusions, space for interdental surgical cuts must also be created if segmental surgery is planned. To facilitate placement of temporary intermaxillary fixation and elastics during surgery, large dimension stainless steel archwires (0.019” x 0.025”) are usually ligated with steel ligatures just prior to surgery. Surgical hooks can be placed onto these archwires to allow the surgeon to place temporary intermaxillary fixation during surgery.

Following the pre-surgical orthodontic phase of treatment, a full set of records, including radiographs, such as a lateral cephalometric radiograph and an orthopantomograph, standardized facial and intra-oral photographs, study models and a wax bite in retruded contact position, are taken. These records should be made available for the pre-surgical MDT clinic.

Pre-surgical MDT clinic

In addition to re-assessing the patient clinically, the records taken as mentioned above following pre-surgical orthodontics are analysed at a joint clinic appointment to determine the final surgical movements. It is likely that the original surgical plan may alter slightly, based upon the changes that have occurred during pre-surgical orthodontics and possibly due to growth. Careful planning is required to determine the final surgical moves, which include assessing the soft tissue drape, the nasal shape and, in particular, the alar base width and nasal projection. This is especially important if a maxillary advancement and/or an impaction has been planned. Several other factors are considered as well, which include the maxillary incisal and maxillary position, mandibular and chin point position, and the final dental occlusion. These are all considered in the three planes of space.

