Article

Tooth wear (TW) is a common condition affecting patients who often require advice and treatment from dentists. Physiological TW is normal and accepted by most patients. Pathological TW, by virtue of symptoms or rapid wear, will prompt the need for dental care. It can range from mild sensitivity from an abrasion lesion to gross destruction of the dentition. Similarly, treatment can range from simple operative care to full mouth reconstruction with crowns or complex dentures. Too little or too much treatment can lead to tooth loss and patient complaints.

These guidelines are designed to help dentists manage tooth wear. A selected literature review covers three sections:

Each section is concluded with a summary of key points which can act as a quick reference checklist for the busy practitioner. It is hoped that effective treatment or advice given at the right time can reduce the amount of long-term maintenance care required in the future. However, it is acknowledged that some severe bruxist patients will always require regular repairs or replacement restorations.

Guidelines become out of date immediately they are published. The society will review and update these guidelines on a 3-yearly basis. The work that the authors have put in to draft these guidelines is gratefully received. The British Society of Restorative Dentistry (BSRD) Council and members of the society are also thanked for their comments in improving the document. Effective treatment does exist and it is most gratifying to make a dramatic difference to patients with tooth wear when guidance is provided.

Definition

Tooth wear, or as it is also often referred to as non-carious tooth surface loss (TSL), can be described simply as ‘the pathological non-carious loss of tooth tissue’.1

The distinction between pathological and physiological TW can be difficult to determine. Wearing of the teeth is a normal physiological process. The estimated normal vertical loss of enamel from physiological wear is thought to be approximately 20–38 μm per annum.2 It is important to remember that just because a tooth has some element of wear this does not always necessitate treatment. Tooth wear may be regarded as pathological if the rate of wear is greater than that expected for the patient's age, the patient has concerns over the wear or the prognosis of the tooth is compromised due to the wear.

Tooth wear is often multifactorial in nature and can be difficult to distinguish between, but it is often subdivided into:

Attrition

‘The loss of tooth substance or a restoration as a result of mastication or contact between occluding surfaces of approximal surfaces’.1

Erosion

‘The loss of tooth tissue by chemical processes not involving bacterial action’.3

Abrasion

‘The physical wear caused by materials other than tooth contact’.4

Abfraction

‘Tooth wear located in the cervical area caused by flexural forces during function and parafunction’.5

Prevalence

Prevalence in children and adolescents

Epidemiological research across Europe has shown an increasing prevalence in tooth wear in children over the last ten years. An increased level of TW is found to be associated with increasing age, especially in the deciduous dentition.6 Tooth wear was reported to be between 0% and 80% for children under seven years of age. This significant relationship of level of TW to increase in age found in the deciduous dentition did not appear to correspond to the permanent dentition.6

In the UK, the Child Dental Health Survey has been undertaken decennially since 1973. The most recent survey, in 2013, showed an increased incidence of tooth wear. In children aged five, 33% had some evidence of TW on the buccal surfaces, with 4% involving the dentine or pulp and 57% on the lingual, with 16% involving the dentine or pulp.7 In the permanent dentition, 31% of 15-year-olds showed signs of TW on the occlusal surfaces of the first permanent molars and 44% on the palatal surfaces of the maxillary incisors.8

Prevalence in adults

In the UK, NHS Information Centre commission surveys are undertaken decennially to assess the dental health status of adults to capture trends over time. The most recent survey, in 2009, showed an increased incident of tooth wear from 66% to 76% since the 1998 survey. Tooth wear into dentine was found to be higher than previously, at 77% in the anterior teeth. Moderate TW (extensive into dentine) also showed an increase from 11% in 1998 to 15%. Severe wear (exposing secondary dentine) remained at 2%.9

Tooth wear in adults is a common clinical finding, with an increase in prevalence with increased age. A systematic review showed 3% of 20-year-olds and 17% of 70-year-olds exhibited severe tooth wear.10 Furthermore, it has been suggested that males tend to experience greater TW than females, possibly due to increased tooth retention and greater occlusal forces in males.11

It is worth noting that prevalence studies are somewhat lacking for adults and stricter guidelines are required for quality control.10 This may be attributed to the difficulties in recruiting participants and maintaining them, the varied study designs and terminology making comparisons difficult.

