Abstract

Acute trigeminal pain is a common presentation in the dental surgery, with a reported 22% of the US adult population experiencing orofacial pain more than once during a 6-month period.

From Volume 42, Issue 5, June 2015 | Pages 442-462

Acute trigeminal pain is a common presentation in the dental surgery, with a reported 22% of the US adult population experiencing orofacial pain more than once during a 6-month period.

‘A toothache, or a violent passion, is not necessarily diminished by our knowledge of its causes, its character, its importance or insignificance’ wrote T S Eliot.

Acute pain management is integral to the provision of optimal dental care and supporting the well-being of patients. Any patient attending a dentist will be experiencing some degree of anxiety and stress. These emotions will lower the patient's pain tolerance and further compound pain management. Anyone in this field recognizes that pain is complex, particularly in the dental environment where fear, phobia and poor expectations compound the patient's pain experience. Dentists require an armamentarium of psychological, communication, medical and technical skills. Managing operative pain under local anaesthesia requires expertise, empathy and patience. Oral analgesics are commonly prescribed for a few days following oral surgery or other procedures, after which patients are typically pain-free or can switch to over-the-counter (OTC) medications (ie either lower doses of the same analgesics or different OTC drugs).

Acute trigeminal pain is a distressing, common encompassing pain from the orofacial region and head.2 A cross-sectional population study in Cheshire, England, reported that orofacial pain (OFP) affected a quarter of the population, of whom only a half sought help.3 The prevalence was higher in women and younger adults (18–25 years) with 17% of the population having time off work or unable to carry out normal activities due to the pain.3 The impact of pain on the economy is demonstrated by a cross-sectional survey in eight countries in Europe which estimated the total annual cost of headache among adults, aged 18 to 65 years, as €173 billion.4

The dental profession, since its infancy, has been a pioneer in the fields of anaesthesia and pain control. This stems from the need for these modalities to render painless dental care in an anatomic region that is highly innervated by the second and third divisions of the trigeminal nerve. Pain has a dramatic physiologic impact that can adversely affect the health and well-being of dental patients.5 Furthermore, if acute pain is not treated adequately, there is a risk that it may become chronic in nature. Therefore, adequate pain control is a medical and dental necessity and not merely an issue of patient comfort.

It is now understood that early control of acute pain can shape its subsequent progression, by preventing nociceptive input and, hence, preventing persistent pain.6 Good pain management can help prevent the negative physiological (tachycardia, hypertension, myocardial ischaemia, decrease in alveolar ventilation, and poor wound healing) and psychological (anxiety, sleeplessness, phobia) outcomes.5

Management of acute dental pain includes management of patients undergoing surgery (peri- and post-operative) and those presenting with pain as a result of underlying pathology (eg pulpitis, ulcer). Patients with trigeminal pain may often present to dental practitioners. Successful management of acute trigeminal pain is dependent on obtaining a correct diagnosis of the source of pain.7 This is achieved through comprehensive history-taking, examination and appropriate special tests (Table 1). Initial history-taking should include determining the site, onset, character (type of pain), severity (verbal/numerical, Table 2) and any exacerbating/relieving factors. A thorough assessment can be completed taking into account associated signs and symptoms, radiation, functionality, disability, psychological effects and time course. Management of acute pain7 as a presentation symptom is discussed in later articles.

| Diagnostic Requirements | |

|---|---|

| Identify signs of inflammation | Redness, swelling, heat pain, loss of function |

| Loss of function | Trismus, inability to bite on tooth, difficulty swallowing |

| Special tests (Endofrost/Electric pulp test/heat) | NB Surrogate measure of vitality as it measures nerve response rather than condition of blood supply |

| Neuropathic signs | Mechanical allodynia (pain to stimulus which is not normally painful eg light touch) |

| Radiographs | Long Cone periapical using paralleling technique for individual to three teeth in single quadrant |

| Haematological investigations | CRP levels in acute spreading infections |

| Biopsy | Punch, classical, laser biopsy for lesions of unknown aetiology for histopathological diagnosis |

| Signs of sinister disease | Over 50 years |

| Pain assessment tool | Assessment |

|---|---|

| Category rating scale | Choice of five categories: None, Mild, Moderate, Severe, Unbearable |

| Visual analogue scale (VAS) | Draw a line from no pain to worst pain |

| Numerical rating scale | Choose a number from 1–10 |

The management of acute trigeminal pain can be divided into three areas: intra-operative, post-operative and acute symptomatic pain (usually acute infection).

The mechanism, peripheral mediators, central modulation and the trigeminal anatomy of pain have been covered in Part 1 of this series.

The clinician is beholden to take a full and comprehensive history to build trust and understanding of the patient and his/her complaint. Acute pain will have onset in the last days/weeks and generally has been present for less than 3 months. The pain may be associated with key inflammatory signs (tumor, dolor, calor, rubor and loss of function) but if caused by a ‘cold bacteria’ may not have the traditional inflammatory signs (eg dry socket). Acute pain is inflammatory pain responding to anti-inflammatories (eg paracetamol and NSAIDs) and antibiotics, if related to an infective cause.

There is no absolute measure of pain as it is a purely subjective experience. However, pain assessment is essential in diagnosing and monitoring a patient's response to treatment. Pain rating scales are often used in assessing pain intensity. They are quick and easy to use (Table 2),8 whereas pain questionnaires can often assess the quality and character of the pain (eg McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ)), as well as its intensity.9 The MPQ consists primarily of three major classes of word descriptors; sensory, affective and evaluative to specify the pain experience.8

Local anaesthesia (LA) is fundamental for pain control in outpatient oral surgery and dental procedures. Local anaesthetic is defined as a drug which reversibly prevents transmission of the nerve impulse in the region to which it is applied, without affecting consciousness.10 It is frequently used to control intra-operative and immediate post-operative pain. During acute tissue trauma mediated pain (eg tooth extraction), local anaesthetic blocks the pain signal transmission to the cerebral cortex, preventing pain perception and processing. Hence, local anaesthetic should always be used, even if the patient is under general anaesthesia, as it prevents nervous system sensitization and, hence, reduces post-operative pain.11

