Article

Removable prostheses can be used alone or in combination with fixed prosthodontic treatment to manage tooth wear (TW). It is an accepted mode of treatment that can fulfil the aims of restoring the appearance, function and/or speech of patients with worn dentitions.1,2

The lack of coronal tooth tissue in cases of severe tooth surface loss can make fixed prosthodontic treatment more challenging and less predictable. Removable prosthodontic treatment may be more appropriate in these cases, especially when the additional time and cost associated with fixed prosthodontic treatment is taken into account. The remaining coronal tooth tissue can be used to support, retain and/or stabilize a removable prosthesis. A partially dentate patient with advanced tooth wear may add more credence to this form of treatment.

Patients will need to be made aware of the limitations associated with removable appliances, the added maintenance and potential risks to the remaining dentition. Patient compliance, adaptation and managing expectations will also be key to providing a successful outcome.

Indications for removable management of tooth surface loss

Contra-indications for removable management of tooth surface loss

Patients unable to tolerate a removable prosthesis.

Aims of removable management

Definitions

The following terms will be used to describe the various removable appliances:

Combinations of the above can be used on the same prosthesis.

Removable management

Severely worn teeth cannot always be restored through fixed prosthodontic means. They may be present in combination with long edentulous spans that also require soft tissue replacement. Removable prostheses can help to replace soft tissues and provide lip support. They can also be designed to have further teeth added to them in the future.

Not all teeth necessarily require replacing. Patients can function well with 10 pairs of occluding units or a second premolar to second premolar occlusion.4,5 Patients presenting with severe tooth wear often do so because it affects their anterior teeth. Compliance with removable prostheses has been shown to be better when they replace and/or restore the anterior dentition.6

Despite the benefits of removable prostheses, they can lead to increased levels of plaque accumulation when oral hygiene is inadequate.7 It is therefore critical that patients are given clear instructions on maintaining excellent oral hygiene and advised to leave their removable prostheses out at night. Failure to do so may quickly lead to failure of strategic abutment teeth and present further challenges for the patient and clinician.

Managing patient expectations

It is important for patients to have realistic expectations of removable prostheses. They must be informed of their limitations from the outset so that they do not attribute this to inadequate clinical work.

Treatment options

Extracting the remaining teeth and providing complete dentures

Patients are retaining more teeth for a longer period of time due to the increase in life expectancy, fluoride availability and improved oral hygiene practices.8 This increase in age, together with increasing expectations, means that patients often have a lower adaptive capacity and ability to manage complete dentures at an advanced age. Extracting the remaining teeth, no matter how heavily restored or worn, has therefore become a less frequently practised option. It can, however, still be a pragmatic option if there are only a few teeth remaining that are beyond saving, and if the patient is not suitable for complex treatment. Anecdotally, it is thought that many bruxist patients transform into maladaptive denture-wearing patients. The high occlusal loads lead to early mucosal trauma and ridge resorption. Careful planning and care at every stage during the process of making complete dentures will be required. An implant-supported mandibular overdenture can be considered as a further treatment option in this cohort of patients to facilitate and improve this transition.9,10 These will still be subjected to high occlusal load in bruxist patients.

Complete or partial overdentures

It can be more appropriate to reduce the teeth further when they are severely worn and provide either complete or partial overdentures. These appliances replace the worn teeth with prosthetic teeth and an acrylic flange. The following advantages can be gained from doing this:

There are, however, disadvantages associated with this treatment option that include:

Complete or partial onlay or overlay dentures

The occlusal or incisal surfaces of worn teeth can be restored with an onlay or overlay type appliance without a flange.

Onlay type appliances can be useful for moderately worn posterior teeth to restore the surfaces of these teeth and re-establish the correct occlusal vertical dimension. The occlusal surfaces can be made of a cobalt-chromium alloy and can be made to be an integral part of the denture framework to increase their durability.

The choice between an onlay or overlay design for anterior teeth will depend on the following factors:

Partial dentures in combination with adhesive or conventional fixed prosthodontics

Teeth that have not been affected by wear can be modified so that they can help to retain, support and stabilize a removable prosthesis. The following features can be considered when designing the denture:

Damaging occlusal forces on worn anterior teeth restored with adhesive or conventional crowns should be considered if the partial dentures only replace posterior teeth. Compliance with wearing dentures is reduced in this cohort of patients.22,23

Preliminary investigations

The following should be investigated in relation to providing removable prostheses for tooth wear.

Assessing the occlusal vertical dimension

Restoring the worn dentition to the correct occlusal vertical dimension will form the basis of treatment. In the absence of tooth wear the free-way space remains constant due to the continued growth and increase in anterior facial height into middle age.24,25 Tooth wear, however, leads to the continued eruption of teeth so that the free-way space remains constant and so do the proportions of the face. This is commonly known as compensated tooth wear.26,27

Non-compensated tooth wear occurs when the rate of the tooth wear is too fast for the physiological mechanisms of tooth eruption to keep up. There is therefore a resultant increase in free-way space and loss of occlusal vertical dimension.