Aetiology

Clinical presentation and aetiology is usually subdivided into the previously mentioned terms of attrition, erosion, abrasion and abfraction. Diagnosis is often based on the clinical findings, which may suggest one causative factor. However, it is well known that the cause of tooth wear is multifactorial, making clinical diagnosis difficult. Thus it is suggested that these single terms, which can be useful when considering and describing the aetiology, may only describe the outcome of a number of underlying events rather than the cause or process involved in the wear.

It is important to acknowledge, even if one single contributing factor appears to be involved, that other damaging factors may be present. Failure to acknowledge this may lead to insufficient advice, failure of treatment and progression of the condition. A thorough patient history is essential to help aid understanding of the causative factors.

Occasionally, patients may have inherited dental conditions that may increase the severity of tooth wear, such as dentinogenesis imperfecta and dentine dysplasia, to name but two. It is important to inform these patients of their increased risk of wear.12

Attrition

Smith and Knight13 found attrition to be the predominant pathological cause of tooth wear in 11% of cases and reckoned that it accounted for two-thirds of the combined aetiology of TW. It is important to acknowledge that a level of TW is normal, physiologically increasing with age, but may become pathologically secondary to a parafunctional habit.14 The diagnosis of parafunctional activity is difficult and patients themselves are often not aware of the condition. In fact, it has been suggested that only half of the population of bruxists are aware of the condition.15, 16 Owing to this, the reported prevalence of bruxism varies between 5% and 96%.3 Two popular theories have been proposed, but not confirmed, as the cause of bruxism, including parafunctional activity as a manifestation of stress17 and as a result of premature contacts on mandibular movement.18

At present, there is little evidence to support the theory that a reduced number of occluding teeth leads to increased tooth wear. Studies have reported no significant correlation between the loss of posterior teeth and anterior TW, including the shortened dental arch.19, 20It is suggested that the proprioceptive feedback mechanism and mutually protected occlusion contribute to this finding.19, 21

Erosion

It has been well documented that demineralization of dental hard tissue leading to dental erosion occurs following the drop in pH of the oral cavity below critical pH, ie 5–5.5.22 Smith and Knight13 found an erosive aetiology as part of the cause in almost 89% of patients referred for severe wear. Erosion is often subcategorized into ‘extrinsic’ or ‘intrinsic’, depending on the nature of the acidic causative agent.23

A wide range of diseases and syndromes are associated with erosion:

It has been noted that, for children of all socio-economic backgrounds, tooth wear is most common on the palatal surfaces of the maxillary incisors. Furthermore, cross-sectional studies report a high prevalence of erosion, 53%26 and 77%27 in adolescents and adults, respectively, in the UK. The prevalence of dental erosion in children and adolescents is believed to be due to the increased susceptibility of demineralization of the newly formed dentition, the time taken for maturation and the reduced salivary buffering capacity at night.

Extrinsic erosion

Extrinsic sources of acid may include acidic food and drinks and medications, from the environment or industrial processes. Medications, such as Aspirin (a salicylic acid), iron tonics, chewable vitamin C and replacement hydrochloric acid, may lead to erosive tooth wear.3

Epidemiological studies have observed a correlation between acidic diets and the development of erosive TW.28, 29 Acidic food and drink intake has increased on a population level, furthermore, there has been an increase in population trends of leading a healthy lifestyle with increased consumption of diet drinks and ‘juicing’, leading to increased erosion. A strong link between the increased consumption of carbonated drinks, citrus fruits, fruit juices, herbal tea and erosion is well known.23, 28, 30 Both carbonated and non-carbonated drinks exhibit a similar erosive potential.31, 32 The acids commonly found in these foods include phosphoric, citric and malic acid, however, there are many other acids with erosive potential in food. It has been accepted that titratable acidity, which is a measurement of the total acid content, is a more important indicator than actual pH value in determining erosive potential of beverages.22