Local anaesthetic agents bind to sodium channels on axons, thus inhibiting the rapid passage of sodium ions and propagation of an action potential. There are two theories of the mechanisms of action of local anaesthetic both of which involve perturbation of the nerve cell's sodium channels and, hence, prevention of nerve depolarization and firing. The membrane expansion theory suggests non-specific swelling of the cell membrane by absorption of the LA, whilst the newer specific binding theory describes binding of LA to a specific binding site of the sodium channel. Discovery of specific drug binding sites allows for the possibility of developing anaesthetics with greater sensitivity for specific sodium channels with reduced side-effects.12

Lidocaine is the most commonly administered local anaesthetic by dental practitioners, although other available solutions (prilocaine, mepivacaine and articaine) offer advantages in certain situations (Table 3). In the severely medically-compromised patient, such as those with unstable angina, an adrenaline-free solution such as 3% prilocaine with felypressin should be used.13 In a meta-analysis, articaine 4% was found to be superior to lidocaine 2% in anaesthetizing lower first molars.14

| LA solution | Vasoconstrictor | Duration | Use | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lidocaine (2%) | 1:80,000 epinephrine | Intermediate | General dentistry, minor oral surgery | Inferior alveolar nerve block (IDB) necessary to anaesthetize lower molar |

| Prilocaine (3%) | Felypressin | Intermediate | General dentistry, minor oral surgery |

|

| Mepivacaine (2%) | 1:100,000 epinephrine | Intermediate | General dentistry, minor oral surgery | |

| Articaine (4%) | 1:100,000 epinephrine | Intermediate | Effective infiltrations to anaesthetize ‘Hot’ pulps and lower molars | Unfounded claims of increased risk to nerves (IDN, lingual) during IDB |

| Bupivacaine (0.5%) | 1:200,000 epinephrine | Long-acting | Oral surgery of long duration/invasive procedures, eg osteotomies | Increased toxicity compared to other anaesthetics CNS and cardiovascular adverse effects |

| Levobupivacaine (0.5%) | 1:200,000 epinephrine | Long-acting | Oral surgery of long duration/invasive procedures, eg osteotomies | Reduced toxicity compared to bupivacaine |

Although there are limited scientific studies in which local anaesthetics with higher concentrations (4%) result in higher incidence of paraesthesia,15 there remains a trend to avoid articaine 4% use in inferior alveolar nerve (IAN) blocks. Local anaesthetic related lingual nerve injury is most likely to occur when multiple inferior alveolar nerve blocks are given, regardless of the local anaesthetic agent used.16 Importantly, buccal infiltration articaine will most likely avoid inferior dental blocks with lidocaine for most of dentistry, also reducing the likelihood of IAN LA-related injuries.

Studies have suggested benefit in using bupivacaine (Marcaine), a long-acting local anaesthetic, to limit post-operative pain following third molar surgery17,18 and endodontic treatment.19 Reports range from a reduction in pain at 8 hours18 to 7 days17 post-operatively. It is important to note that bupivacaine exhibits this property only when used as a nerve block and not when used as an infiltration. Levobupivacaine is a newer anaesthetic solution with an improved safety profile than, and equivalent efficacy to, bupivacaine (the latter has rare reports of causing severe central nervous system (CNS) and cardiovascular adverse effects).20 A double blind study showed similar anaesthetic efficacy between bupivacaine (0.5%) and levobupivacaine (0.5%) in inferior alveolar nerve blocks, suggesting that levobupivacaine is a useful alternative to bupivacaine owing to its lower toxicity.21

Cognitive and psychological factors are reported to play a significant role in the severity of reported postsurgical pain.22 If patient anxiety prevents the ability to comply with dental procedures under local anaesthesia, then anxiolysis can be provided using oral, inhalational or IV sedation techniques.23 General anaesthesia should be considered if local anaesthesia is contra-indicated.

Failure of inferior alveolar nerve blocks to anaesthetize teeth with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis (‘hot pulps’) is partly due to inflammatory prostaglandin production inducing peripheral nociceptor sensitization and central sensitization.24 Studies have demonstrated that the use of ibuprofen and paracetamol before the inferior alveolar nerve block does not statistically improve success rate.24,25 This is likely to be due to the fact that sensitization has already taken place, and NSAIDs cannot reduce the amount of prostaglandin already present but rather may limit further production.

Preventive/pre-emptive analgesia is a treatment that is initiated before the surgical procedure to prevent nociception and, hence, sensitization of the peripheral and central pathways.26,27 Although there are many studies in general surgery which report the benefits of pre-emptive analgesia in reducing the post-operative pain experience, there are limited studies in relation to dental surgery (see section on NSAIDs), with some studies reporting no benefit.28 Dahl et al highlight the need for improved design of clinical studies in order to achieve more conclusive answers regarding the different preventive interventions.26,27