Patients with compensated tooth wear will usually have a complete dentition and treatment with removable prostheses will rarely be indicated.1 Partially dentate patients with loss of the posterior dentition and wear affecting the anterior teeth will usually present with non-compensated tooth wear and a loss of OVD, making it necessary to provide treatment with removable prostheses. These patients will often have an unacceptable occlusal plane and the following can be used to determine the correct occlusal vertical dimension:

The recording of the OVD is usually carried out using occlusal registration rims. Edentulous patients will be less tolerant to changes in the occlusal vertical dimension than dentate patients (Figure 4).

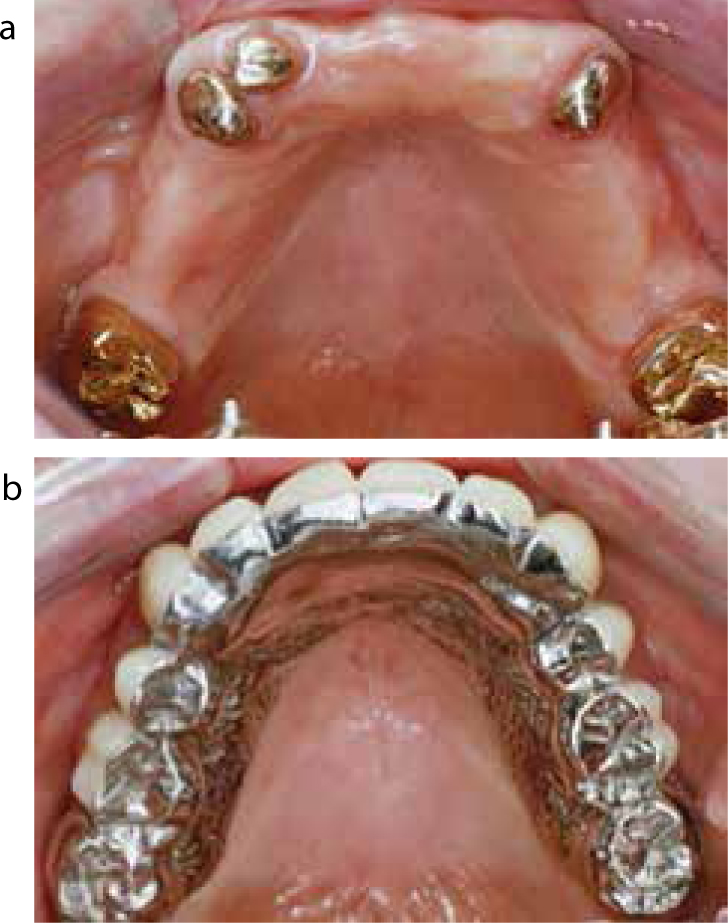

Assessing severely worn abutment teeth

As mentioned earlier, a severely worn tooth does not necessarily need to be condemned. It can be retained as an overdenture abutment. The following factors need to be considered if a tooth is to be retained as an overdenture abutment:

Assessing spaces

Spaces should be assessed in three dimensions that should include inter-occlusal, mesio-distal and bucco-palatal measurements. The following should be considered when making an assessment of the space:

Diagnostic phase

Occlusal splints

An upper, hard, heat-cured, full coverage acrylic splint with (provisional denture) or without teeth can be used in the diagnostic phase. They should provide even contact along the retruded arc of closure with anterior guidance on anterior teeth with posterior disclusion and canine guidance in lateral excursions.36 They can provide the following benefits:

Partial coverage splints should be avoided due to selective intrusion and extrusion of teeth. The resulting malocclusion can be difficult to correct.