Exposure to acid in the work place can lead to environmental erosion. It has been reported in those working in industries such as wine tasting33 and manufacturing battery acid.34 Leisure activities, such as swimming, may also be a causative agent due to low pH gas-chlorinated swimming pool water.35 Due to this, improvements in health and safety have been developed, such as wearing protective airways masks, to reduce the effects of environmental erosion from the work place.36

Chronic alcoholism is a source of both extrinsic and intrinsic dental erosion, Extrinsically, the alcohol consumed has an acidic component, resulting in erosion alongside the effects of regurgitation, vomiting and gastritis.4

Intrinsic erosion

Intrinsic erosion results from the gastric content entering the oral cavity.25 This can be from a variety of voluntary or involuntary habits and diseases. Vomiting can be both voluntary and involuntary as a result of pregnancy, as a side-effect of some medications, through alcoholism, alimentary tract disorders, as well as psychosomatic conditions including eating disorders.

Involuntary regurgitation of gastric acids may be a result of gastrointestinal disturbances, such as during pregnancy, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), vomiting, hiatus hernia or rumination.

Approximately half of patients with localized anterior tooth wear report having gastric reflux. GORD results in gastric content moving from the stomach into the oesophagus due to a laxity in the lower oesophageal sphincter.37 It is now recognized as a more common condition for children/adolescents than previously thought. Stomach acid has a pH of approximately 2, which is highly erosive to the dentition. The effect can be particularly damaging to the dentition, especially the palatal surfaces, when continual episodes are involved.38 Silent reflux can occur whereby patients are unaware of having longstanding, asymptomatic GORD leading to dental erosion. Referral to a general medical practitioner to assess this may be beneficial to the patient as repeated soft tissue harm can lead to strictures, ulceration of the oesophageal lining and, in some cases, malignant changes, in particular Barrett's oesophagus.39

Voluntary regurgitation is increasing due to increasing incidence of eating disorders, such as bulimia and anorexia nervosa. The most common sign of this condition is perimolysis lesions, which are erosive lesions on the palatal surfaces of maxillary incisors.40 The effects of such disorders leading to self-induced vomiting in the development of dental erosion are well documented.41, 42 The incidence of bulimia has rapidly increased, with 14 per 100,000 affected and approximately 7 per 100,000 individuals in the population now thought to be affected by anorexia. This increase may be due to increased exposure to the media portraying the ‘ideal’ body shape and size.43, 44 It is worth noting that the male to female ratio is approximately 1:10. However, males are less likely to seek medical attention so may be at equal risk of eating disorders.45

Rumination predominately affects patients with mental disabilities. It involves GORD combined with voluntary or involuntary regurgitation of swallowed food into the oral cavity, which is then re-chewed and re-swallowed. Unfortunately, this condition is poorly understood and the prevalence of erosion associated is not fully known.42

Abrasion

The prevalence of abrasion is reported in a range from 5%–85%, depending on the inclusion criteria.46 Abrasion can often result from over enthusiastic toothbrushing with abrasive toothpastes, improper use of interdental cleaning aids, or patient habits such as nail-biting, pen-chewing or having a tongue piercing. It is also suggested that there is an occupational hazard associated with some jobs, such as dress-making, glassblowers and musicians.14 Dental treatment may cause attrition if improper materials are utilized, for example, unpolished ceramic restorations against a natural tooth.1

It has also been highlighted that the present day ‘healthy diets’ may be contributing to an increase in tooth wear,1 especially if there is high erosive content from ‘juicing’, alongside an increase in abrasive foods such as nuts and seeds. It is important to take into consideration dietary, social and demographic patterns associated with time to determine what is acceptable for physiological wear.47 This makes the diagnosis between physiological and pathological a little more difficult to determine as it is ever changing.

Abfraction

Abfraction has caused much debate as to whether it is an accepted form of tooth wear. Much research has developed from finite element studies with little clinical evidence.48, 49, 50 As TW is often multifactorial in nature, it is debated that abfraction is a manifestation of a combination of erosion, abrasion and attrition.46 Erosive processes may lead to subsurface mineral loss, which leads to a softening of the tooth surface. Abrasion and attrition may lead to an acceleration of the tooth wear processes in the cervical region.