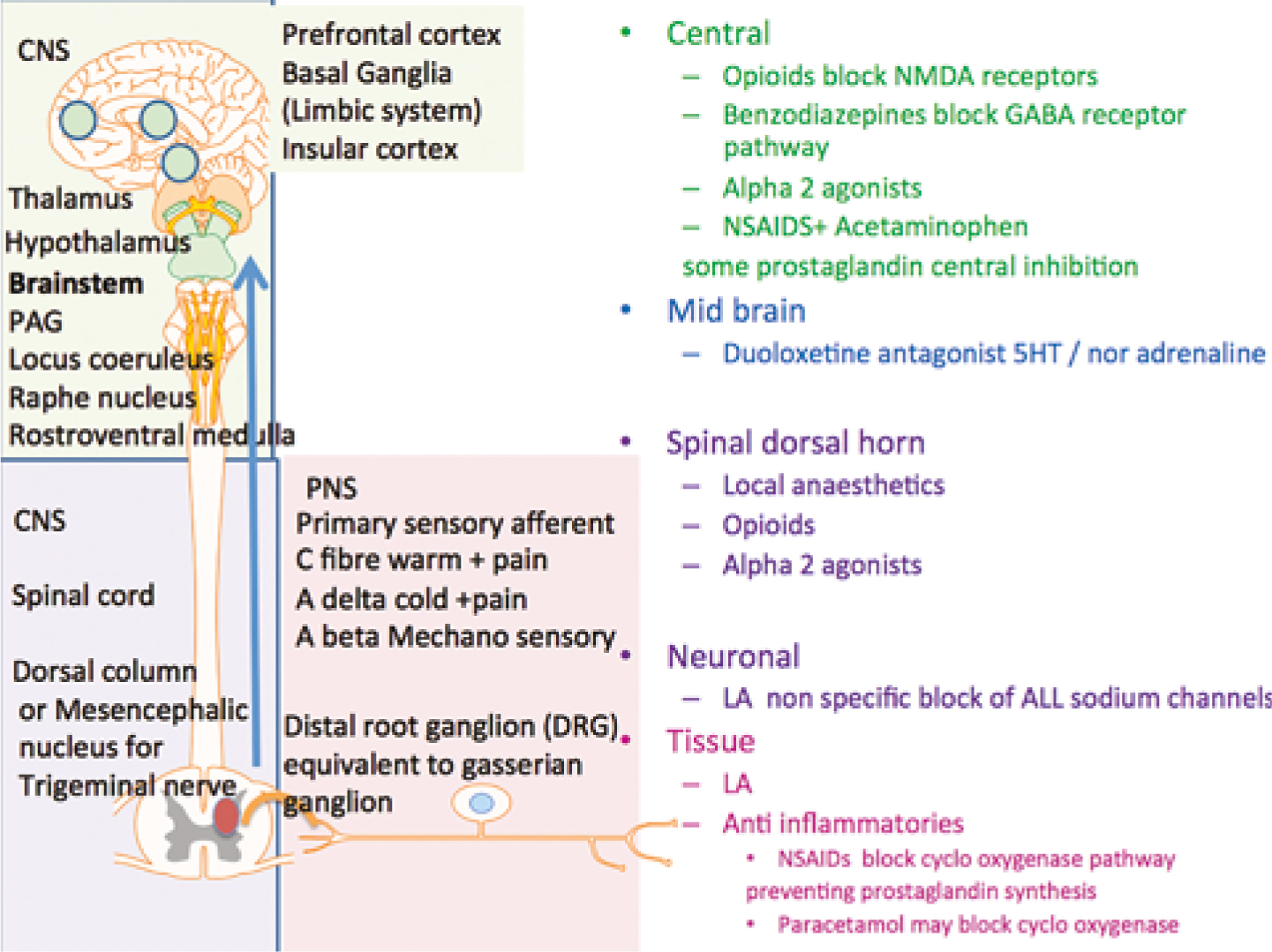

Effective post-operative pain management is fundamental to quality dental care, and is likely to speed recovery. Conventional analgesics act by interrupting ascending nociceptive information or depressing interpretation of the information within the CNS. For dental or routine day case surgery post-surgical pain control, oral analgesia prescribed are usually over-the-counter (OTC) analgesic medications including, NSAIDs, paracetamol, opiates or combinations of these medications. Their pharmaco-mechanisms for pain reduction remain not fully understood but what little is known is illustrated in Figure 1.

Analgesics are classified as opioids or non-opioids and may act at different sites, depending on their mechanism of action. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) decrease pain resulting from inflammatory reactions (arachidonic acid cascade). Opioids may affect emotional aspects of pain and can modify transmission of pain information in the dorsal horn (descending modulation). Non-opioid analgesics (including paracetamol and NSAIDs) have been demonstrated to be superior analgesics in dental pain compared to opioids at conventional doses.27

A meta-analysis of Cochrane reviews of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) testing the analgesic efficacy of individual oral analgesics in acute post-operative pain has helped facilitate indirect comparisons between oral analgesics.29 The results from this review and previous systematic reviews of randomized post-surgical analgesic trials helped to formulate the Oxford League Table of Analgesics in Acute Pain,30 which is used by healthcare professions worldwide. Analgesic efficacy is expressed as the number-needed-to-treat (NNT). This estimates the number of patients who need to receive the analgesic for one to achieve at least 50% relief of pain compared with a placebo over a six-hour treatment period. The more effective the analgesic, the lower the NNT. The Bandolier NNT table shows that oral NSAIDs perform well, and that paracetamol in combination with an opioid is also effective.