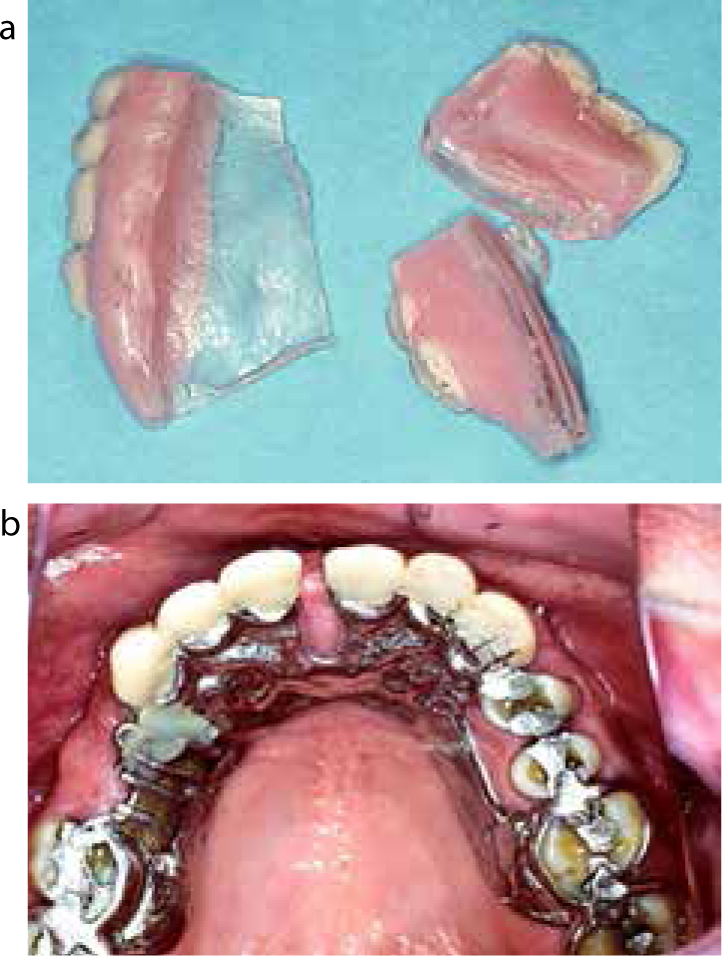

Provisional appliances

Acrylic provisional appliances that have an overdenture, onlay and/or overlay design can be provided to test changes in occlusal vertical dimension, aesthetics, phonetics and function. They can also be used to test the patient's tolerance and adaptive capacity to removable appliances. They should be designed and made with the same care as a definitive denture. They can be modified (ie relined or adjusted) whilst abutment teeth are being prepared to receive extracoronal restorations or being built-up with composite resin prior to making the definitive dentures.

Definitive dentures

The ideal features of the provisional appliance should be carried forward to the definitive denture. These include the proposed changes to the occlusal vertical dimension and aesthetics. A wax try-in will be required if any further changes are proposed.

The definitive denture should fulfil the following aims:

The definitive denture should be designed prior to considering any irreversible changes to the abutment teeth. The changes to the abutment teeth can then be made taking into account the materials to be used to construct the definitive denture. The stability of dentures and patients' adaptation to them will be increased if guidance in excursions is maintained on the natural teeth. In the depleted dentition it is more likely that a bilateral balanced occlusion should be provided.

Materials

Denture base

The retention of teeth as overdenture abutments will limit the amount of space available for the denture base and prosthetic teeth. This can therefore pose challenges when managing patients with wear.

The ideal denture base should meet the following requirements:40

Denture bases can be metal- or resin-based.

Acrylic resin bases need be at least two to three millimetres thick, can be aesthetic and easily adjusted and relined. They can, however, release internal strains that may lead to distortions and can be more prone to accumulate deposits, be bulky and less abrasion resistant.40 To counteract these shortcomings, some form of strengthening of the denture base should be considered.

Metal-based dentures that can be cast in either gold, chrome or titanium alloys are more difficult to reline and adjust. They do, however, have the following advantages:

Prosthetic teeth

The material used for replacing missing tooth tissue will be influenced by the following factors:

Materials

Materials commonly available include:

Acrylic resin

Acrylic resin prosthetic teeth need to be provided in sufficient bulk without thin or sharp edges and can be chemically bonded to the acrylic resin base or attached to a metal base through mechanical retention or chemical bonding. An adhesive containing 4-methacryloxyethyltrimellitic anhydride (4-META) can be used to bond acrylic resin to metal-based dentures. A chemical union can make the junction more hygienic. The low abrasion resistance can make this material easy to adjust but prone to accelerated wear in patients with parafunctional habits. Acrylic resin prosthetic teeth can provide a natural appearance and are the kindest material for opposing teeth.

Chrome alloy

Chrome alloy prosthetic teeth can be cast in thin section and are therefore useful when space is limited. They still provide good strength and rigidity in thin section. They can be cast as part of the overall framework but their appearance will limit their use to posterior sections of mouth and as palatal backings on anterior teeth. They can, however, be difficult to adjust and also abrasive to opposing natural teeth when they lose their surface polish. Chrome alloy prosthetic teeth can be useful for covering the worn occlusal surfaces of posterior teeth with an onlay type design in patients with parafunctional habits.

Gold alloy

Gold alloy prosthetic teeth will cause the least abrasion to natural teeth and can be more easily adjusted. Cast gold occlusal surfaces can be attached to acrylic resin teeth and can be useful in patients who parafunction. There is a high cost involved.

Ceramic

Ceramic prosthetic teeth can provide excellent aesthetics but are brittle and very abrasive once they lose their surface glaze. They can also make a clicking sound in function but can be bonded to metal-based dentures through a process of tribochemical coating.