Clinical presentation

Due to the multifactorial aetiology tooth wear can present in a variety of clinical appearances, making a diagnosis may be difficult. Occasionally, one causative factor may be dominant and indicative of the main cause, but often the clinical appearance is the result of cumulative damage over a period of time. Tooth wear may present as localized or generalized loss off tooth substance, depending on the number of teeth affected.

Patients may be unaware of the presence of tooth wear, especially in the early stages of the process. However, often patients present complaining of reduced aesthetics. Occasionally, patients complain of the appearance of reduced lower facial height, however, due to alveolar compensation, this is not often a presenting feature. Dentists may note a reduced interocclusal space for restorations. Enamel may fracture and the teeth appear shorter.23 Loss or thinning of the enamel may lead to shine through or exposure of the underlying dentine, changing the optical properties and colour of the teeth.45 Patients may complain of symptoms of dentine sensitivity and impaired function.51 Other reported symptoms of burning mouth syndrome, oral ulceration and parotid gland enlargement may be provided.52

Attrition

Attrition, as previously defined, results in loss of the cusp tips or incisal edges which generally interdigitate with the occluding dentition. 53 Initial presentation may involve localized occlusal cusp tips and the palatal surfaces of the maxillary anterior teeth showing loss of tooth structure. As the process progresses, dentine may become exposed, leading to flattening of incisal edges and cusp tips. The matching opposing surfaces wear at the same rate and so the teeth continue to interdigitate (Figure 1).

Erosion

Often, early erosive lesions are not noticed by the patient. The cause of the erosion can determine, to some extent, the clinical presentation as the location and severity may differ.5 If the erosive process is currently active, there is often no staining of the teeth. If dentine is exposed and stained, often the erosive element is no longer occurring.

In general, erosive lesions present clinically when in enamel only as rounded and smooth lesions with loss of surface contour. Once the enamel layer has been lost, exposed dentine is more susceptible to the acidic attack and the accumulation of tooth wear factors, leading to a more rapid loss of tooth substance. This can lead to cupping or dished out lesions. Teeth may appear translucent, due to thinning of the enamel anteriorly, or darker due to the exposed dentine. Anterior teeth may chip or fracture and restorations may stand proud from the teeth. A chamfer margin of enamel is often observed.54

In extrinsic erosion, for example from dietary intake, tooth wear is often observed on the buccal cervical surfaces of the maxillary teeth and the occlusal surfaces of the mandibular posterior dentition.13 It has been suggested that erosive and abrasive TW can be differentiated, in the cervical region, as erosive wear tends to create broader dished-out shallow lesions in comparison to the sharply defined margins associated with abrasion.55

In intrinsic erosion, TW tends to present on the palatal surfaces of the maxillary dentition. The lingual surfaces and lower anterior teeth are often not affected due to the protective nature of the tongue covering them from exposure to the acid attack41 (Figure 2).

Abrasion

Clinical presentation is dependent on the causative factor and will affect the severity and distribution of the wear. Localized lesions may be the result of a habit such as pen-chewing, nail-biting, pipe-smoking, or present as an occupational issue, such as builders holding screws between their teeth. The tooth wear pattern will fit the shape of the object causing the wear.

Overenthusiastic toothbrushing often presents as rounded grooves in the cervical region of teeth; again this can present as a localized problem, often with the canines and premolars being most affected, or as a more generalized condition dependent on the patient's toothbrushing technique. Of note, right-handed individuals tend to create more wear on the left side and vice versa (Figure 3).

Abfraction

Abfraction lesions can present similarly to toothbrushing abrasion cavities, but tend to be more angular and undercut at the coronal aspect where enamel overhangs the defect.

Examination of the tooth wear patient

For patients presenting with tooth wear, the extra-oral examination should include an assessment of their temporomandibular joints and associated musculature. The presence of any clicking, crepitation, mandibular deviation on opening or closure, maximum jaw opening (less than 40 mm is considered restricted) and any associated muscle tenderness/aches/pain should be recorded.56 It is also worth noting the presence of parotid gland enlargement, which is often seen in bulimic patients.