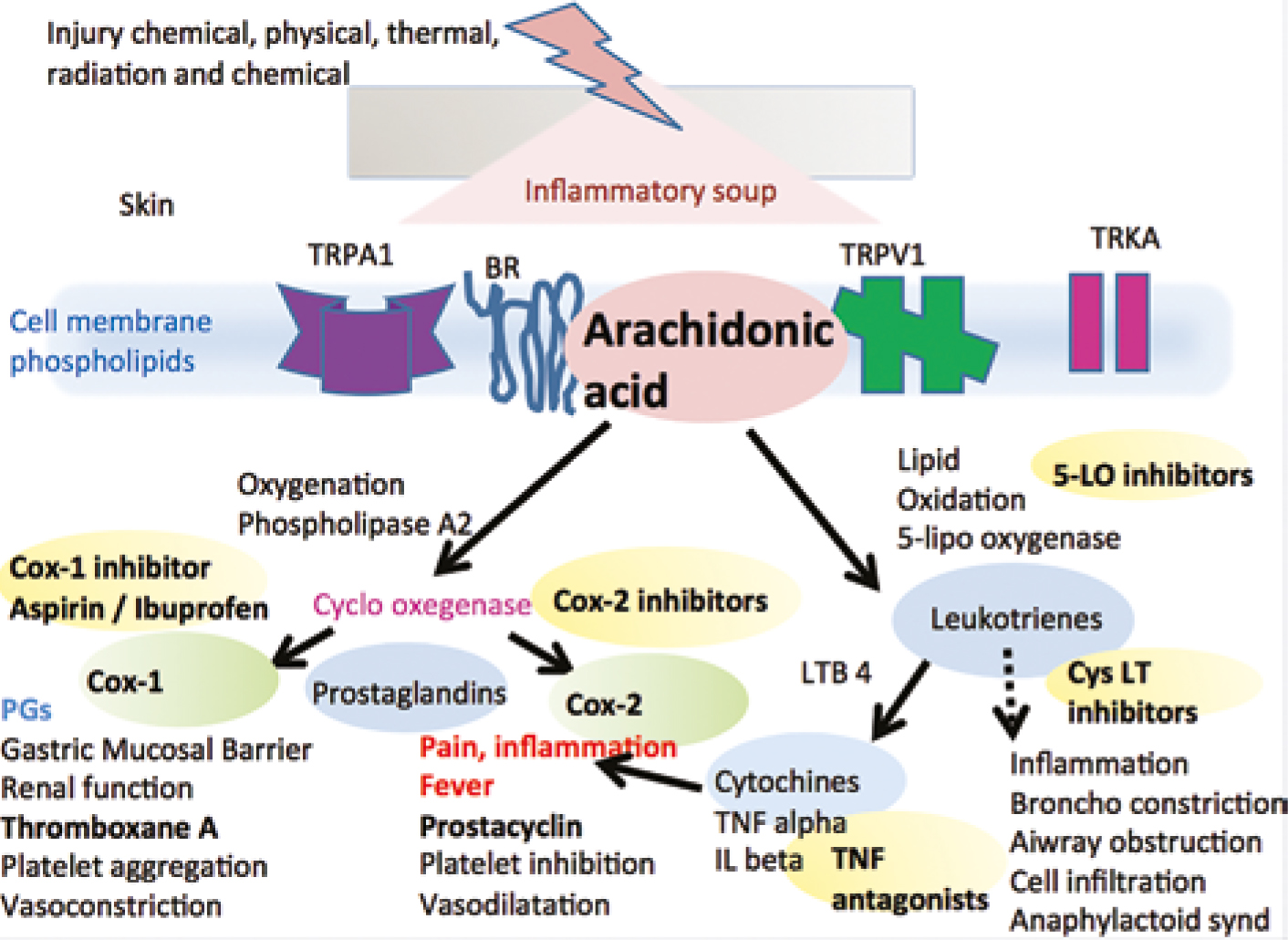

NSAIDs are known for their analgesic, antipyretic and anti-inflammatory properties. These therapeutic effects, as well their associated side-effects, are mostly due to NSAID inhibition of the enzyme cyclo-oxygenase (COX) and hence prostaglandin (PG) production. Following trauma/surgery, arachidonic acid is released from phospholipid bilayers in perturbed cell membranes by the activated enzyme phospholipase A2. COX enzyme then catalyses the formation of prostaglandins and thromboxane from arachidonic acid in the arachidonic pathway (Figure 2). Prostaglandins are involved in inflammation, nociception and fever modulation (prostaglandin E2 in the hypothalamus). These peripheral events are followed by a cascade of events in the spinal cord within the set pain pathways associated with inflammatory pain involving specific transmitters, receptors and mediators (Figure 3).31

NSAIDs are the gold standard analgesics in dentistry as acute post-operative dental pain is inflammatory in nature. Hence, they are superior to opioids.32 Ibuprofen 200/400 mg or diclofenac 25/50 mg, three times daily, are commonly prescribed NSAIDs.

NSAIDS are broadly classified as non-selective cyclo-oxygenase (COX) 1, 2 enzyme inhibitors (ibuprofen, diclofenac, aspirin) or selective COX-2 enzyme inhibitors (celecoxib, rofecoxib). The non-selective group is further subdivided based on its derivative compounds.

NSAIDs are contra-indicated for patients who have a history of gastro-intestinal (GI) ulcer/erosions, anticoagulant therapy/bleeding disorders, nephropathy, or intolerance/allergy to such drugs. If NSAIDs are contra-indicated, paracetamol may be used as an alternative (Table 4).

| Drug | Side-effects (SEs) | Mechanism of SE | Contra-indications | Interactions | Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSAIDs (eg ibuprofen 400 mg, diclofenac 50 mg) | GI bleeding | Erosion of stomach & intestine due to reduced production of protective mucous lining stimulated by PG. Systemic & direct mucosal contact effect | History gastric ulcer/gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) | Anticoagulants (warfarin, clopidogrel), SSRIs | Paracetamol opioids |

| Prolonged bleeding | Reduced thromboxane A2 reduces platelet aggregation | Patients with bleeding disorders or on anticoagulant therapy, especially the elderly, have increased risk of severe GI bleed | Anticoagulant therapy (warfarin, clopidogrel) can increase INR | Paracetamol opioids | |

| Nephrotoxicity | Reduced renal function due to reduced PG production which is necessary for renal perfusion | Patients with compromised renal function | Paracetamol opioids | ||

| Aspirin/NSAID intolerance or allergy | Inhibition of COX shunts arachidonic pathway toward leukotriene synthesis – signs and symptoms allergic response eg bronchospasm & anaphylaxis | Individuals sensitive to subtle elevation in leukotrienes – usually asthmatics Patients allergic to NSAIDs | Paracetamol opioids | ||

| PGs maintain patency of the ductus arteriosus during foetal development, especially 3rd trimester – avoid in pregnancy | Paracetamol | ||||

| Lithium and methotrexate serum levels elevated during concurrent NSAID use | Paracetamol opioids | ||||

| Paracetamol | Liver & kidney damage when taken at higher than recommended doses | Overdose – can result in hepatotoxicity | Hepatic impairment chronic alcoholism | Increased INR may occur in patients taking warfarin | Check with patient's physician |

| Opioids | Commonly nausea, vomiting, drowsiness & constipation |

Binding to specific opioid receptors in CNS and GI tract | Patients already on sedative and hypnotic medication (eg benzodiazepines, barbiturates) |

SSRIs, SNRIs-NERI, 5-HT-serotonin; TCAs, MAOIs* | Non-opioid analgesics alone or in combination with opioids reduce dose-related SEs |

Abbreviations: PG, prostaglandins; SSRIs, selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors; SNRIs, selective serotonin; NERI, norepinephrine re-uptake inhibitors; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants; MAOIs, monoamine oxidase inhibitors.