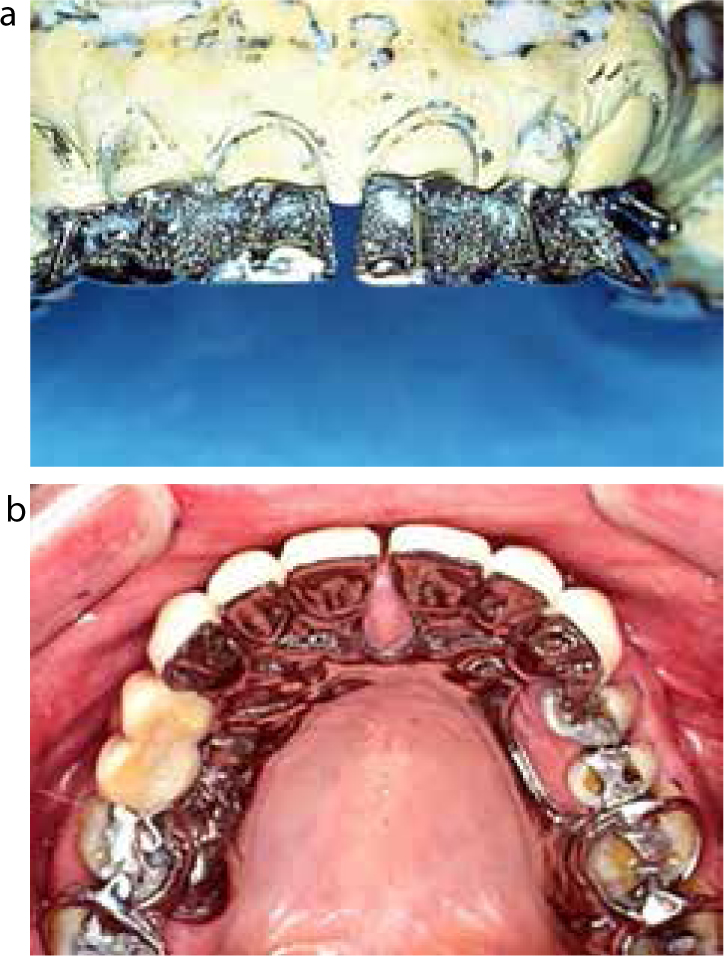

Tooth-coloured veneering materials can be the weak link in the durability of partial and complete dentures made for patients with tooth wear. Macromechanical and micromechanical retention needs to be applied to the denture design. Retentive beads, ‘nail heads’ and struts can be combined with palatal metal backings to protect acrylic, composite or porcelain components. On occasion, these backings or onlays need to be extended up to the incisal edge or occlusal contacting surfaces (Figure 5).

Maintenance

The cohort of patients treated with removable prostheses for worn teeth are usually older and have a number of other missing teeth. These have often been lost as a result of plaque-associated disease and so these patients are often at high risk of caries and periodontal disease. This is often compounded by diminished fine motor skills so that cleaning may still be ineffective, even if patients are motivated. Plaque accumulation will also tend to increase in the presence of removable prostheses.7 These patients must therefore be managed similarly to patients with a high caries risk.41

It is therefore of utmost importance that patients change their behaviours in order to prolong the survival of their abutment teeth. Patients should be instructed to do the following:

An occlusal splint with or without replacement teeth can be made for the patient to be worn at night to protect the abutment teeth from parafunction. If the denture design has not been robust, early failures should be expected (Figure 6).

All of the above should be supplemented with regular recall as appropriate to review the abutment teeth, soft tissues and removable prostheses (Figure 7).

Maintenance care

By definition patients treated for tooth wear are heavily restored and need more frequent review and maintenance care. Dental caries and periodontal disease can be worsened by the placement of multiple restorations or by using an overdenture. Preventive and periodontal care with a reliable recall system will help with preventing primary disease.

Biomechanical failures should also be expected and the patient informed of this. If their teeth have been worn down or fractured, patients will exert the same forces on their restorations. If a patient is prepared to use an occlusal splint on a regular basis, adverse events can be reduced. Furthermore, well designed and executed prosthodontics can give these patients a welcome break from the restorative spiral downwards with the loss of restorations and teeth.

Concluding remarks

Dentists will be treating more patients with tooth wear as the population ages. There are many challenges ahead for the dental team in providing high quality dentistry for these patients. There have been many technological improvements over the years to help with providing care. As a profession we will need to continue to develop new techniques to deliver cost-effective and successful treatments for our patients.

Key Points

Endnotes

The British Society for Restorative Dentistry hopes that these guidelines will act as a practical reminder of the standards that the BSRD tries to achieve. Any comments you may have will be gratefully received and should be addressed to the Honorary Secretary.