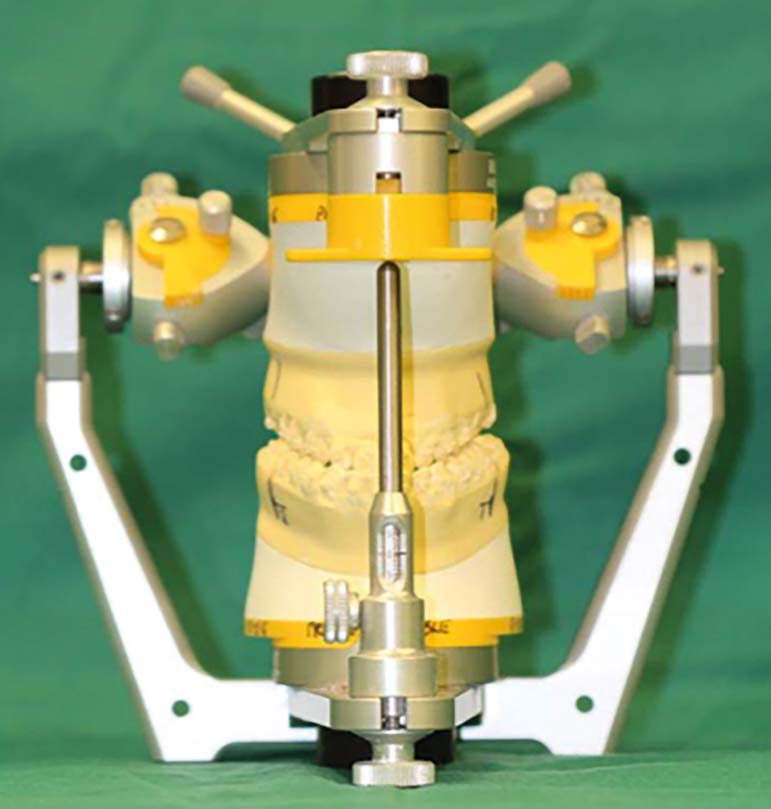

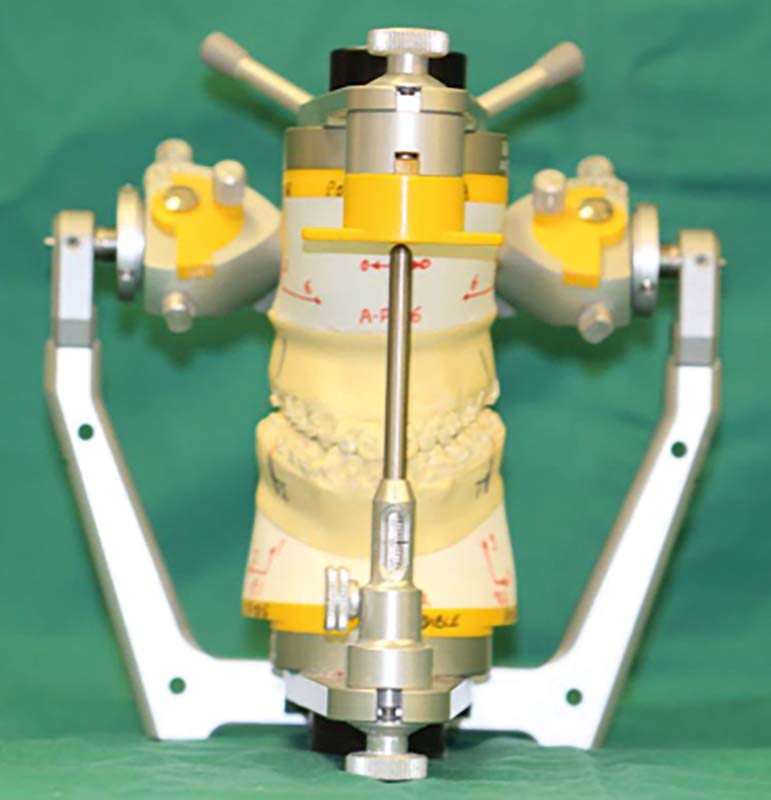

Model surgery and wafer construction

Following the pre-surgical orthodontic phase and finalization of the surgical plan, a facebow record and a waxbite in retruded contact position is taken to mount study models onto a semi-adjustable articulator. Model surgery is then carried out on the mounted models, which helps with the assessment of the extent of the moves, the final occlusal interdigitation and the effects of mandibular autorotation (Figure 3). Once the model surgery is complete, the models are then used to construct the surgical wafers which help to guide the surgeon during jaw repositioning. Usually, in Le Fort I osteotomies or mandible-only surgery, a single final wafer is required. However, in bimaxillary surgery an intermediate wafer is required to position the maxilla in relation to the pre-surgical mandibular position. A second wafer is used to relate the mandible to the new maxillary position, which will result in the final occlusion.

Surgery

The details of the surgical procedures carried out in orthognathic surgery are beyond the scope of this paper. However, Table 1 illustrates some of the most common procedures performed.19 The mandibular third molars are usually surgically removed at least six months prior to the orthognathic surgery to allow for unimpeded osteotomies. This may also be carried out at the time of surgery dependent on surgeon preference. The theory behind early extraction is to allow favourable bony healing, which may then allow for a favourable surgical split at the time of the osteotomy.28 Following the surgical procedures, the osteotomy sites are stabilized with semi-rigid fixation using titanium plates and screws which remain in situ unless complications arise, such as infection around the plates. Patients often ask if this metalwork will activate security checks at airports and they can be advised that this is unlikely to occur as titanium is a non-magnetic metal. For the same reason, the metal work is unlikely to interfere with MRI scans of the head that may be required in the future.

| Region | Procedure | Indications |

|---|---|---|

| Maxilla | Le Fort I osteotomy − most common procedure Maxilla is separated from the skull above the level of the tooth roots and mobilized and repositioned according to the surgical plan | Correction of: |

| Le Fort I segmental osteotomy − similar procedure as above but requires separation near or at the mid-palatal suture to split the maxilla into 2 halves | Correction of narrow maxilla by allowing transverse expansion | |

| 2-part maxillary osteotomy − requires Le Fort I osteotomy followed by splitting the maxilla into an anterior and a posterior segment | Correction of vertical discrepancies associated with a large step in the occlusal plane | |

| 3-part maxillary osteotomy − similar to above procedure but the posterior segment is now divided into 2 separate segments near or through the mid-palatal suture | Correction of transverse (usually posterior crossbites) and vertical discrepancies. A typical case where this technique is used is in a patient with a narrow maxilla with an anterior open bite | |

| Mandible | Bilateral sagittal split osteotomy (BSSO) − commonly performed procedure; mandible is separated vertically at the level of the ramus and body | Correction of mandibular prognathism, retrognathism and asymmetries For anticlockwise rotation of the bimaxillary complex Sometimes for the correction of smaller anterior open bites |

| Vertical subsigmoid osteotomy (VSSO) | Carried out when loss of sensation to the lower lip needs to be minimized. Allows setback of the prognathic mandible and asymmetry correction |

Post-surgical orthodontics

Following surgery, the patient is usually reviewed one day and subsequently one week post-operatively by the surgeon and the orthodontist. During these visits the occlusion is checked and assessed for any discrepancies. In some cases, the wafer may still be in situ. If this is the case, the mandible should occlude directly into the wafer without any displacement. Light or medium weight intermaxillary elastics may be used to guide the occlusion into good intercuspation. The patients are usually reviewed on a weekly basis for the first month. It is essential to try and obtain good intercuspation during this phase of treatment. Post-surgical orthodontics should usually take about 4−9 months, following which the fixed appliances are debonded and the patient provided with upper and lower orthodontic retainers, as appropriate (Figure 4). Figure 4 (i, j) shows some generalized extrinsic staining and calculus deposits caused by intake of large amounts of coffee and tea and potential difficulties with interproximal cleaning. Regular scale and polish, oral health and preventive advice from the GDP during treatment can help reduce the extent of the staining and calculus deposits. It is also important that a regular check-up is carried out by the GDP following removal of the orthodontic appliances to address the patient's oral health needs following orthognathic treatment.