Pre-operative/preventive use of NSAIDs has been demonstrated to decrease the intensity of post-operative pain and swelling.25,33 During surgery, the synthesis of prostaglandins at the surgical site will transmit nociceptive impulses and sensitize the nervous system to the pain. Administering NSAIDs before surgery will inhibit prostaglandin synthesis and reduce the post-operative pain experience once the local anaesthesia wears off. Optimum serum levels of NSAID should be established whilst the tissue remains anaesthetized for maximum benefit.32 Pre-operative ibuprofen has been shown to be more effective at reducing acute post-operative pain than paracetamol or paracetamol with codeine, although the paracetamol was at suboptimal dose of 600 mg (as opposed to 1 g).33

Paracetamol is one of the most popular and widely used drugs for first-line treatment of fever and pain.34 Paracetamol does not demonstrate significant anti-inflammatory properties, implying a mode of action that differs from that of NSAIDs.29 Paracetamol is commonly prescribed as 1 g, four times daily. Overdose of paracetamol can cause hepatotoxicity and death from liver failure, so clear instructions on dose and timing should be given to patients.35

Although the efficacy of paracetamol is well established, its mode of action is still poorly understood. Paracetamol's significant anti-pyrexial activity suggests that the drug acts centrally. The following five mechanisms have been suggested:

A recent study at King's College London demonstrated, in the rat, that spinal pain receptors TRPA1 have a crucial role in the antinociceptive effects of paracetamol.37 Peripheral TRPA1 nociceptors did not demonstrate the same involvement.37 Paracetamol is a safe drug, which is well tolerated, with minimal side-effects. It is metabolized by the liver and is hepatotoxic. Hence caution is required in its use in chronic alcoholic patients and those with liver damage (Table 4). A Cochrane review, in 2007, of RCTs demonstrated that paracetamol is an effective drug to use for post-operative pain following oral surgery, with very few adverse effects.38

Opioids bind to specific opioid receptors in the central nervous system (CNS), causing reduced pain perception and reaction to pain and increased pain tolerance. In addition to these desirable analgesic effects, binding to receptors in the CNS may cause adverse events, such as drowsiness and respiratory depression. Moreover, binding to receptors elsewhere in the body (primarily the GI tract) commonly causes nausea, vomiting and constipation. In an effort to reduce the amount of opioid required for pain relief, and so reduce undesirable side-effects, opioids are commonly combined with non-opioid analgesics. On this basis, the opioid group of medication is not the first choice for management of mild to moderate acute orofacial pain.

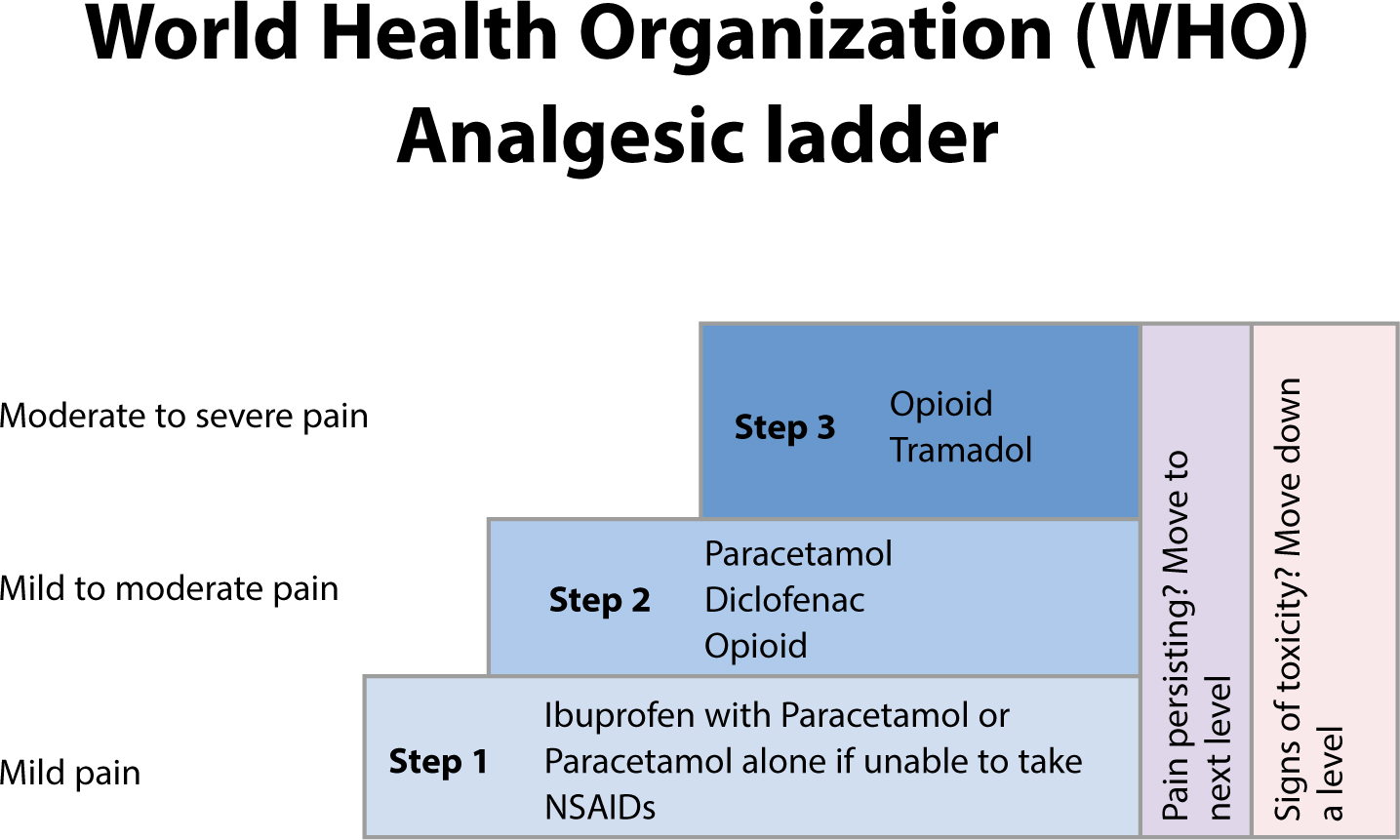

An analgesic ladder, for differing pain severity, was introduced by the World Health Organization in 1986 to assist analgesic prescribing by clinicians (Figure 4). Non-opioid analgesics (paracetamol and NSAIDs) form the basis of managing mild pain with introduction of opioid analgesia if the pain worsens.39 This principle of multi-modal analgesia highlights that the gold standard of pain management is by combinations of drugs, thereby maximizing analgesic efficacy at lower doses and minimizing side-effects. It also advocates regular administration of analgesics (every 4 to 6 hours) rather than ‘on demand’.39