Severe tooth wear patients may present with a reduced lower facial height due to over closure from loss of vertical tooth height. Due to this, the facial vertical proportions should be noted. This can be examined by assessing the freeway space (FWS), by determining the patient's resting vertical dimension (RVD) and occlusal vertical dimension (OVD). Callipers or a Willis gauge can be used for this. Other simple techniques include the use of phonetic assessments (particularly the sibilant sounds) and facial soft tissue contour analysis.57 The patient's smile aesthetics may also be examined looking at the smile line and lip line.

A full intra-oral examination should be undertaken including a detailed soft and hard tissue assessment. The level of oral hygiene should be recorded together with the undertaking of a Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE). An occlusal assessment may be required for moderate to severe wear.

Measuring and monitoring tooth wear

A large number of indices have been developed over the years, including the more popular Tooth Wear Index (TWI)13 and the Basic Erosive Wear Examination (BEWE).58 However, at present, a single universally accepted method of quantifying and recording tooth wear is yet to be adopted.59 This can make recording and documenting TW difficult.

Some indices record wear based on the aetiology; however, the majority of indices that have been developed are based on the diagnosis and monitoring of the wear. These indices tend to distinguish severity of the wear and are often numerical in nature. Measuring wear in vivo is difficult for a clinician as indices can only provide the prevalence of wear at the point of time of recording as there is a lack of reliable natural reference points for continuity. The majority of indices rely subjectively on visual assessment of the wear severity, which can lead to a conflict of opinions from different clinicians. Furthermore, the vast number of indices available makes comparison and aggregation of data challenging.6

The Tooth Wear Index, developed by Smith and Knight,13 is the most widely utilized. It was designed to be of use in research into the aetiology, prevention, management and monitoring of tooth wear and epidemiology. It was the first index of its kind to measure and monitor multifactorial tooth wear. It is a comprehensive index whereby the four surfaces of a tooth are scored according to clinical findings based on the level of enamel lost, level of dentine lost and change of the contour of the surface. Smith and Knight13 proposed a distinction of pathological levels of wear based on a patient's age.

However, there are several limitations to this index.11 The thresholds for each age group have been criticized with subsequent underestimation of pathological wear.59 A number of suggestions have been proposed to improve the TWI, including modifying the threshold values for pathological wear, expanding the scoring criteria and creating another scoring level for secondary dentine and pulpal exposure. Millward et al60 modified the TWI to study erosion in primary and secondary dentine by grouping TWI scores into categories of ‘Mild’, ‘Moderate’ and ‘Severe’. Again, there is potential for overestimation of tooth wear. Fares et al61 undertook the most recent modification of the TWI to produce the Exact Tooth Wear Index. This index scores wear for enamel and dentine separately. It has the potential for scores to be converted into the original TWI for research purposes for comparison and review.

The above indices tend to be quite comprehensive and often used for research. Bartlett et al58 designed The Basic Erosive Wear Examination (BEWE). It is a simple index, based on the principles of the Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE) as a screening tool for tooth wear. The BEWE is a partial scoring system recording the most severely affected surface for each sextant. This can then be utilized to guide management of the condition, much like the BPE for periodontal disease. This index has been found to be easy to use by general dental practitioners and researchers alike. Studies have found the BEWE to be an acceptable method for scoring erosion with good inter-examiner reliability when scoring sound surfaces and TW into dentine, but more discrepancies were recorded when scoring enamel lesions.62

A new classification, proposed by Vailati and Belser,63 the Anterior Clinical Erosive classification (ACE), aims to provide a tool that is easier to use than the BEWE for clinicians. Patients are grouped into six classes based on five parameters relevant to the treatment and the prognosis:

A dental treatment plan is suggested for each class.63 Much like the aforementioned BEWE and the well-known Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE) utilized for assessing periodontal disease, the most severely affected tooth is used to decide the classification. It is worth noting that the classification is specifically for the anterior maxillary dentition, however, assessment and treatment of the posterior dentition must also be planned as an integral part of the definitive oral rehabilitation, which is a limitation of this classification.

