Abstract

We report a case of a mandibular arteriovenous malformation in a 3-year-old child, who attended our department, and have carried out a literature review.

From Volume 44, Issue 5, May 2017 | Pages 444-446

We report a case of a mandibular arteriovenous malformation in a 3-year-old child, who attended our department, and have carried out a literature review.

A 3-year-old Caucasian female presented to the Maxillofacial Department with a three-week history of swelling of the left cheek. On examination there was a bony hard swelling buccal to the lower left second primary molar (LLE) with inflamed gingiva. The mother reported occasional bleeding gums in the lower left quadrant for one year but had routine dental examinations.

An orthopantomogram (OPG) (Figure 1) showed three discrete radiolucent areas in the left mandible. On examination under anaesthesia there was no evidence of a vascular blush in the oral mucosa. Enucleation of the possible cyst was attempted and, on entering the cavity, bright red arterial bleeding was encountered, resulting in a loss of 150 ml of blood. The haemorrhage was arrested by packing the cavity with Surgicel® and the patient was haemodynamically stable. This raised the suspicion of AVM of the mandible.

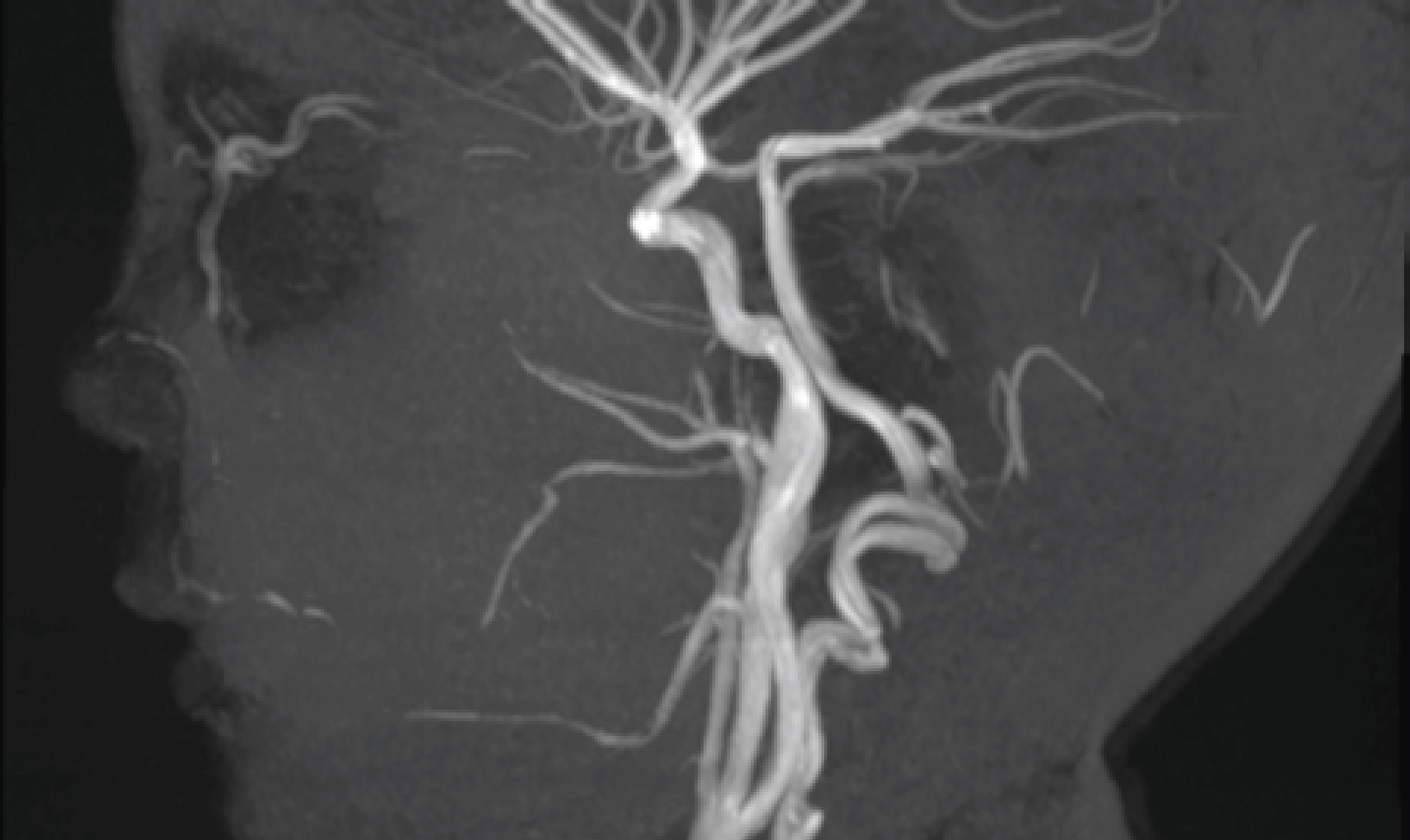

The patient had a catheter angiogram (Figures 2 and 3) and embolization (Figure 4). Onyx, a liquid embolic agent, was injected and the inferior dental artery was selectively embolized. At the termination of the procedure, filling of the arteriovenous malformation was no longer visualized. The patient was discharged but presented with a couple of episodes of minor bleeding from the surgical site, which settled down with tranexamic acid mouthwash. A post-operative MRI scan was taken after three months showing successful embolization of the AVM (Figure 5).

