References

A case of five mandibular incisors

From Volume 44, Issue 8, September 2017 | Pages 787-792

Article

Supernumerary teeth may be single or multiple, unilateral or bilateral, and may occur in one or both jaws. The incidence of supernumerary is 1–3% and most occur in the maxillary anterior region, followed by maxillary molars, and the (maxillary/mandibular) premolars.1

Multiple supernumerary teeth are often found in syndromes such as cleidocranial dyostosis, Gardner's syndrome and cleft lip and palate. However, the occurrence of a supernumerary tooth is rare in the incisor region of the mandible. The first case of bilateral supernumerary mandibular incisors was reported by Tanaka et al in Japan.2 Bodin et al examined 21,609 patients and found 422 supernumerary teeth, of which only four were seen in the mandibular incisor region.3 Locht studied the radiographs of 704 children and found no cases of supernumerary teeth in the anterior part of the mandible.4

The incidence in the mandibular anterior tooth area is about 0.01% and there have been few cases of five mandibular incisors reported in the literature.1,5,6,7 Clinicians are often faced with the dilemma of distinguishing a supplemental incisor from its parent tooth. This case report will help in the diagnosis and indicate where there is a need for extraction of the supernumerary.

Case report

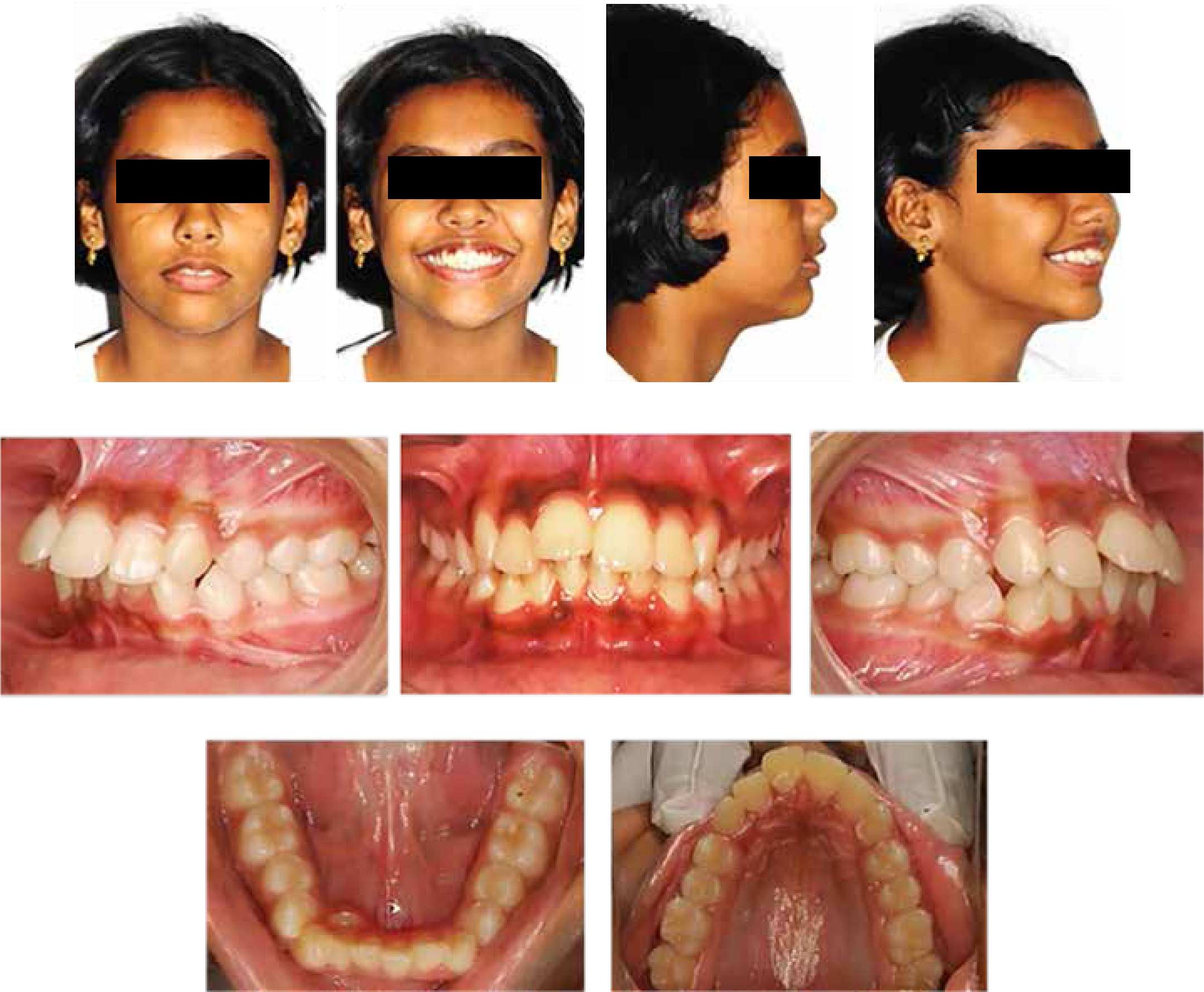

A 14-year-old female patient complained of anteriorly placed front teeth. On clinical examination, she had a mesoprosopic facial form, a convex profile with incompetent lips and an incisal show of 4 mm at rest. Intra-oral examination revealed a Class II malocclusion with an overjet of 5mm and lower anterior crowding of 4mm. An additional (lingually erupting) mandibular incisor was noted. An intra-oral periapical radiograph (IOPA) revealed normal mandibular incisor root morphology.