NSAIDs should be combined with paracetamol, when possible, as they provide greater analgesia than when used alone,36 reducing the effective dose and, hence, possible side-effects. This synergistic effect is attributed to different sites of action of the two analgesics.32 Oral non-steroidal drugs often supplement the initial prescription of paracetamol. The latter is used pro re nata (PRN – when necessary) as the pain decreases. Taking paracetamol with NSAIDs only when necessary can limit potential side-effects of the NSAID.

Table 5 shows the authors' suggested analgesic regimen for acute trigeminal pain.

| Recommended | Alternative | |

|---|---|---|

|

Mild pain

|

Ibuprofen 200/400 mg TDS |

Paracetamol 1g QDS |

|

Moderate pain

|

Ibuprofen 400/600 mg TDS + paracetamol 1 g QDS |

Paracetamol 1 g QDS + codeine 30 mg QDS |

|

Severe pain

|

Ibuprofen 200/400 mg QDS + Paracetamol 1 g QDS + codeine 30 mg |

Paracetamol 1 g QDS + codeine 60 mg QDS |

Abbreviations: TDS, 3 times/day; QDS, 4 times/day; PRN, as needed

Odontogenic pain refers to pain initiating from the teeth or their supporting structures, the mucosa, gingivae, maxilla, mandible or periodontal membrane.

Orofacial pain can be associated with pathological conditions or disorders related to somatic and neurological structures. There are a wide range of causes of acute orofacial pain conditions, the most common being dental pain. Toothache can be very difficult to diagnose and may refer to pain initiating from the pulp, peri-radicular tissues or non-odontogenic sources. Diagnosis and management by dental practitioners is by thorough pain history-taking, dental clinical examination, and radiographs.

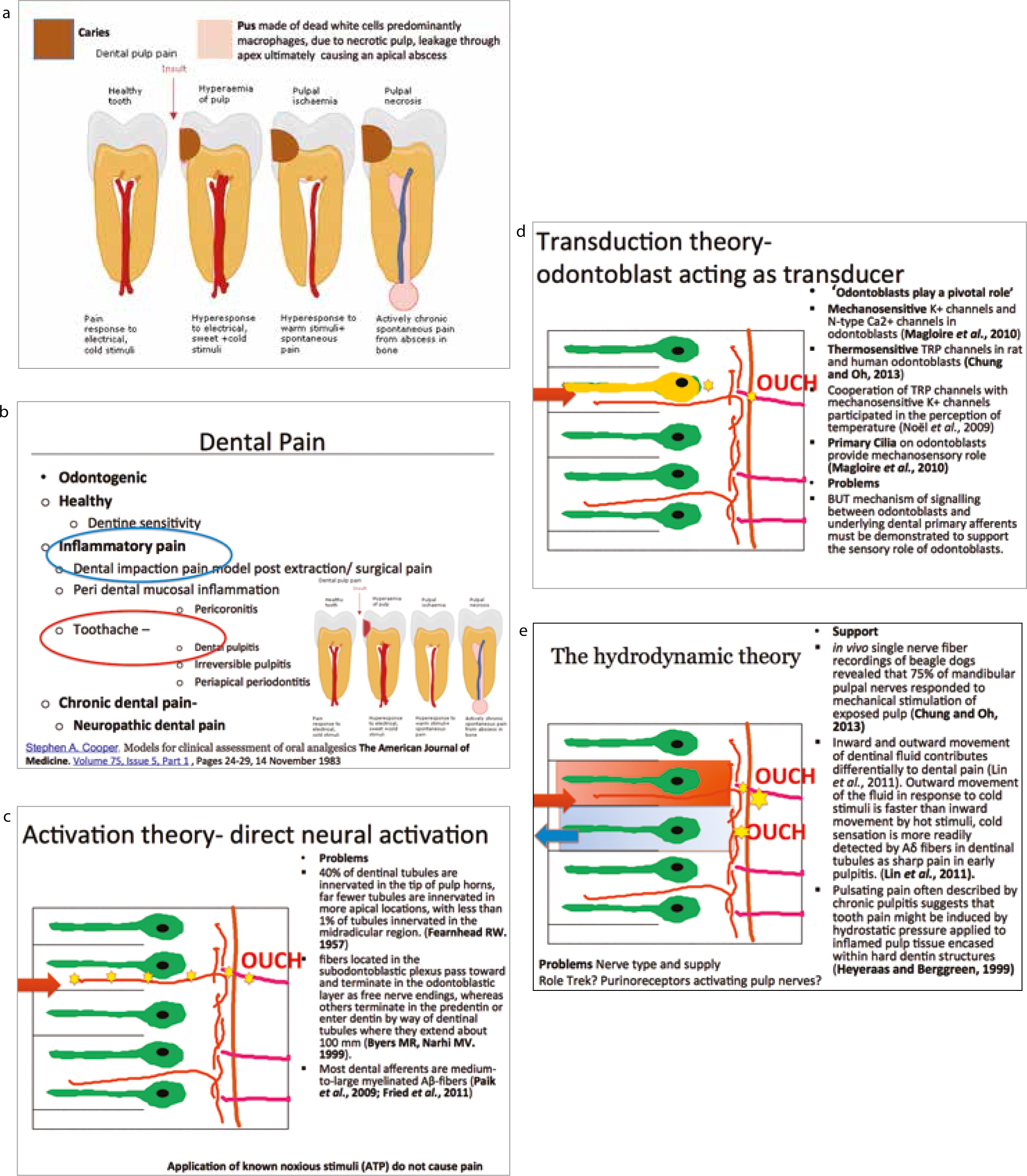

Toothache (see below) is caused by inflammation of the dental pulp (Figure 5) as a result of dental caries, the most common human infective disease worldwide.40 Interestingly, periodontal disease (gum disease), the second most common infection, is painless similar to other chronic mycobacteria infections, eg leprosy. Dentofacial pain is a common presentation in general practice:

A cross-sectional survey reported that a third of Brazilian schoolchildren reported toothache over a 6-month period. The major predictor of the prevalence and severity of pain was pattern of dental attendance (p<0.001).41

In healthy teeth, pain is often due to dentine sensitivity on cold, sweet or physical stimulus. Dental pulpitis may be due to infection from dental caries close to the pulp, inflammation caused by chemical or thermal insult subsequent to dental treatment, and may be reversible or non-reversible. Intermittent sharp, shooting pains are also symptomatic of trigeminal neuralgia, so care must be taken not to label toothache mistakenly as neuralgia. Confirmation of the type of pulpitis is a clinical diagnosis.

If the insult persists, the pulpitis will become irreversible with increased pulpal vascularity and resultant pressure, inducing ischaemia and causing sensitivity to heat with prolonged pain. Once necrosis of the dental pulp has occurred, the infection spreads through the apex of the tooth into the surrounding bone and periodontal membrane, initiating periodontal inflammation and eventually a dental abscess causing spontaneous long-lasting pain on biting on the tooth. Typically, the pain associated with an abscess is described as spontaneous aching or throbbing and, if associated with swelling in the jaw, trismus or lymphadenopathy, it may be indicative of an acute spreading infection. Thus different stages of infection have different clinical presentations (Figure 5).

Protection of the pulp to bacterial infection and chemical irritation by dietary and salivary content must be undertaken promptly to minimize persistence of acute pulpitis, thus evolving into chronic irreversible pulpitis. This treatment will involve a filling or restoration, which will resolve reversible pulpitis. Irreversible pulpitis may be managed in acute episodes by pulpal extirpation, tooth extraction with analgesia using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) if required. Routine prescription of antibiotics is unacceptable for the management of acute dental pain and should be solely reserved where local causal removal (pulp extirpation or extraction or inadequate pus drainage) has failed OR the patient presents with a spreading infection that cannot be immediately dealt with and requires referral to secondary care. Antibiotic prescription should comply with The Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP).42

There is tooth sensitivity from cold fluids and/or air, a reflection of a healthy pulp. With gingival recession, recent scaling, or toothwear due to a high acid diet or gastric reflux, there may be generalized dentine sensitivity. Management is summarized in Table 6.

| History | Special investigations | Management | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dentine sensitivity | Short, sharp pain on stimulation No lingering pain | Clinical exam exposed dentine |

Prevention of cause (eg brushing) |

| Reversible pulpitis | Pain on stimulation Short, sharp duration | Sensitivity tests (EPT/Endofrost/heat) |

Replacement restoration +/- lining |

| Irreversible pulpitis | Pain on stimulation but also may be spontaneous |

Sensitivity tests |

Root canal restoration/pulpotomy/extraction |

| Acute apical periodontitis (AAP) | May have pulpal symptoms previously |

Sensitivity tests negative response |

Occlusal adjustment/root canal treatment/extraction |

| Acute exacerbation of chronic apical periodontitis | May have history of pulpal symptoms and AAP in the past |

Radiography | Root canal treatment/extraction |

| Acute periapical abscess | Tenderness on percussion/palpation of tooth/mucosa |

Sensitivity tests |

Root canal restoration/extraction |

| Pericoronitis | Aching, localized swelling, +/- facial swelling, trismus | Sectional DPT |

Irrigation saline +/- +/- metronidazole 3 days |

| Alveolar osteitis | Worsening pain 3/7 post-extraction, halitosis | Irrigation saline +/-chlorhexidine alvogyl | |

| Cracked tooth | Pain on biting/releasing – short duration |

Bite on firm object – toothsleuth |

Cuspal coverage/Root canal treatment/extraction |

| Premature contact | Pain on biting | Articulating paper – check for heavy contact – eg recent tooth restoration | Adjustment/replacement of restorations |

| Maxillary sinusitis | Rhinorrhoea, congestion, headache, pain on leaning forwards/over sinus, dental pain | CBCT if unresponsive to treatment | Antibiotics only if persistent > 1 week or if very severe pyrexia |

| Temporomandibular joint disorder | Aching jaw joint, around ear – continuous/on chewing/opening wide |

Tenderness muscles of mastication |

Analgesics – ibuprofen/paracetamol |

Abbreviations: PDL – periodontal ligament; EPT – electrical pulp test; TTP – tender to percussion

This can be caused by infection spreading through the apical foramen of the tooth into the apical periodontal region causing inflammation (apical periodontitis) and ultimately a dental abscess if left untreated. Iatrogenic apical pain may result after dental treatment including premature contact if a restoration is left high in occlusion. This is characterized by an initial sharp pain, which becomes duller after a period. The pain is due to a recent tooth restoration that is ‘high’ compared with the normal occlusion when biting together and will persist until the height is reduced. Apical pain may also be induced post-endodontic treatment. This is severe aching pain following endodontic treatment such as root canal therapy or apicectomy and should be managed with analgesia similar to pulpitis; antibiotics are not recommended. While the majority of patients improve over time (weeks), a few will develop a chronic neuropathic pain state (see section on persistent post-surgical trigeminal pain).