The difficulty with all the indices is that they are subjective and potentially insensitive to small changes. Some, such as the TWI, may be time consuming in a general dental practice setting when compared with the BEWE and ACE. However, both are good for assessing the level of tooth wear and how best to manage the condition. Alternative methods to measure TW include using intra-oral three-dimensional laser scanners; sequential photographs; periodic accurate study casts; sectional silicone index and radiographs, which have all been utilized in clinical settings with varying results. Furthermore, assessing the patient clinically and for changes in reported symptoms, ie the patient begins to notice increased tooth wear or sensitivity, should also be utilized for measuring TW.

Diagnosis

The difficulty in distinguishing between the clinical presentations and often multifactorial nature of tooth wear can make diagnosis difficult. It is important to take into consideration whether the wear is physiological or pathological. A detailed history of the chief complaint should be ascertained and documented. Alongside this, also record an accurate and up-to-date medical history assessment of the clinical signs and symptoms and the location of the wear (generalized or localized) when creating a diagnosis.

The diagnosis of a patient presenting with tooth wear should include a description of the type(s) of lesions observed, together with an account of the extent/location (localized, anterior/posterior or generalized) and severity (restricted to enamel only, into dentine or severely affecting the teeth involving the pulp) of the condition.

Prevention

The increase in incidence of tooth wear, especially in children, is concerning as, without appropriate prevention, this is likely to continue into adulthood.64 The correct diagnosis is essential for successful prevention and management. Even though prevention is of utmost importance, there is little high quality evidence about the clinical effectiveness of most preventive measures.65 Furthermore, it is difficult to predict which individuals will be affected by TW, making primary prevention difficult to achieve.

The decision to treat arises when the extent of the tooth wear and potential for progression may affect the prognosis of the tooth, or the patient expresses a want for treatment, or there is the presence of symptoms. In the absence of functional and aesthetic issues, monitoring and counselling may be the preferred treatment option.66

It is reported that, once TW has been diagnosed, wear progression appears to occur at a relatively slow rate whilst the enamel is still present, particularly in cases where preventive advice has been successfully implemented.66, 67 However, a change in lifestyle and personal circumstances, including an increase in stress, may be associated with sporadic bursts of wear activity amongst these patients, which may have the potential to produce severe wear. Therefore, early preventive advice is paramount to success in preventing ongoing wear leading to possible highly restored dentitions with long-term management requirements. Most research into the efficacy of preventive strategies has focused on the prevention of erosive wear. Preventive advice should be structured in relation to cause.

Preventive advice may be centred on medical management with referral to a medical practitioner or psychiatrist.68 This is considered appropriate when an eating disorder or reflux disease is suspected. Medication, such as antacids, omeprazole and ranitidine can be used to reduce gastric reflux and acid production. Where xerostomia may have an underlying role, referral to a specialist in oral medicine may be considered; or discussing with the medical practitioner an alternative medication if xerostomia is a side-effect of a current medication regimen. For example, in cases of acid erosion, avoidance of further exposure of the tooth to acid is paramount.66 A reduction in the quantity and frequency of the consumption of acidic food/drinks would be beneficial. Patients should also be advised to limit their consumption of acidic foods/drinks to meal times. A change of habit, so that when acidic drinks are consumed they are drunk through a wide bore straw, plus avoidance of swishing beverages in the mouth, will help to reduce the rate of dental erosion. It has been found that consuming dairy products, including hard cheese or chewing gum after the ingestion of an acidic substances, is beneficial in promoting the re-hardening of enamel, stimulating saliva flow and increasing the saliva pH and reducing the effects of the erosive source.69

Appropriate toothbrushing advice and habit avoidance or counselling will also be of benefit to the patient, including the avoidance of overzealous toothbrushing and the use of less abrasive toothpastes such as those marketed for tooth whitening. Toothbrushing shortly after acid exposure (commonly practised after vomiting or after drinking citrus juice in the morning) should be avoided. Studies have shown that remineralizing toothpastes increase the surface hardness of teeth exposed to acidic substances and have a greater effect than conventional fluoride-containing toothpastes alone.70 However, topical fluoride application has been shown to protect against subsequent tooth wear following an acid challenge. A neutral sodium fluoride mouthrinse or gel should be recommended.