Diagnostic records included extra-oral and intra-oral views (Figure 1), a lateral cephalogram and an orthopantomogram (OPG) (Figure 2). Pre-treatment cephalometric analysis revealed a Class II skeletal base (Wits Appraisal = +5 mm) with average inclination of mandibular incisors (IMPA = 94°, Lw1–NB = 24° and 6 mm), proclined maxillary incisors (Up1–NA = 46° and 12 mm) and a normo-divergent facial pattern (SN–MP = 28°) (Figure 2).

Distinguishing a supplemental tooth from a supernumerary mandibular incisor was important and the decision to retain or extract depends on many factors, discussed below.

Treatment objectives

The treatment objectives were correction of:

The treatment plan was extraction of first premolars and ectopic mandibular incisor to:

Treatment progress

Fixed orthodontic appliances (Mini Series, American Orthodontics, Sheboygan, WI, USA) (0.022”x0.028” Roth prescription) was started in April 2012. Levelling and aligning was complete in 3 months with wires in the following sequence: 0.016”NiTi (Nickel Titanium), 0.016”x0.022”NiTi, 0.017”x0.025”NiTi. Class II elastics were used to facilitate correction of Class II canine relation. Anterior retraction was done on 019”x025” SS using elastomeric chains, finishing and settling of occlusion using 3/16” elastics for 3 weeks. Total treatment time lasted 16 months. A two-year post-treatment follow-up showed that the occlusion was stable with no sign of relapse (Figure 3).