This is either root canal therapy with removal of the necrotic pulp or tooth extraction. Periapical inflammation can lead to a cellulitis of the face characterized by a rapid spread of bacteria and their breakdown products into the surrounding tissues causing extensive oedema and pain. If systemic signs of infection are present, for example fever and malaise, as well as swelling and possibly trismus (limitation of mouth opening), this is a surgical emergency. Antibiotic treatment alone is not suitable or drecommended. If pus is present, it needs to be drained, the cause eliminated, and host defences augmented with antibiotics. The microbial spectrum is mainly gram positive, including anaerobes. Appropriate antibiotics are metronidazole with or without amoxycillin. Other antibiotics, including Augmentin, erythromycin and penicillin, are not recommended for dental infections. Antibiotic prescription should comply with The Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP).42 Antibiotics may be prescribed if the infection persists after endodontic therapy or dental extraction or adequate drainage of pus was not possible. Metronidazole (200 mg TDS PO 3 days) and/or amoxycillin (250 mg QDS PO 3 days) are the antibiotics of choice with review at 3 days. The analgesics of choice for dental inflammatory pain are ibuprofen (4-600 mg Soluble QDS PO PRN) combined simultaneously with paracetamol (acetaminophen 500–1000 mg QDS PO PRN). Table 4 provides more information about contra-indications and side-effects of these medications.

Pain commonly arises from the supporting gingivae and mucosa when infection arises from bacterial infection around an erupting tooth (teething or pericoronitis). Along with caries, it is one of the most common causes for the removal of third molar teeth (wisdom teeth).43 The pain may be constant or intermittent, but is often aggravated when biting down with opposing maxillary teeth. Where possible, extraction is always preferable to medication. If the infection is acute and spreading and extraction is not possible immediately then antibiotics may be prescribed. Management is summarized in Table 6.

Chronic periodontitis with gradual bone loss rarely causes pain and patients may be unaware of the disorder until tooth mobility is evident. There is quite often bleeding from the gums and sometimes an unpleasant taste. This is usually a generalized condition, however, deep pocketing with extreme bone loss can occur around isolated teeth. Food impaction interproximally, caused by an overhang of a restoration or poor interproximal tooth contact, can cause localized gingival inflammation and pain. Aggressive periodontal disease requires removal of local and systemic contributory factors, where possible, and adjunctive periodontal deep cleaning and scaling. Antibiotics are not indicated for periodontal disease management. Antibiotic prescription should comply with The Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP).42

This is a common complication after extraction, especially mandibular third molars44 with a reported incidence ranging from 0.5 to 5% in routine extractions to 1 to 37.5% in lower third molar extractions.45 It is defined as ‘postoperative pain inside and around the extraction site, which increases in severity at any time between the first and third day after the extraction, accompanied by a partial or total disintegrated blood clot within the alveolar socket with or without halitosis’.46 The pain is likely to be caused by irritation of the nerve endings in the exposed bone by necrotic food and debris trapped in the socket. Patients should be routinely warned of a possible dry socket prior to teeth extractions.47 Irrigation of the socket (avoid chlorhexidine containing irrigates due to recent reports of anaphylaxis) and placement of a sedative dressing (Alvogyl) is the treatment of choice. Management is summarized in Table 6.

This is a rapidly progressive infection of the gingival tissues that causes ulceration of the interdental gingival papillae.48 It can lead to extensive destruction. Young to middle-aged people with reduced resistance to infection are commonly affected (diabetes, HIV infection, chemotherapy). Males are more likely to be affected than females, with stress, smoking and poor oral hygiene being the predisposing factors. Halitosis, spontaneous gingival bleeding, and a ‘punched-out’ appearance of the interdental papillae are all important signs.49 Patients mainly complain of severe gingival tenderness with pain on eating and toothbrushing. The pain is dull, deep-seated and constant. The gums can bleed spontaneously and there is also an unpleasant taste in the mouth and obvious halitosis. Oral hygiene instruction, debridement, hydrogen peroxide and metronidazole are the treatment regimen of choice. Antibiotic prescription should comply with The Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP).42 The analgesics of choice for dental inflammatory pain are ibuprofen (400–600 mg soluble 3-4 times daily) combined simultaneously with paracetamol (500-1000 mg 4 times daily).50Table 4 provides more information about contra-indications and side-effects of these medications.

This can be caused by inflammation due to infection, trauma or tumours. Commonly involved regions include the sinuses, salivary gland, ears, eyes, throat, temporomandibular joint (covered in Part 6 of this series), or bone pathology.

Maxillary sinusitis often ‘mimics’ odontogenic pain and symptoms of pain forming inflammatory sinus disease, usually occur one week following an upper respiratory tract infection.51 The pain may be localized over the sinuses or it may mimic toothache in the maxillary posterior teeth. The pain tends to be increased on lying down or bending over. There is often a feeling of ‘fullness’ on the affected side. Acute sinusitis is usually viral in origin with treatment focused on relief of symptoms by using topical decongestants (<7 days) and saline irrigation, which help sinus drainage.51 If the patient is systemically unwell, feverish or there is evidence of spread of infection beyond the sinuses, then antibiotics should be prescribed.51 Referral to an ENT or otorhinolaryngologist specialist for endoscopic sinus surgery may be indicated in chronic cases.51 Routine prescription of antibiotics is unacceptable for the management of acute sinusitis. If persistent and appropriately confirmed by examination, necessary antibiotic prescription should comply with The Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP).42

The most common viral infections include herpes simplex Types I and II and herpes zoster. Antiviral prescription for these cases should comply with The Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP).42

Persistent pain may also involve neuropathic or neurovascular components, thus knowledge of the complexity of pain and local anatomy are crucial. This will enable the practitioner to diagnose and treat odontogenic causes, whilst simultaneously excluding sinister causes of pain requiring urgent management or neuropathic pain in which patients will not benefit from surgical or dental treatment.

Acute trigeminal pain is commonplace in the dental setting. Thorough history-taking and special tests can accurately diagnose acute pain and allow subsequent management. Perioperative pain can often be well controlled using affective local anaesthesia, with or without anxiolytic, thereby negating the use of general anaesthesia. Preventive ibuprofen may be beneficial if administered before the local anaesthetic wears off. Post-operative pain management is ideally controlled with combinations of non-opioid analgesics, namely ibuprofen/diclofenac and paracetamol, for superior analgesia and limited side-effects. The clinician must be cautious in only prescribing antibiotics when absolutely indicated to prevent development of antibiotic resistance and development of sepsis in the general population. In addition, the clinician should always be knowledgeable about what medications the patients are already prescribed and with which they're self-medicating. Abuse of ‘over-the-counter’ (OTC) analgesics is rife and paracetamol-related deaths are steadily increasing with analgesic abuse.