Furthermore, fluoride application can also aid in prevention of symptoms of sensitivity. Toothpastes containing potassium and Tooth Mousse ACP (GC) are also considered to be appropriate for the management of dentine sensitivity.56 Such agents may be applied with the aid of a custom-fabricated tray (containing reservoirs akin to bleaching trays). For patients experiencing sensitivity this may be prevented by the application of dentine-bonding agents, and fissure sealant to erosive lesions may be of some benefit. However, studies have shown the longevity of dentine-bonding agents applied to teeth displaying severe wear to be relatively short lived.71 Glass ionomer cements can also be readily applied to worn surfaces for the purposes of sensitivity and tooth wear prevention.

Advising patients to change habits, such as that of pen/pencil-biting, nail-biting or holding or opening objects with the teeth, such as bottle tops, hair grips, sewing needles, pipes, will also help prevent ongoing wear.

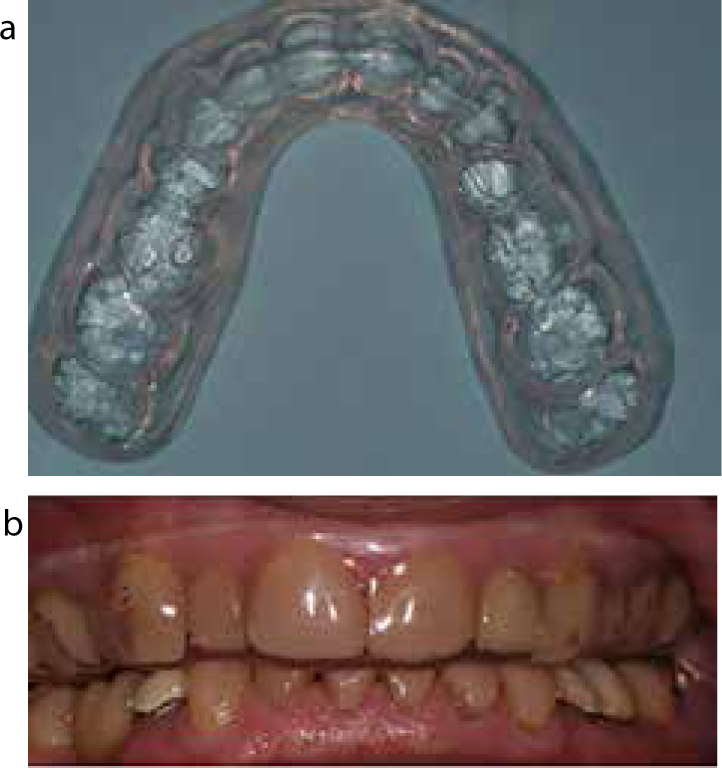

In cases of tooth wear, splint therapy is beneficial in order to prevent the loss of tooth structure from attrition. The use of a night guard is recommended for nocturnal bruxists. This may be a soft splint, but this will not be durable in the long term. A bilaminar splint may be more cost-effective72 (Figure 4). However, for an established bruxist patient, a full coverage hard acrylic occlusal splint should be constructed (ie a Michigan splint or a Tanner appliance). The splint should be fabricated to provide an ‘ideal occlusion’ (Figure 5). It is important to take precautions when providing splints to patients with an erosive factor, in the cause of the tooth wear, especially if night reflux is a causative factor. Advice should be given to the patient accordingly, as the acidic substances may accumulate within the splint and further exacerbate the rate of wear, and regular maintenance is required. Splints may be used to protect teeth during episodes of vomiting for the bulimic patient, which are worn during the vomiting period only and after vomiting should be removed and cleaned. Again precautions and instructions on wear/usage must be precise, so that the splint does not become a reservoir for the acid produced. In erosive tooth wear a soft vacuum-formed appliance modified to include reservoirs is beneficial. Neutral fluoride gels, desensitizing agents and also acid neutralizers, ie sodium bicarbonate solution, can be applied, respectively.56

Key points

Parts 2 and 3 of these guidelines will be published in the next two issues of Dental Update.