Outcomes and long-term stability of orthognathic surgery

Although orthognathic treatment is an elective process that clearly results in a significant improvement in function and aesthetics, there are several risks associated with this treatment in addition to the demanding nature of the procedure for the patient.29, 30 It is therefore imperative that the planned procedures take into account the long-term stability of the final occlusion and ensure that the patient is informed from the outset about all the aspects of the treatment and potential outcomes.29, 30

The stability of the final treatment is dependent on several factors, which include the type of orthodontic tooth movement, the surgical procedure, fixation type and technique and, finally, post-treatment retention and compliance. The University of North Carolina (UNC) Dentofacial Program database has constructed a hierarchy of procedures depending on their long-term stability.29, 30 It was found that the most stable procedures were maxillary impaction and mandibular advancement (<10 mm in patients with normal face height), which had more than a 90% chance of <2 mm relapse.30 Maxillary advancement (in patients with moderate moves, <8 mm) was reported to have more than 80% chance of <2 mm relapse. The least stable were maxillary expansion, setdown and mandibular setback, which was reported to have a 40%−50% chance of a 2−4 mm post-surgical change.30 Finally, as a rule of thumb, the pterygomasseteric sling should not be stretched as this will almost certainly lead to relapse.31 Post-orthognathic condylar resorption is thought to be a long-term complication that can occur post-operatively.31 This is more common in young Caucasian females, with a pre-operative high angle Class II malocclusion requiring a mandibular advancement.31

Recall

As a routine, patients should be reviewed one year post-operatively and two years post-removal of the fixed appliances at a MDT meeting. Some providers also review patients at five years post-surgical treatment. The senior authors advise long-term review of all orthognathic surgery patients. This allows for review of the post-treatment changes and assessment of level and degree of potential relapse. It also allows for data collection and auditing of the procedures that were performed to inform patients of the risks and outcomes of treatment better in the future.

Surgery first orthognathics

In addition to detailed discussion of conventional orthognathic treatment as above, it would be sensible to discuss an alternative technique towards managing facial disharmony that is popular in South-East Asia. This technique is called the Surgery First approach and was first proposed by Brachvogel et al.32 The major driving factor to this approach was reducing the time to treat patients requiring orthognathic treatment. It has been argued that the conventional method takes much longer, especially in view of the lengthy pre-surgical orthodontic treatment.32 The main principles behind this approach are to carry out the surgery first and, subsequently, there is an increased bony turnover and blood flow in the region, thereby increasing rates of tooth movement. In addition, where appropriate, by carrying out surgery first, this avoids the need for pre-surgical orthodontics, potentially further reducing the treatment time.33

The general indications for surgery first include fairly mild malocclusion, ie mild crowding, minimal curve of Spee, minimal compensation and with little or no transverse discrepancy.33

Despite the advantages of reduced treatment time, this treatment approach requires meticulous pre-treatment planning to ensure that the jaws can be approximated correctly during surgery, as any error can be detrimental to the final outcome. The clinicians have to visualize the final position of the dentition and construct surgical wafers accordingly to guide the surgeon to place the jaws in the correct position.33, 34 Malocclusions requiring tooth extractions further increase the challenges to the planning process.34 There are clear limitations to this approach, requiring careful case selection and experienced orthodontists and surgeons to address patient concerns. It is more logical to view surgical timing in terms of the correct timing for surgery, whether ‘first’ (ie before orthodontics), ‘early’ (ie earlier than conventional timing), or conventional.35

Conclusion

Joint orthodontic-orthognathic treatment is a treatment modality that predictably allows for correction of severe dentofacial discrepancies. With orthognathic surgery there is an improvement in the patient's function, aesthetics and improved psychosocial wellbeing and therefore improved quality of life following treatment.3 It has been reported that function, aesthetics and psychosocial benefits in combination influence patient decision-making in pursuing orthognathic surgery.36, 37 It has also been reported that there is a close association between malocclusion and psychosocial function and this has been demonstrated by showing a greater improvement in psychosocial dimension scores than physical dimension scores when assessing health-related quality of life in this cohort of patients.37 Finally, the key principles to achieving good outcomes and patient satisfaction is elaborate multidisciplinary planning, appropriate psychological support and preparation of the patient, and careful post-operative care, including post-operative nutrition, wound management and post-operative orthodontic treatment. In view of the complexity and risks associated with this treatment, it is essential that a multidisciplinary team approach is utilized to ensure a seamless transition through treatment phases, reducing the risk of unwanted effects and thereby ensuring ideal clinical and patient-centred outcomes.