Treatment result

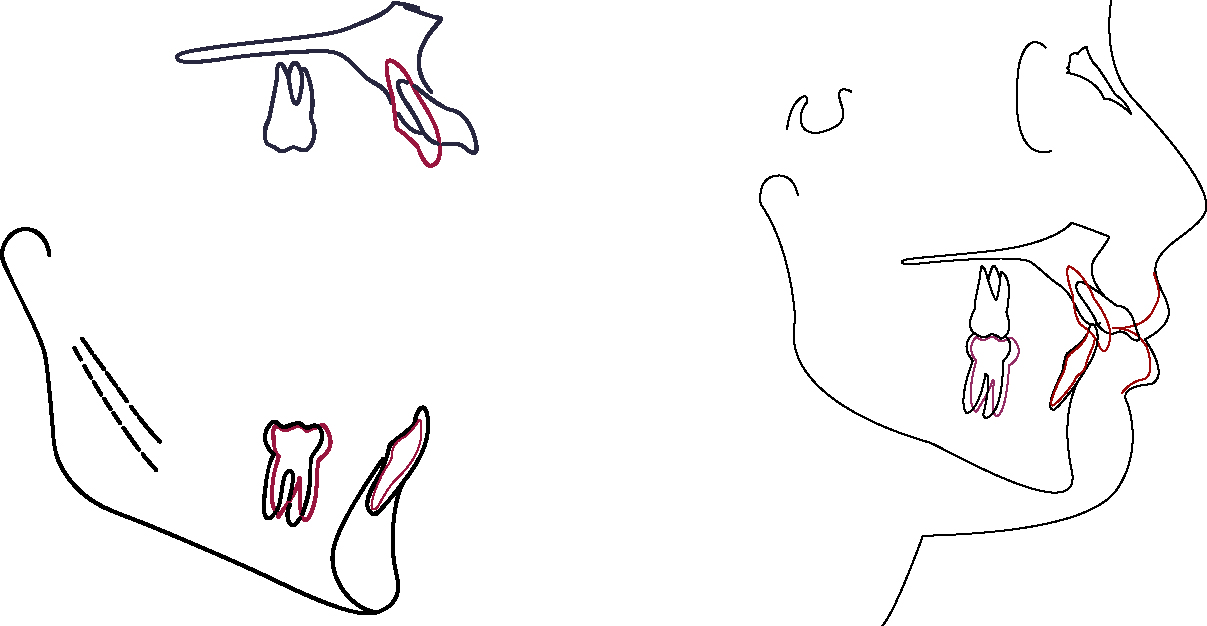

Post-treatment lateral cephalometric analysis revealed a Class I skeletal base (Wits Appraisal = +2 mm) with average inclination of lower anteriors (IMPA = 95°, Up1–NA = 24°, Lw1–NB = 26°) and a normo-divergent facial pattern (SN–MP = 26°) (Figure 4).

Maxillary and mandibular superimpositions showed maxillary incisor retraction of 5 mm and mandibular incisor retraction of 4 mm. Soft tissue superimpositions indicated an improvement in the profile with upper lip retraction of 3 mm and lower lip retraction of 3 mm (Figure 5) (black line indicates pre-treatment tracing and red line indicates post–treatment tracing).

Discussion

Supernumerary teeth are either eumorphic (same morphology as a normal tooth) or dysmorphic (conical or tuberculate).8,9 Some authors have debated similarities (topographic distribution, pathologic manifestations, genetic and immuno-histochemical factors) between odontomes and a supernumerary. Although odontomas and supernumeraries are classified as distinct entities, they seem to be the expression of the same pathologic process, either malformative or hamartomatous.10 Our patient presented with a eumorphic mandibular incisor.

Various authors have suggested local hyperactivity of dental lamina,11 splitting of tooth germs resulting in more than one tooth at any moment of odontogenesis, dichotomy theory,2,11,12 supplementary evagination resulting from local irritation or purely accidental cellular induction,2,11 atavism (reversion to ancestral human dentition), hereditary and environmental factors 8,9,11,12 as possible theories.

The dichotomy theory stated that a complete equal split of the tooth bud would result in two supplemental forms, whereas an unequal split would result in one normal tooth and one supernumerary tooth. The dental lamina theory believed that the supplemental form comes from the lingual extension of an accessory tooth bud, whereas the rudimentary form is derived from the proliferation of an epithelial remnant of the dental lamina.

Consequences of an additional mandibular incisor are, delayed or ectopic eruption of adjacent teeth, crowding, cystic formation, impaction and root resorption of adjacent teeth. Our patient presented with lower anterior crowding.

Supernumerary teeth in the mandibular incisor region may be seen in some autosomal dominant hereditary syndromes, like Gardner's syndrome (characterized by supernumerary teeth, compound odontomas, hypodontia, abnormal tooth morphology and impacted or unerupted teeth) and Weyer's acrofacial dysostosis (characterized by oligodontia, enamel hypoplasia, and conical teeth).13,14 However, Cassia et al had described this trait as an autosomal recessive in a large Lebanese family (where four individuals displayed five incisors in the anterior mandible).15 The hereditary role of this trait was ruled out in our patient based on the clinical presentation.

Two features that distinguish a normal mandibular incisor tooth from its supplemental tooth are a deep cingulum pit and a coronal invagination.

However, in addition, the mandibular lateral incisor is approximately 1mm wider than the mandibular central incisor. The incisal edge of the latter is at right angles to a line bisecting the crown labio-lingually but, in the former, it follows the curvature of the mandibular dental arch, giving the crown the appearance of being twisted slightly on its root base. The mesial side of the crown of the mandibular lateral incisor is often longer than the distal side, causing the incisal ridge to slope downwards in a distal direction. 16

According to Jose-Antonio Canut, the extraction of a mandibular incisor is indicated when there are the following features:

The extraction of an incisor is contra-indicated when:

Hence a decision to extract the eumorphic mandibular incisor (in addition to premolars) was made to maintain coincident dental midlines and a Class I canine relation.

Conclusion

Several factors (such as mild-to-moderate Class III malocclusion, an edge-to-edge anterior occlusion or anterior crossbite, with mild anterior mandibular tooth size excess and minimal open bite tendencies) could lead to good outcomes of orthodontic treatment following mandibular incisor extraction. However, clinicians should be careful to avoid poor outcomes, such as gingival recession, open interproximal gingival embrasures, increased overjet and overbite.