According to Mulliken and Young, two types of vascular lesions can be identified, depending on the intrinsic properties of the endovascular cells: haemangiomas and vascular malformations.1 Haemangiomas exhibit endothelial hyperplasia and enlarge by cellular proliferation. Clinically, haemangiomas usually appear in early infancy, grow quickly during the first months of life and then gradually involute over 5 or 6 years.2 Contrary to the abnormal proliferation of endothelial cells in a haemangioma, arteriovenous malformations show progressive ectasia of abnormal vessels, lined by flat endothelium. Advances in immunohistochemistry with the use of erythrocyte-type glucose transporter protein 1 (GLUT-1) have made it possible to characterize more accurately between haemangiomas and arteriovenous malformations.3 Haemangiomas consistently express GLUT-1 immunoreactivity (95% sensitivity, 100% specificity), whereas vascular malformations consistently fail to express GLUT-1 (100% sensitivity, 100% specificity).

Arteriovenous malformations represent anomalous blood vessels, where the walls of the arteries and veins directly interconnect via multiple abnormal vascular routes.4 They are caused by a disturbance in the latter stages of angiogenesis and persist during embryonic life.5 AVMs usually present as developmental anomalies from birth and develop in proportion to physical growth. The AVM grows asymptomatically at an early age and is promoted by local haemodynamic factors. There is a vicious cycle where blood shunted to the malformation causes growth of the lesion, which in turn causes increased shunting of the blood. Infections, trauma, vasomotor disturbances and hormonal imbalances lead to the overgrowth of the AVM.6

AVMs are rare lesions, with vascular lesions of the jaws having an overall 2:1 female:male occurrence, with peak incidence in the second decade. Despite being rare, 50% of all intraosseous AVMs occur in the maxillofacial region7 and a small percentage of these occur in the jaws. Vascular lesions are twice as common in the mandible as in the maxilla.8 Mandibular AVMs usually appear during adolescence, with extremes at 3 months and 74 years of age.9 In our case, the female child was 3 years of age.

AVMs can be life-threatening if left untreated due to severe blood loss as a result of biopsy or extraction.10 In most cases, exsanguination is the result of dental extractions, where the dentist has not been aware of the presence of an arteriovenous malformation.8

These lesions can present with a variety of clinical manifestations, depending on the severity of the malformation, and can go unrecognized for years. Occasionally, asymptomatic cases have also been reported.11 However, patients with AVM often present with soft tissue swelling (as was the case with our patient), paraesthesia, pain of variable intensity, facial asymmetry, mobility and migration of teeth, discoloration of overlying skin and intra-oral mucosal surfaces, local pulsation, noticeable bruit, bone resorption with palpable thrill, as well as resorption of the roots in the affected area with no evident tooth-related pathology and erythematous gingiva and bleeding pericoronal.12 Gingival bleeding seems to be a symptom common to most documented cases13 and the dentist in this case thought it was due to gingivitis. Systemic findings, such as blurred vision, paraesthesia, epistaxis and cardiac abnormalities, have been reported.14

Radiographically, there are no features on a panoramic radiograph to distinguish an AVM.15 They most commonly appear as multilocular radiolucencies and can have honeycomb or soap bubble appearance and can be interpreted as ameloblastic fibromas, ameloblastomas, odontogenic keratocysts, giant cell granulomas or malignant primary or metastatic tumours.4

Therefore, other radiographic aids, such as CT scan, MRI and arteriography, are indicated. CT scanning helps verify the extent of the lesion, bone erosion and the involvement of major vessels.16 Super-selective arteriography remains an essential tool in identifying the AVM and contributory vessels.17 It can provide significant information on the feeder arteries, draining vein, flow rate and collateral flow of the AVM.

There are numerous treatment options for arteriovenous malformations in varying combinations and degrees of success. These include ligation,18 embolization,19 as in this case, radical resection, use of sclerosing solutions,20 curettage and packing,21 radiation,22 bone wax packing in cavities followed by curettage and cryosurgery.23

This case highlights the importance of the GDP in being aware of the presence of AVMs and other vascular lesions that may arise in the mandible. This is especially true where there is gingival bleeding and oral hygiene is good, ie signs and symptoms do not correlate with clinical findings. If the GDP had extracted the tooth in practice, the bleeding could have been uncontrollable and would have been an extremely difficult scenario to manage in the primary setting. The treatment of AVMs requires a multidisciplinary team approach from anaesthetists, neuroradiologists and maxillofacial surgeons.